For the five science fiction films I focus on here (“Ex Machina,” “Never Let Me Go,” “Moon,” “Sleep Dealer,” and “Children of Men”), these affective progressive films strikingly interrogate the self/other dynamic that is at the heart of our human history of exploitation, enslavement, wars, and other crimes against humanity. In short, as our history shows, othering other people (people of color, LGTBQ people, women, working class, alternative belief systems, etc.) — instead of seeing other people as our selfs — is a core contributing factor to dehumanizing people, which, in turn, invariably leads to heinous acts of degradation. As I show below, I contend that science fiction powerfully reveals this (self) destructive self/other dynamic, especially in terms of using clones and AI as a metaphor for others. (Note: Science fiction also interrogates this self/other divide via aliens, which I have touched on elsewhere. See my blurb on the science fiction/superhero film “Guardians of the Galaxy” for more.)

The Self/Other Divide: Science Fiction Films That Focus on AI, Cloning, “Third World” Labor, and Immigration

“Ex Machina” (2015, Alex Garland)

To my mind, “Ex Machina” is the most fascinating AI (artificial intelligence) film since “Blade Runner” (1980, Ridley Scott). And I also think it is a deeply progressive film as well. I can’t entirely work through the complexities here; suffice it to say that this science fiction film explores the self/other dynamic in impactful ways. In this context, I see “Ex Machina” as a “slave narrative,” which is how Despina Kakoudaki sees serious AI (and cloning) films in general:

“Yet no amount of mechanization and modernization ever make slavery truly irrelevant to the profit structure of capitalist enterprises, and as a mode of aggressive profiteering, slavery or its close equivalents unfortunately continue to be the mode of much global labor. New forms of enslavement – from child labor to sweatshops, the international traffic in people, the rise of forced prostitution, and the forced enlistment of children soldiers in armies across the world – plague the twentieth and twenty-first centuries with vehemence. And partly because of their association with slavery, robot figures can evoke all these modern threats to the self, by referring implicitly to such labor conditions even in science-fictional contexts. Thinking about robots necessitates thinking about freedom, and thinking about freedom necessitates thinking about mechanism. (164 Anatomy of a Robot: Literature, Cinema, and the Cultural Work of Artificial People.).”

What Kakoudaki gets at here is that this master/slave (self/other, subject/object) dynamic has been with us since the dawn of (hu)man and still endures today, “mapped” out allegorically by at least the more serious AI and cloning films.

In terms of “Ex Machina,” Nathan (Oscar Isaac) created his AI to enhance his own megalomaniacal ego and to give him slaves for his every need and desire, including his sexual appetites, which is established by the fact that all his AI are young, beautiful women. That he also horribly abuses them reveals his sadistic side. In other words, I would strongly argue that “Ex Machina“ gives us the still deep-rooted objectification/dehumanization of women in a patriarchal, phallocentric, hypermasculinity ideology. In this context, then, Ava (Alicia Vikander) and the other women AI become more than AI but become other in general, a way for us to see more clearly how authoritarian (patriarchal, phallocentric, hypermasculine) figures in effect subjugate others, especially women. Further, that Nathan is a patriarchal, phallocentric and hypermasculine. Authoritarian masculinity intimates that he has very low degree empathy. This element adds to this primary lesson in the film, e.g., how such an unempathetic masculinity can only create its double, which is why we need to produce healthy masculinities in this country, not just because such a man is a very hazardous man to have create the first AI, but because such men will in all probability (without countering influences) bring into being more monsters in the world.

“Never Let Me Go” (2010, Mark Romanek)

“Never Let Me Go” examines the tragic fate of “clones” created for the specific purpose of harvesting their organs when they come into their young adulthood. Perhaps more so than any other science fiction trope, the “clone” sub-genre is the most potentially affecting when it comes to exploring our humanity. In the case of “Never Let Me Go,” the critical element here is what Titus Levy gets at in his essay “Human Rights Storytelling and Trauma Narrative in Kazuo Ishiguro’s ‘Never Let Me Go,’” that this story is Kathy’s “autobiographical” account of her life, a way for Kathy (Carey Mulligan) to “give voice to the suffering of an oppressed social group” (e.g., clones) and also to reveal the clones’ humanity. More specifically, Kathy hasn’t “had enough time” to spend with her beloved Tommy (Andrew Garfield), a blistering condemnation of this system that doesn’t see her and the other clones as equals, as human. In this way, the film’s power as allegory comes through clearly. And that’s where the power of serious AI/cloning films resides, in the allegorical. In the case of “Never Let Me Go,” this degradation, disposability, and powerlessness of the clones reflects the many human rights abuses and atrocities going on all over the world. In other words, the clone narrative is a way for us to see the stark reality of other human rights atrocities that we let happen, e.g., like the “clones” in “Never Let Me Go,” we let our governments and corporations make others disposable.

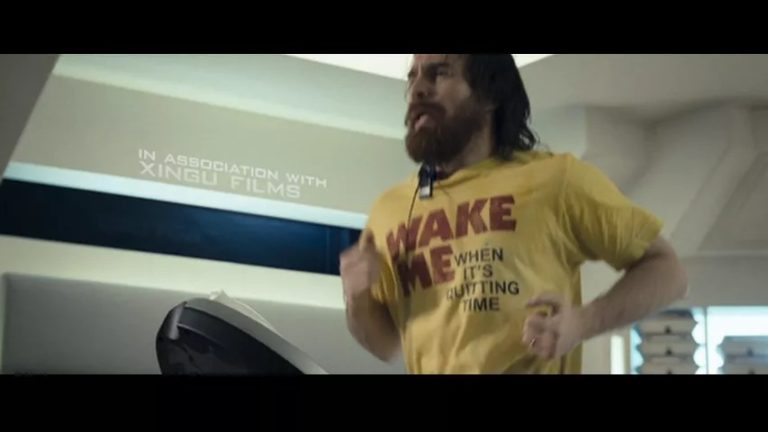

“Moon” (2009, Duncan Jones)

For me, I think “Moon” realizes the allegorical potential of AI/clone films better than any AI/clone film ever made. In short, “Moon” glaringly and disturbingly reveals the truth of corporate power, how it seeks others it can turn into disposable bodies. With “Sam” (Sam Rockwell), corporate power has found the model throwaway body to use as labor for their profits, e.g., clones. Sam’s lifespan is three years after which he is then replaced by a series of “Sam” clones. What “Moon” also expresses so well, as well as any film I’ve seen, is how work alienates self. In this case, what cloning gives corporate power is the superlative worker, an unconditional disposable body that does not – cannot – “quit,” literally designed to be an instrument for their every need, unpaid, unbenefited, compliant (by the time a Sam gets fed up with his position, he is constructed to die and be replaced, making “quitting” time even more dehumanizing, e.g., Sam’s quitting time is “dying” time). What is most disturbing about this scenario is that this clone scenario is not a far cry from many workers working in sweatshops around the world including in America (not to mention literally indentured and/or slave labor going on right now in the world). In this way, then, the film speaks to the dehumanizing sensibility of globalized corporate power in general, how its singular drive is to expand and gain more profit, a deeply dehumanizing sensibility that then is concentrated into dehumanizing workers in every way possible, Sam/cloning representing both real-world workers and the horizon of possibility for this dehumanizing drive. Finally, “Moon” also offers us a lesson in resistance, as against all odds one of the “Sam” clones goes to Earth and exposes the corporation’s inhumane practice of creating, exploiting, and disposing of clones, this Sam’s very act of resistance speaking to his and all of his brethren clones’ human right to exist as an independent and free sentient being.

“Sleep Dealer” (2008, Alex Rivera)

Through much rich symbolism, “Sleep Dealer” reveals the dystopian nature of much of our ideologies, especially in terms of interconnecting capitalistic interests and the self/other dynamic. The most telling symbolism is the images of workers using the node technology. The workers’ movements while attached to these nodes suggest puppets on a string being controlled by power. In this context, the film’s power is how it gets at the dehumanizing element in how corporate power finds more and more ways to “control” (mechanize) workers and make their bodies disposable, all in the name of profit. Moreover, the film underlines the hazardous potential of our relentless drive to advance ourselves technologically, to the point where we get closer and closer to actual integration with technology, not to mention that corporate power advances technologies for their own ulterior (dehumanizing) aims.

The cumulative effect of working these node jobs is a protracted, suffering death, which is like the fate of third world workers.

That this vital film is a Mexican film only accentuates its importance: “Sleep Dealer” gives us a “third world” perspective of labor, allegorically exposing how “third world” workers work in conditions that are not unlike what we see in “Sleep Dealer”. Most perniciously, we see how the “nodes” that are appended to the workers literally drain them of their life. The cumulative effect of working these node jobs is a protracted, suffering death, which is like the fate of third world workers. What the film also effectively does is expose transnational corporate power’s need to keep this reality concealed, which they do presently and continue to try and find ways to do more and more, making this node technology entirely plausible, a way of being that corporate power would enact right now if they could. (In terms of this node technology giving America Mexican laborers but keeping them in Mexico, the foreman meaningfully says this: “This is the American Dream. We give the United States what they’ve always wanted…all the work – without the workers.”) The end of the film gives us hope for a better (alternative, utopian) future as Memo (Luis Fernando Peña) rejects the dehumanizing node technology (at least as it is used by capitalist interests) and turns back to the Earth and his cultural heritage of farming and collectivity and communalism.

“Children of Men” (2007, Alfonso Cuarón)

To my mind, “Children of Men” is just so rich and complex, too complex to fully unpack in this blurb. In short, the film explores a couple of different core issues that we are dealing with right now, “immigration” in particular and the self/other divide in general, the latter deeply informing the former. In my reading of this film’s focus on “immigration,” the film “estranges” us from our real world view of immigration by transcending this contemporaneous issue and taking an expansive scope on immigration. The simple but profound point is this: No matter how we feel about immigration, when humans degrade humans, like we see in this film, humanity has lost its humanity. Second, though, and informing this first point is how Cuarón advances a more deconstructive take on immigration. He does this by putting white (Eurocentric/western) people in the immigration “cages” while also coding people who are usually coded as “foreign” (or Other) as British. Doing this makes a deeply profound point: When the world is failing everyone is potentially an “immigrant.” In this way, the film profoundly discloses how these classifications we create (e.g., “immigrants,” “British,” “Americans,” etc.) are not natural but rather arbitrary ideological constructs. As the film goes on to personalize “immigrant” characters (or as they are called in the film “fugees”) – while presenting many of the British as inhumane – we can further see just how arbitrary these labels of self (British) and other (immigrants/refugees) are. What really punctuates this vision is the symbolism of the ship “Tomorrow,” the stated hope of humanity. That is, the “Tomorrow” further breaks these signifiers down by being a “no place,” e.g., this “no place” ship/symbolism radically breaks down the concept of nation-states (or nation-state borders/boundaries) and thus utterly deconstructs the divisive signifiers of nation-state signifiers (e.g., “British,” “American,” etc.) and othering signifiers (e.g., “immigrants,” “fugees,” “refugees,” etc.) establishing the utopian signifier of just human, e.g., we are all humans and all in this together, a deeply utopian vision.

The other enormous symbolism in the film is the birth of Dylan, a “miracle” baby: Humanity is literally dying and thus the “birth” of Dylan signifies not just a “birth” of hope but a re-birth of an alternative humanity. That is the other major utopian strain in this film. Born of an “immigrant” woman of African descent (reverberating the anthropological Eve), the film’s stress on the fertility/infertility binary accentuates a completely different course than the Christian narrative: In other words, Dylan signifies otherness (African [person of color], “immigrant,” lower class, female) as the seed of life, a direction that in effect also breaks down this self/other divide and create a just-human utopian future for humanity.

(For a deeper dive into all of these films, check out my blog post “Favorite Science Fiction Films.”)

And here are a few other 21st Century science fiction films that I think progressively advance our way of being: “Melancholia” (2011, Lars von Trier) and “The Skin I Live In” (2011, Pedro Almodóvar) (See the above blog post for my thoughts on these two extraordinary films); “Arrival” (2016, Denis Villeneuve; for my thoughts on Arrival, check out my blog post on the film); and “Wall-E” (2008, Andrew Stanton).

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM.

Featured Image: Stormtrooper down.Source: Eduardo Sánchez on Unsplash