Sustainable finance has gone through a spectacular growth trajectory over the past decade – its adoption as a standard practice by most major asset managers and banks has served to perpetuate this boom as a transformative force in the financial sector.

While tremendous progress has undoubtedly been made, major gaps still exist in financing a global transition to a sustainable development pathway. What barriers remain, and how can these be addressed?

From an obscure niche market over a decade ago, sustainable or ‘green’ finance has grown tremendously in recent years. Valued at USD$30.7 trillion as of early 2018, global sustainable investment had approached the combined GDP volume of China and the EU.

Spurred by rising consumer demand, alongside external pressure by civil groups and public institutions, ESG functions (functions that stress the importance of environmental, social and government factors) have proliferated across the financial sector to provide a more holistic assessment of loans and investments, especially in pension funds which are averse to reputational risks.

These efforts are occasionally criticized for their alleged inadequacy, evidenced recently in TCI’s (an investment management firm) allegations of BlackRock’s ‘greenwashing’ for not leveraging its public equity investments to prompt greenhouse gas emissions disclosures. Despite present shortcomings, several major asset managers are setting ambitious goals for the near future. Schroders has committed to full ESG investment integration by 2020, while BlackRock aims to double its offerings of sustainability-focused exchange-traded funds to 150, alongside increasing its sustainable assets 10-fold from USD$90 billion today to USD$1 trillion within 10 years.

Action is also taking place on the selling side of the industry, with bulge-bracket bank Goldman Sachs pledging USD$750 billion for climate transition projects in the coming decade, a sum exceeding the size of Switzerland’s economy today. Given the size and credibility of these financial institutions, the impact of these statements backed by tangible actions should not be underestimated, as they create strong signals that environmental sustainability will continue growing as a key focus in the years to come.

Without neglecting the benefits of these commitments, it is important to bear in mind that mitigating the detrimental effects of climate change is an inherently hefty expenditure, even before considering how to reverse it. A 2013 study by the World Economic Forum forecasted that mitigation in the Global South alone will incur expenses of more than US$600 billion annually, whilst stabilizing worldwide GHGs to 450ppm of CO2 necessitates annual green infrastructural investments of about USD$5.7 trillion.

RELATED ARTICLES: ‘Green’ Investing: The Future of Business? | The Innovation Springboard | How Honest is Green Finance? | Greenwashing in Finance

Fortunately, these grand challenges also generate opportunities for value-creation, with climate investments projected to open up about USD$23 trillion of opportunities in emerging markets alone. Despite commendable institutional progress made through the Green Climate Fund (GCF), even its target pledge of US$100 billion per year from 2020 falls short of addressing these financing needs, by orders of magnitude. Fiscal constraints inhibit the ability of governments to take on the sole responsibility in funding this transition to a more sustainable developmental pathway, necessitating the need for private sector involvement.

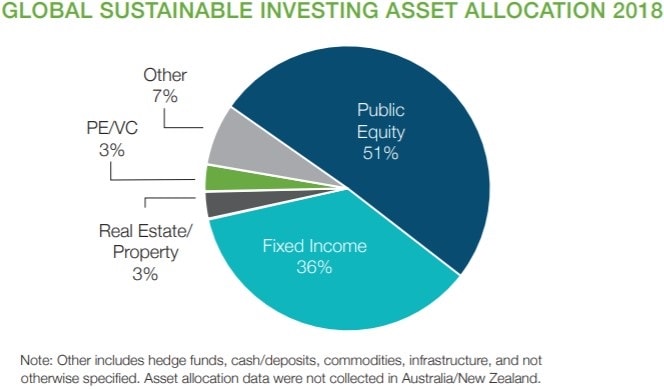

Whilst essential, an accelerating growth of sustainable finance alone would be insufficient in combating climate change without undertaking further structural changes. Even in the Global North, over half of sustainable investment assets take the form of public equities, with a far smaller proportion being directly allocated to infrastructural development- though the latter may grow to be increasingly lucrative with looming macroeconomic conditions of low-interest rates and reduced returns on stocks.

More vital, however, is to cease the provision of loans and services to environmentally destructive companies, which many major banks are still involved in. These banks frequently adopt contradictory policies; for instance, whilst Goldman Sachs recently became the first major American bank to cease direct financing for Arctic oil exploration alongside thermal coal mines and plants around the globe, this did not exclude other fossil fuel operations such as fracking and tar sands. Indeed, Goldman Sachs has been selected as one of the banks to lead the initial public offering (IPO) of state-owned oil giant Saudi Aramco, alongside its bulge-bracket counterparts of JPMorgan and Morgan Stanley.

In view of the present-day profitability and entrenched interests in favor of fossil fuels, it is unsurprising that global investment in renewable energy still lags far behind, with similar trends being observed in industries such as mining or chemicals. Ultimately, sustainable finance remains but a means to a greater end goal, which cannot be realized without extensive policy action.

This article has been posted on Earth.org as well. Click here to see it.

In the cover picture: The Bosco Verticale, in Milan; Italy. Photo Credit: Unsplash