Ending world hunger is a complicated goal. The conditions to reach it appear in the fully-worded United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 2: “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture.” Ending hunger means not only achieving food security — or the availability, access to and use of food — but also improving nutrition; calories alone aren’t enough. This can only occur through the promotion and adoption of sustainable agriculture in the form of a food production and delivery system that meets society’s needs in the present without compromising the needs of future generations. Sustainable agriculture embraces the environmental, economic and social conditions that challenge food security. By taking a whole systems approach, agriculture, when done sustainably, has the potential to relieve hunger and create lasting change.

How Big is World Hunger?

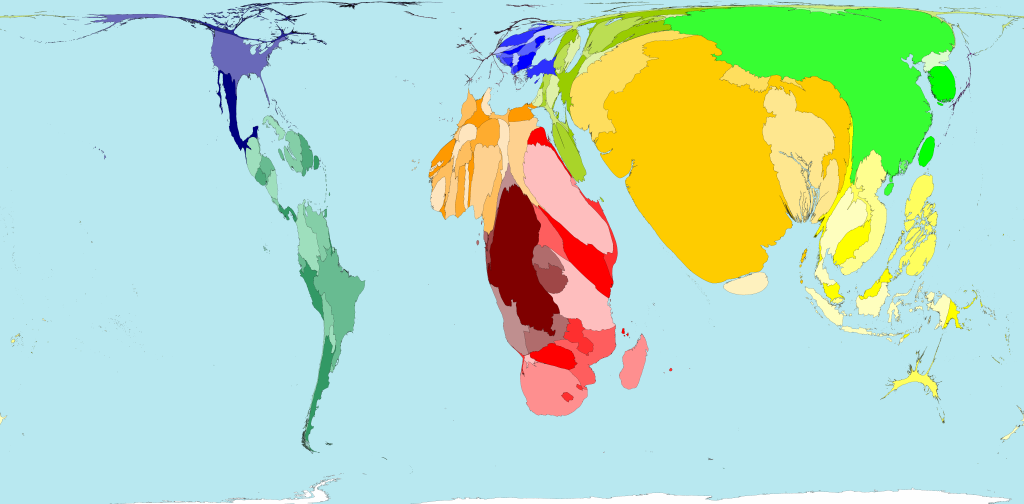

The current world population of 7.3 billion is expected to reach 9.7 billion in 2050. Today, nearly 800 million people, or one in nine, are undernourished. By 2050, that number could grow by two billion. Most of the world’s hungry live in developing countries, where 13 percent of people face undernourishment. Asia faces the greatest hunger burden, with two-thirds of its population suffering from undernourishment. In Sub-Saharan Africa, one in four people experience the same lack of food and vital nutrients.

Hunger and malnutrition hit the hardest among the most vulnerable population: children. In the first 1,000 days of life, from gestation to a child’s second birthday, malnourished children suffer irreparable loss in brain development. Poor nutrition causes nearly half of all deaths in children under five. It hurts their ability to learn and grow, as shown by the one in four children who experience stunting worldwide. In developing countries, that proportion can rise to one in three. In Africa, among the primary school-age children who manage to attend school, 66 million attend classes hungry.

In the Photo: A map showing rates of undernourishment in 2000 to scale. Photo Credit: WorldMapper.org / Sasi Group (University of Sheffield) and Mark Newman (University of Michigan)

Extreme hunger and malnutrition inhibit sustainable development and create a trap that cannot easily be escaped. Adults who suffer from undernourishment as children grow up facing lifelong health challenges and find themselves more prone to disease. They often struggle to earn a living or improve their agricultural productivity because of two main conditions: hunger and malnutrition. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture, which maximizes investment in agriculture that improves nutrition, holds the key to solving both. That means saying goodbye to agriculture that only supports homogenous diets of nutrient-poor, staple foods and welcoming more diverse diets. By growing, consuming and selling more diverse crops, especially during off seasons, farmers diversify their incomes, which allows them to buy and consume more nutritious food.

Progress in the Fight to End Hunger

Part of the Millennium Development Goal 1 – to halve the number of hungry people, or reduce it to below 5 percent, from 1990 to 2015 —made significant progress, despite major population growth. By 2015, when monitoring of the Millennium Development Goals ended, 72 of 129 countries reached the goal. Developing regions decreased their share of undernourished people from 23 to 13 percent, and the world now has 218 million fewer people suffering from undernourishment than it did 25 years ago.

Photo Credit: ACDI/VOCA

Much of that result has to do with agriculture. As the single largest employer in the world, agriculture provides livelihoods for 40 percent of today’s global population. It’s the largest source of income for poor, rural households. In fact, 500 million small farms provide up to 80 percent of the food consumed in a large part of the developing world. Most farmers’ fields are rain-fed, meaning their crops rely solely on rainfall. Without irrigation systems, they face serious risks due to unpredictable weather patterns. For this and many other reasons, investing in technology for smallholder farmers helps ensure food security for the poorest populations and consistent food production for local and global markets. Setting appropriate policy environments, catalyzing private investment to make markets more effective and making agricultural improvements sustainable together can help end world hunger.

The United States’ Collaborative Approach

Since 2010, the American government’s Feed the Future Program has shown that progress in combatting hunger and poverty is possible when governments jointly pursue a solution with the private sector. Its projects, which exist in 19 focus countries across Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, have created nearly 5,000 public-private partnerships and leveraged more than $600 million in private-sector investments in food systems.

- The program is unique in how it focuses efforts geographically and enlists partner governments to help set the appropriate policy environment. In Bangladesh, the government got involved with Feed the Future to increase opportunities for women to earn income through farming and entrepreneurial ventures.

- In Kenya, the government took over and scaled a livestock insurance program for pastoralists. It has paid out millions of dollars to over 12,000 households to help them endure climate shocks.

- So far, the program has helped the focus countries put over 100 policies into place to strengthen national food security.

Feed the Future projects insist on sustainable impact and performance monitoring. Already, hunger and poverty have declined by one-third in some project areas. According to the Feed the Future website, “Poor nutrition perpetuates the cycle of poverty and hunger, leading to poor health, lower levels of educational attainment, and reduced productivity and wages in adulthood… The good news is we’re making progress.” Last year, Feed the Future reached 18 million children globally with interventions designed to improve their nutrition.

Photo Credit: ACDI/VOCA

The program refuses to ignore the close, often causal, relationship between hunger, poverty, and agriculture. It makes an inclusive agricultural sector paramount. “Studies suggest that every 1 percent increase in agricultural income per capita reduces the number of people living in extreme poverty by between 0.6 and 1.8 percent,” the website states. Overall, Feed the Future strives to improve the incomes of women and men in rural areas who rely on agriculture for their livelihoods.

In Ghana and Zambia, ACDI/VOCA implemented Feed the Future projects that helped identify and train outgrower businesses. These businesses gave entrepreneurs the chance to not only sell needed inputs to local farmers, but also to coach them on best practices to improve their productivity. As points of aggregation, these same outgrower businesses bought and processed farmers’ yields and sold those yields in bulk to wholesalers, helping farmers and themselves earn more. This type of resilient agricultural growth asks market stakeholders to adopt new behaviors like farming smarter, losing less product in transit and marketing healthy, value-added food to consumers.

Photo Credit: Feed the Future

How Can We Adapt?

If ending hunger requires better food security and nutrition, the world should pursue nutrition-sensitive agriculture intensely. Organizations that implement agricultural development projects for the world’s donor community hold a unique and influential position. Many see a strong need for nutrition-sensitive agriculture, which addresses the underlying causes of malnutrition to create an enabling environment for quality nutrition to happen. ACDI/VOCA, an economic development nonprofit that connects farmers to markets, knows that Feed the Future’s approach tackles not only a lack of food, but also a lack of adequate nutrients.

Related Article: “FARMER REAPS THE BENEFIT OF EMBRACING CONSERVATION AGRICULTURE“

Every agricultural development project must develop its activities through the lens of nutrition. Filling bellies with more grain cannot be called a success if that grain is poisoned by mycotoxins, or if local diets still fall short of necessary micronutrients to create healthy families.

Efforts to grow agricultural productivity must focus on diversified, nutrient-rich crops, less post-harvest loss, and women’s empowerment. After all, women make up 43 percent of the world’s agricultural labor force.

Focusing Agricultural Development Projects

Markets play a critical role in whether both women and men have access to nutrient-rich foods. ACDI/VOCA’s recent Feed the Future projects in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania and Zambia have worked to improve smallholder farmers’ productivity and access to markets and trade. Without inclusive market systems, the availability of nutrient-rich foods is limited for poor farmers in remote areas. Organizations that implement agricultural development projects should take this into account, as they work to improve the access, availability, and use of quality, nutrient-rich foods for adults and children.

Photo Credit: ACDI/VOCA

What does it mean for a project to take a nutrition-sensitive approach? First, the approach should begin during the project’s design phase, not after implementation has begun. However, even existing agricultural projects can retool to become more nutrition-sensitive. Skilled technical staff can identify the types of activities that would likely increase the consumption of nutrient-rich foods among beneficiaries. An example could be helping women gain more control over household decision making, including the types of food bought. Or staff may focus on enabling more women to use labor-saving technology, or getting messages across to women and men about the importance of using increased incomes to buy more diverse foods. Projects may also look at how nutrient-rich food gets produced and retained by households for their own consumption. Measurable indicators like these will show if more equitable and diverse food consumption occurs among family members.

Photo Credit: ACDI/VOCA

The world has made incredible progress towards ending world hunger. But we still have a long way to go. Farming experts and other professionals who work to solve hunger continue to help Sustainable Development Goal 2 realize its ambitious future.

Today, the turning point in agriculture is sustainability. But how do we strengthen agricultural markets and food systems to boost economic progress and deliver on the promise of improved diets for all? The key lies with sustainable, nutrition-sensitive agriculture. When working so hard to produce more food, smallholder farmers should also be nourishing their families.

The key lies with sustainable, nutrition-sensitive agriculture.

ACDI/VOCA is an economic development organization that fosters broad-based economic growth, raises living standards, and creates vibrant communities. Based in Washington, D.C., ACDI/VOCA has worked in 146 countries since 1963. Its expertise is in catalyzing investment, climate smart agriculture, empowerment & resilience, institutional strengthening, and market systems.