Today UN member states formally adopt the Global Compact for Migration, which endorses “stopping allocation of public funding… to media outlets that systematically promote intolerance, xenophobia, racism and other forms of discrimination towards migrants”. Stop Funding Hate co-founder Richard Wilson tells the story of a growing global movement for ethical advertising.

In April 2015, Britain’s best-selling newspaper, the Sun, published an article by the columnist Katie Hopkins, likening African migrants to “cockroaches”.

In response, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, issued a blistering statement, condemning “decades of sustained and unrestrained anti-foreigner abuse, misinformation and distortion” by the UK press.

“History has shown us time and again the dangers of demonizing foreigners and minorities, and it is extraordinary and deeply shameful to see these types of tactics being used in a variety of countries, simply because racism and xenophobia are so easy to arouse in order to win votes or sell newspapers”.

These words struck a chord with many in Britain. Day after day, year after year, we had seen the newspaper front pages blaming migrants and refugees for all manner of ills – so much so that this had almost come to seem normal.

Sometimes it can take an outside observer to help us see how bad things have become. It was a real wake-up call to realize that Britain’s newspapers were now so extreme that they were being called out for “hate speech” by the United Nations.

But most shocking was the evidence that hate in the media was fueling real-life violence on our streets. This anti-migrant rhetoric reached fever-pitch in 2016, during Britain’s tumultuous EU referendum campaign. The aftermath saw a surge in anti-migrant hate crimes. Experts warned that these attacks had been “fueled and legitimized by politicians and by the media”.

IN THE PHOTO: Stop Funding Hate supporters. PHOTO CREDIT: Stop Funding Hate

IN THE PHOTO: Stop Funding Hate supporters. PHOTO CREDIT: Stop Funding Hate

At the time, I worked for a charity that took the main newspapers every day. Leafing through the Sun and Daily Mail, I was struck by how many of the companies I shopped with were advertising alongside stories that demonized migrants and other minorities.

But what if some companies could be persuaded to pull their ads? If enough advertisers walked away, could this help cancel out the financial incentives for printing hate?

I set up a Facebook discussion group to develop the idea. Soon hundreds had joined and the group took on a life of its own. A TV editor worked with us to make a video highlighting the core ideas behind the campaign. We set up a public Facebook page, and published the video one morning in August 2016.

Within a few hours the video had been shared on Facebook thousands of times. In days it had over 3 million views. We began receiving messages from people all across the UK who wanted to get involved. Many wrote of their frustration and sense of powerlessness at the levels of hate within the media – and the impact this was having on our society. Others had been concerned about these issues for a long time – but hadn’t realized how many others shared those worries until they saw the huge response to our campaign. Many talked about the extent to which they themselves had been affected by the climate of hatred fueled by elements of the UK press.

It seemed we had tapped into a groundswell of public concern that had existed for a long time without much of an outlet. But perhaps if enough us talked to the companies we shopped with about their advertising, we could have a practical impact.

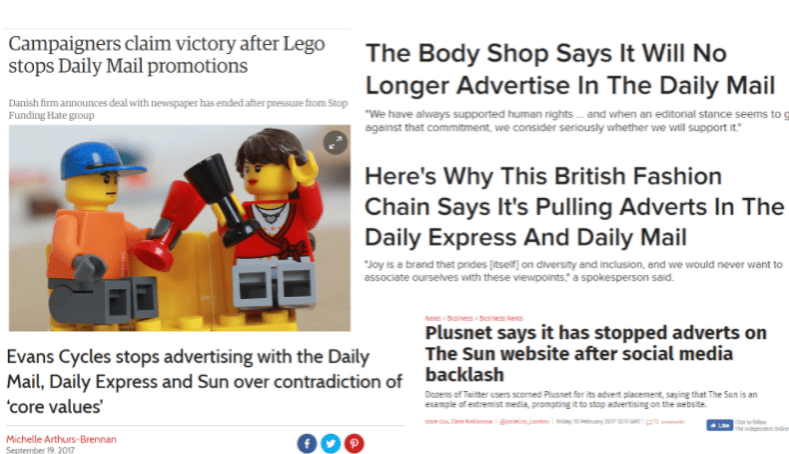

Stop Funding Hate’s big breakthrough came three months into the campaign. In November 2016, amid ongoing concern about the media’s behavior, a Stop Funding Hate supporter named Bob Jones wrote a heartfelt message on the Facebook page of Lego, one of the Daily Mail’s big promotional partners:

I love Lego. My 6 year old son loves Lego… But I’m concerned. For a few years now you have done free giveaways in the Daily Mail newspaper… lately their headlines have gone beyond offering a right wing opinion. Headlines that do nothing but create distrust of foreigners, blame immigrants for everything, and as of yesterday are now having a go at top judges in the U.K. for being gay while making a legal judgment…

Your links to the Daily Mail are wrong. And a company like yours shouldn’t be supporting them…

Bob’s message was shared across Facebook and Twitter by thousands of other Stop Funding Hate supporters. Days later, Lego replied with a one-sentence tweet:

We have finished the agreement with The Daily Mail and are not planning any future promotional activity with the newspaper.

Within minutes I was getting calls from journalists. That evening Stop Funding Hate’s co-founder Rosey Ellum was interviewed on primetime TV news. Lego’s single tweet triggered media headlines not just in the UK but across the globe.

And over the next few weeks, we noticed that something else was happening:

Similar campaigns were springing up in other countries. In Denmark, online activists using the hashtag #StopFundingHateDK persuaded advertisers to leave a controversial media outlet named Den Korte Avis. In Germany, the #KeinGeldFuerRechts campaign convinced big brands to pull their ads from the far-right website Breitbart. And in the United States, a campaign was launched named Sleeping Giants, which also targets Breitbart, and has since influenced over 4,000 online advertisers to withdraw their support.

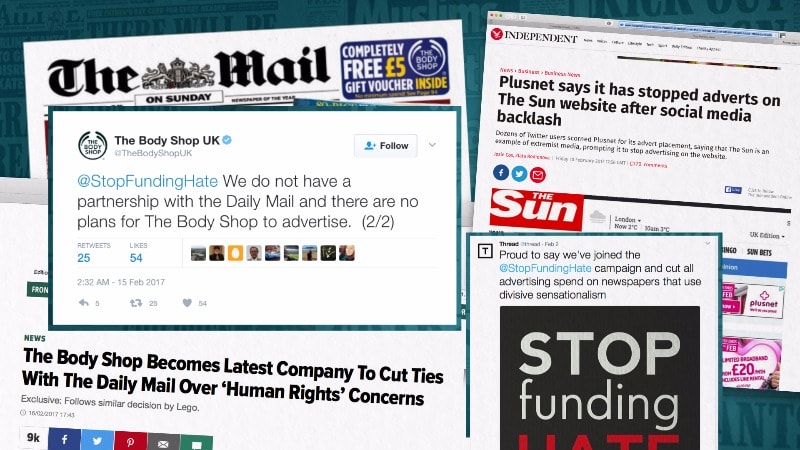

IN THE PHOTO: Stop Funding Hate success on Twitter. PHOTO CREDIT: Stop Funding Hate

One of the big insights of Sleeping Giants is that many companies don’t know their ads are appearing on Breitbart. Digital advertising typically involves brands buying from a large network (such as Google Adsense), who will distribute that company’s ads across thousands of different websites within its system. This has fueled a profusion of media outlets that use inflammatory stories to drive traffic, supported by advertisers who often have very little idea about what they are funding.

Unfortunately, extreme (and wildly inaccurate) messages tend to work well as clickbait. Thus internet advertising has helped incentivize a global proliferation of online hate speech, conspiracy theories, and “fake news”. And as print sales fall, and more advertising moves online, some traditional media have been publishing more extreme content in an effort to keep up.

But the internet also makes it easier than ever to organize together, and use our power as consumers to do something about this problem. And there is growing pressure on advertisers to tackle it at source.

IN THE PHOTO: More from Stop Funding Hate campaign. PHOTO CREDIT: Stop Funding Hate.

In May last year, Stop Funding Hate was invited to address a meeting of UN member states developing a new Global Compact for Migration. We’d been asked to propose tactics for pushing back against the global rise in xenophobia. Our argument was simple:

We need to reach a critical mass of big companies who will publicly commit to advertising ethically – to make it part of their corporate social responsibility policy that they will not advertise in publications that incite hatred.

UN Member States can lead by example by publicly committing to the principle of ethical advertising – and ensuring that any government advertising campaigns are not channeled through media that have a track record of inciting hatred.

In August we learned that this principle had made it into the final text of the agreement. The UN Global Compact for Migration endorses a range of measures for “promoting evidence-based public discourse” on migration, including “investing in ethical reporting standards and advertising, and stopping allocation of public funding or material support to media outlets that systematically promote intolerance, xenophobia, racism and other forms of discrimination towards migrants”.

This is just a first step, but it sets a hugely important precedent: For the first time, a major United Nations agreement has recognized that advertising is a global business ethics issue – and that ethical advertising could play a significant role in pushing back against the rise of xenophobia.

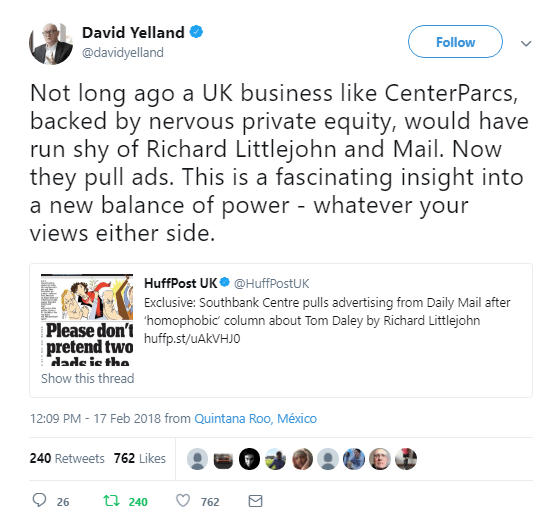

In the UK, 2018 has seen a marked reduction in the number of anti-migrant front pages. Earlier this year, the Sun publicly apologized for its 2015 article comparing African migrants to cockroaches. The Daily Mail has changed its editor of 26 years and revealed plans to “detoxify”.

The Daily Express also has a new editor, who has promised to make changes, and admitted that the newspaper previously fueled “Islamophobic sentiment”.

There is still some way to go. But it seems clear that this campaigning model of consumer engagement with advertisers through social media offers a powerful new tool for challenging hate and pushing for improved press standards.

Appropriately enough, in recent weeks the UN Global Compact for Migration has itself been the subject of a global “fake news” campaign across both social media and the established press.

The extremists have good reason to be worried. Last year over $500 billion was spent on advertising worldwide. If governments begin applying more ethical checks to their advertising, and big companies follow suit, this could slash funding for xenophobic media outlets across the globe, and help turn the tide of hate and misinformation.