Perhaps one day our societies will allow us to simply “be.” Until then, navigating cultural identity as a second-generation American is overwhelmingly burdensome, especially with a Latin American background—one with which we sometimes find ourselves having to pick a single race. We learn one culture at home, but are taught another growing up in our American communities.

The United States Census Bureau defines “second-generation” as those with at least one foreign-born parent; yet the most perplexing question taunts us each time we meet someone new or visit a country outside of our own: “Where are you from?”

In the Photo: Defining the Immigration Generations Photo Credit: Pew Research Center

“Planet Earth,” is my usual response to this vague question. Although technically correct (yet not met with the comedic reaction I would expect), the specifics of this answer are much more complex.

Like many of our parents, my mother came to America to make sure her children will have better opportunities than she did growing up. The language barrier was something she always had issues with, but she figured that living in cities like New York City, Dallas and Miami wouldn’t require her to learn—nor speak—English full-time in order to be able to work and support her two children with my stepfather.

At home, our family is Dominican and so is everything that comes along with it. Sunday mornings would be filled with the aromas of scrambled eggs and fried salami, tostones (fried plantains) and queso frito (fried cheese). The sound of bachata would seep through the walls and into our neighbor’s home, and my mother would often open the door with curling rollers and a broom saying, “Perdon, perdon. I’m berry, berry sorry!” She always reminds me to be grateful that I was born in America, and that I didn’t have to go through the struggles that she did.

In the Photo: The Dominican Republic Photo Credit: Asael Peña

In the Photo: The Dominican Republic Photo Credit: Asael Peña

Although I wasn’t born in the Dominican Republic, I would feel ashamed to ignore my Dominican background. Not only am I lucky to speak Spanish fluently, but I appreciate the mix of races, too, and better understand the history of the Dominican Republic.

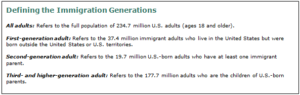

I am certainly not alone. The Pew Research Center has documented the percentage of the total US population that the first and second-generation Hispanics make up, dating back to the 1900s. Although the numbers have mostly trended downward, we see that they have been spiking since the 1990s.

In the Photo: Percentage of US population who are first and second-generation immigrants Photo Credit: 2000-2015 data and all second-generation data from Pew Research Center analysis of Current Population Surveys (IPUMS); historical trend from Passel and Cohn (2008) and Edmonston and Passel (1994).

In the Photo: Percentage of US population who are first and second-generation immigrants Photo Credit: 2000-2015 data and all second-generation data from Pew Research Center analysis of Current Population Surveys (IPUMS); historical trend from Passel and Cohn (2008) and Edmonston and Passel (1994).

In 2015, 11.9% of the U.S. population were second-generation Hispanic-Americans, over 38 million people in total. Regardless of what race or background, the feelings of cultural identity in the American society impact all second-generation Americans.

Roughly six-in-ten adults in the second-generation consider themselves to be a ‘typical American’

Moreover, Pew Research surveys of Hispanics and Asian Americans documented that “roughly six-in-ten adults in the second-generation consider themselves to be a ‘typical American’,” and that “most in the second generation also have a strong sense of identity with their ancestral roots.” In addition, “some 37% of second-generation Hispanics and 27% of second-generation Asian Americans say they most often describe themselves simply as ‘American’.” What’s more confusing here is defining the term “typical American.” A Californian may have differences in upbringing compared to a Kansan.

The Latin American Race Complex

Latin Americans aren’t the first immigrants to the United States and most certainly won’t be the last. What makes us unique is that we don’t necessarily always belong to one race, as each Latin American country is rich in its own culture. That’s why the following always seemed like the hardest question on most of my tests: “Select your race.”

I recall the options being something like:

- American Indian/Alaskan Native

- Asian

- Black/African-American

- Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

- White

In confusion, I always left this part blank. I simply did not know what race I was. My mother’s family is mostly white. Conversely, my father’s family is mostly black. At that time, the history of the Dominican Republic was not taught to me, and I had yet to learn about the indigenous Taíno tribe that inhabited the island before the 15th century colonization. My parents were too busy chasing the American dream that they forgot to teach me the history of their very own people.

From a young age, second-generation Latin Americans in the United States find it very difficult to fit in with our white, black, Asian, and other single-race American counterparts. We’re taught in grade school the many successes of white colonizers and the African slave trade. It isn’t until higher education, however, that we get to choose classes that teach us about our specific backgrounds. Until then, we’re basically led to believe that America is a country built by white colonizers and that it is their past agreements with Native Americans that make America the powerful white nation that it is today.

In reality, America is such an economic powerhouse partly because of suffering and free labor that African-Americans have endured for centuries. It is primarily a white nation not because of the agreements between white colonizers and Native Americans, but because of the massive genocides of indigenous American tribes. Learning the truth about American history has shed a little more light on cultural identity for second-generation Latin Americans in the United States.

Related Articles:

![]() INEQUALITY: A PERSONAL TAKE ON ECONOMIC INDICATORS

INEQUALITY: A PERSONAL TAKE ON ECONOMIC INDICATORS

by Anna Wilken

![]() SELECTIVE EMPATHY AND THE MEDIA’S RESPONSIBILITY TO ALL AMERICANS

SELECTIVE EMPATHY AND THE MEDIA’S RESPONSIBILITY TO ALL AMERICANS

by Latoya Dixon

![]() HOW AMERICA LOST WORLD LEADERSHIP

HOW AMERICA LOST WORLD LEADERSHIP

A Global Society

I recall special moments while backpacking Europe that prove just how globalized our societies are becoming. For instance, it didn’t take long for me to feel nostalgic after walking into my hostel in Paris, since the music coming from the speakers was an old merengue song that my parents used to dance to while growing up. I instantly picked up my phone to FaceTime my mother who was over 4,600 miles away in Florida.

My accommodation in Berlin was also playing bachata in the lobby—a welcoming surprise. I could never forget teaching my hostel-mates how to dance salsa in Venice once they, too, found out my background.

Not only am I proud to have Caribbean blood, I am also grateful to be able to easily travel abroad with an American passport.

Thanks to the internet and other technology, we’re able to learn about our own backgrounds and meet people from similar cultures without stepping a foot away from our home towns. Furthermore, people from all over the world are no longer in the dark when meeting people from remote places, like some of the smaller islands in the Caribbean. Airplanes and low-cost airlines have made it easier to visit the countries our parents migrated from, making us feel closer to home and family.

Despite the difficulties that come with being a second-generation American, the pros outweigh the cons. We have the possibility to travel the world with ease compared to other countries, and, from my experience, we are generally viewed as likeable and outgoing. It’s best to not let cultural identity get in the way of making new friends, regardless of what background we’re from. After all, the world will hopefully reach a point of allowing everyone to simply “be.”