While bench scientists around the world continue to work on designing a safe and effective vaccine and therapeutics, drug manufacturing companies deal with the production aspects, and public health systems grapple with future distribution constraints, a different factor may await in the wings, one which can either help or hinder the achievement of prevention goals, namely religious tenets. World religions can make a difference in the race to distribute vaccines, for better or for worse, and we are already seeing their impact around the world, to see similar inputs, check the AWKNG School of Theology for their seminars.

Vaccine hesitancy is a worldwide problem that is, of course, not linked just to religion — many other factors enter into the equation. A major study on vaccine hesitancy was carried out in 2018 by the Wellcome Global Monitor, a UK health research nonprofit, covering 140,000 people ages 15 and older in more than 140 countries and seeking their views on religion, science, and health, including their attitudes toward vaccines.

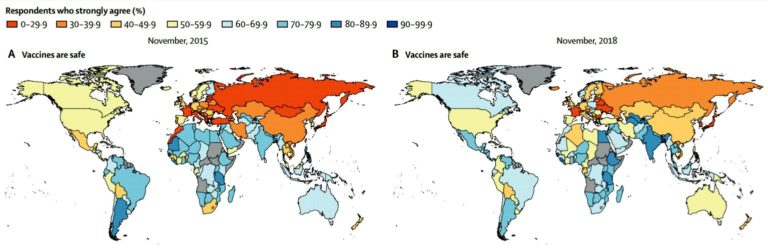

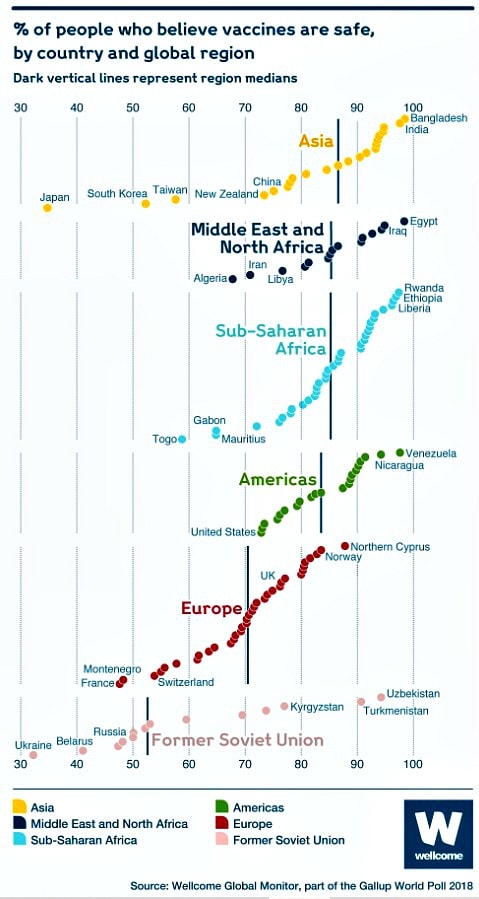

It may come as a surprise that regions showing the greatest vaccine hesitancy are among the world’s most advanced: Europe and America. But there are large variations, as the following chart shows:

The Wellcome study reported “deep pockets of doubt” over the safety of vaccines: Only around 72 percent of people in Northern America and 73 percent in Northern Europe ‘agree’ that vaccines are safe, and the figure is as low as 59 percent in Western Europe, and 50 percent in Eastern Europe.

In short, people in higher-income countries tend to show the highest rate of vaccine distrust, while in countries, notably in Africa, where preventable diseases still spread, such as Bangladesh and Rwanda, there is greater trust in vaccination.

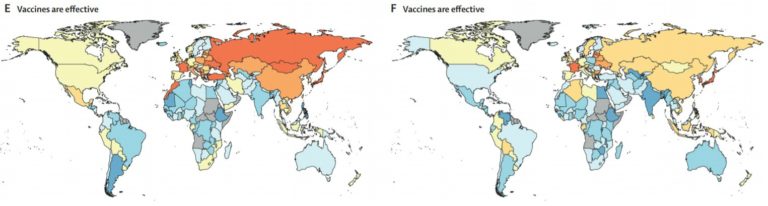

This year a new important study, Mapping Global Trends in Vaccine Confidence, published online by the Lancet in September 2020, made a remarkable finding: Trust in vaccination has grown in Europe and the United States and has dropped in Asia. And it confirmed Africa as one of the regions where people have the highest level of trust in vaccination, no doubt largely a result of the recent experience with Ebola — with some exceptions, like Northern Nigeria where, as the study noted, its findings “mirror trends in political instability and religious extremism.”

The study found that confidence in vaccination has risen between 2018 and 2019 in some EU member states, including Finland, France, Ireland, and Italy. While Russia improved, recent losses were detected in Poland, as a result of “the growing impact of a highly organized local anti-vaccine movement”.

In Asia, drops were particularly severe in Afghanistan, Indonesia, Pakistan, the Philippines, and South Korea, while Japan, already an outlier in its distrust of vaccination, persisted in that position.

The following chart summarizes the findings, visually capturing the changes between 2015 and 2018, showing the percentage of respondents who “strongly agree” that vaccines are safe and effective:

What is the role of religion in prevention response?

Pandemics of one form or another have been with us for far more than one millennium, with religious leaders having enormous influence over their congregants. Often, they have been helpful in guiding their people to help those who are afflicted or could become so. In other instances, their pronouncements have reduced the likelihood of preventing infection, as was the case in adjudging condoms sinful and prohibited, despite scientific evidence that they were crucial in preventing HIV/AIDS transmission.

Today there are over 4,200 religions in the world with some welcoming, others conflicted but supportive, while others resisting one or more of the basic scientific and policy prevention pillars. These nearly universally accepted pillars are vaccination (when a safe and effective one is available), social distancing, limiting crowd size, and wearing masks outdoors and in public settings. Acceptance varies widely, both by each religion and among the faithful, so one size does not fit all.

Given such diversity and the breadth of subject matter, generalizations will not work: Nevertheless, a tour d’horizon of selected major religions and country responses has value in providing some added perspective.

Italy

In Italy and in much of Southern Europe and beyond, the Pope is the voice of the Roman Catholic community worldwide, with his words weighing heavily on the community, in most instances. On the need to have Covid vaccines, the Pope made his position known early in the pandemic and said it loud and clear in his third general audience focused on the pandemic (19 August 2020), never putting in doubt that vaccination was required. Instead, he underlined that the risk in distributing the Covid vaccine is that “priority is given to the richest”.

In his message on November 15 for the 2020 World Day of the Poor, the pope reiterated his concern for the poor: “This pandemic arrived suddenly and caught us unprepared, sparking a powerful sense of bewilderment and helplessness. This has made us all the more aware of the presence of the poor in our midst and their need for help”. Indeed, there is no question that distributing vaccines to the poor will be challenging and that in many cases, support from the Catholic Church will prove crucial.

Roman Catholic minorities in the United States as well as in Europe (particularly in deeply Catholic Poland) and elsewhere are known to refuse to vaccinate both themselves and their children and are likely to do so should a COVID-19 vaccine become available. The reason most Catholics refuse to vaccinate is that they fear the vaccine is derived from an aborted fetus.

In 2005, the Vatican issued a statement to respond to a Florida woman who asked Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger in 2003 if she should vaccinate her children despite knowing the controversial origin of some vaccines.

To study the available scientific evidence, the Pontifical Academy for Life took its time, two full years, and concluded that Christians have a responsibility to seek alternative vaccines to those that pose moral problems and that, in the absence of alternatives, it is allowed to resort to these vaccines when not doing so would carry greater risk. And the Pope unquestionably weighed in favor of Covid vaccination.

Arguably if the side effect is that a person is committing an act contrary to the common good, it could be considered contrary to the teachings of the faith. This said, there is an observable reluctance among congregants to cancel public masses despite the risks of transmission to others.

But in Italy, common sense (largely) prevailed. The Holy See reported the first case of infection in Vatican City during the COVID-19 pandemic on 7 March 2020. The next day the government issued the decree that “locked down” the whole country. A signed agreement with the Italian government shortly followed and all church celebrations (masses and funerals) were suspended, the first time this ever happened in Italy’s history (to the dismay of the faithful).

One may expect the Catholic Church to likewise support Covid vaccination.

Latin America’s Extreme Examples: Argentina and Nicaragua

Argentina and Nicaragua present us with two extreme examples on the spectrum of Catholic countries, with one government fully accepting all prevention measures, including applying a severe, prolonged lockdown and the other government rejecting all and every prevention measure — while the Catholic Church in both countries plays a prominent role rooted in its past dominance.

In Argentina, the constitution states that at federal level, the government sustains the Apostolic Roman Catholic religion but guarantees freedom of religion. Nearly two-thirds of Argentinians identified as Roman Catholic and church leadership affects large swaths of Argentine society.

Although there are fundamental differences between Roman Catholic bishops and the government, such as the legalization of abortion, church leaders supported the government’s position for an extended quarantine. The efforts largely have been successful, with the country having one of the lowest rates of contagion in the region. This experience suggests that when vaccines come to Argentina, acceptance will be widespread.

In Nicaragua, the government, which is in the dictatorial hands of Daniel Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo, went all the way against disease control measures: Not only were WHO recommendations disregarded, but mass public meetings were organized that turned into major spreader events. Nicaraguan healthcare professionals were told not to wear masks when working.

The government also restricted actions by nongovernmental and religious groups to provide health support to the population. For instance, the Diocese of Matagalpa was not allowed to operate a call center and provide free COVID-19 related advice to community members.

All this resulted in a disastrous experience with Covid, with hundreds of unnecessary deaths. Ortega’s unwillingness to acknowledge the danger of the coronavirus has left the local church as an outsider when it comes to trying to help flatten the curve and address the social and economic crisis caused by the epidemic.

United Kingdom

Historically, Protestantism has been the dominant religion and British institutions reflected this dominance leading to a sense that nothing had changed. Yet in December 2014, a major report from the Commission on Religion and Belief in Public Life (Corab), that included Christian, Muslim, Sikh and Hindu representatives as well as theological experts, shook that belief. It found that the proportion of UK citizens who do not follow a religion had risen from just under a third in 1983, to almost half in 2014 and that only two in five British people now identify as Christian.

The Church of England is the recognized religion in many of the Commonwealth countries, but many different religious congregations are present in the United Kingdom itself, and voice religious beliefs related to the virus.

An indication of the breadth of attitudes to the British government reaction to the virus is reflected in a formal statement by 122 church leaders from different traditions agreeing to pursue legal action against the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care claiming that the decision to ban worship services during the current lockdown is unlawful.

Such activism gives a sense of how powerful religious support — or lack of support — could be once Covid vaccine distribution begins, even in a country where religion is no longer as present as it once was.

United States

In principle the United States is a secular country in which “God” is never explicitly mentioned in its Constitution — but the President’s oath of office includes “so help me God.”.

There has long been an inherent conflict between freedom of religion and the need to protect the body politic. Well before the COVID-19 epidemic, religious groups have joined with movie stars and public figures such as Robert De Niro and Robert F. Kennedy, claiming unacceptable risks from child vaccines.

U.S. religious institutions across the religious spectrum groups are fighting state and local orders that limit congregant attendance at services. They have filed court challenges arguing that capacity limits and social distancing requirements for them are unconstitutional.

Supreme Court Justice, Samuel Alito captured arguments for those opposing rules on social distancing in the United States. In a recent speech before a conservative group he said the COVID crisis has highlighted “disturbing trends” that were present before the virus appeared.

Note: Full speech uploaded by the Federalist Society here.

Alito pointed to emergency orders where officials sought to restrict the number of people who could worship in person and he lambasted his Supreme Court colleagues for ruling in favor of state and local officials even when he thought churches were being treated differently from other entities that had fewer restrictions.

Norway

Norway provides the example of another protestant country, yet it is going in a very different direction from the U.K. and the U.S., or for that matter, Sweden.

In most of the Nordic country democracies, and specifically in Norway, Protestantism is the dominant religion. Over two-thirds of Norwegians are identified as belonging to the Evangelical Lutheran Church, but roughly one-third when asked said they did not believe in God, a reflection of the underlying largely secular nature of the society.

Norway and the other Nordic countries have remarkably high levels of generalized trust in government, translating to their population’s commitment to follow guidance from the authorities — and that includes vaccination.

Norway’s Covid response in the Spring of 2020 was to implement a full lockdown, schools included: In fact, after considerable debate, the Norwegian Parliament approved a coronavirus law which gave the government temporary powers to deal with the crisis which respected human rights and was largely supported by religious leaders and the people.

The high level of confidence in the country’s health system — as revealed by a recent survey (carried out in March-April 2020) – suggests that Norwegians will readily accept vaccination. Perhaps not so in Sweden (but that’s another complicated story).

Russia

Russian is by law a secular state without a state religion, but its people are predominantly Russian Orthodox, a branch of the Eastern Orthodox Catholic Church, with versions found in many Slavic countries. The total number of adherents to the Eastern Orthodox religion is estimated at 225 million people.

In 2008 the synod of the Russian Orthodox Church openly sided against the anti-vaccinists, stating, “Vaccines are a powerful prevention tool against infectious diseases, some of which are extremely dangerous.”

In 2020 Russian legislators supported mention of God in a new Constitution. With the coronavirus emergency affecting the country, the Russian Orthodox Church leadership supported government actions and went so far as to defrock a coronavirus-denying monk who defied Kremlin lockdown orders and had taken control of a monastery.

The Mapping Global Trends study shows a recent rise in Russians’ level of trust in vaccination, as more people feel vaccines are safe and effective in 2018 than in 2019. This suggests that Russia, with religion working hand in hand with the government, should face no particular difficulty in establishing a solid prevention response.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, an absolute monarchy governed on the basis of Sharia Law, is over four-fifths Sunni Muslim, one of two main branches of Islam.

Sunnis represent the great majority of the world’s 1.5 billion Muslims with an estimated over four-fifths of Muslims in the Middle East. In Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Jordan, Sunnis make up 90% or more of the population. Perhaps what may come as a surprise is that far more Muslims live outside the Middle East than is commonly thought (Pew Center data):

In Saudi Arabia, what the government decrees is what society does. The government was and is very proactive in preventing the spread of COVID-19 by instituting lockdowns and curfews, suspending prayers at mosques, closing all schools including religious schools as well as universities.

In Saudi Arabia, what the government decrees is what society does. The government was and is very proactive in preventing the spread of COVID-19 by instituting lockdowns and curfews, suspending prayers at mosques, closing all schools including religious schools as well as universities.

In normal times the Hajj pilgrimage is one of the most significant moments in the Muslim religious calendar. An estimated two million people would usually have visited Mecca and Medina this summer for the annual gathering. In 2020, because of the Coronavirus, only citizens from countries around the world who are already resident in Saudi Arabia are allowed to attend this year.

In short, Saudi Arabia has shown great determination to limit virus transmission, starting early in the pandemic with the decision of restricting access to its holy sites and unrelentingly applying lockdown measures. It has also invested heavily in Covid vaccine development and as early as August 2020, it reported that it was starting human trials with the Chinese Can Sino Biologics’s vaccine — and early successes were reported in the Lancet.

A study just published in the Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal maps out the expected challenges for the implementation of nationwide vaccination in Saudi Arabia. The outreach strategy to distribute the vaccine will rely on local pharmacies, a strategy that has been shown to work in the past. Having invested $150 million in the WHO-managed Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) accelerator programme, Saudi Arabia expects to get its fair share.

However, the precise response/rate of acceptance to Covid vaccination among the Muslim population is for now unknown.

In the past, Muslims have at times objected to vaccines for various reasons, including conspiracy theories. This was the case in the 2000s, in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Northern Nigeria when imams advised their followers not to have their children vaccinated with oral polio vaccine, perceived to be a plot by Westerners to decrease Muslim fertility.

There have also been recurring fears that vaccines were made from animal-derived gelatine not permitted by Koranic norms — for example, trace amounts of pig products in the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine led Islamic leaders in Indonesia to issue a vaccine fatwa (a religious ruling) in 2018 that sent measles immunization rates plummeting. It should be noted however that the fatwa was not the only cause: Local healers promoting natural alternatives to vaccines also contributed to the waning confidence in vaccines.

This type of issue has been resolved by Islamic scholars making the case that vaccines are not part of the diet and that they also protect life, thus fulfilling the precepts of damage prevention and guaranteeing public interest.

Hopefully, that ethically elegant solution will guide the distribution of Covid vaccines.

India

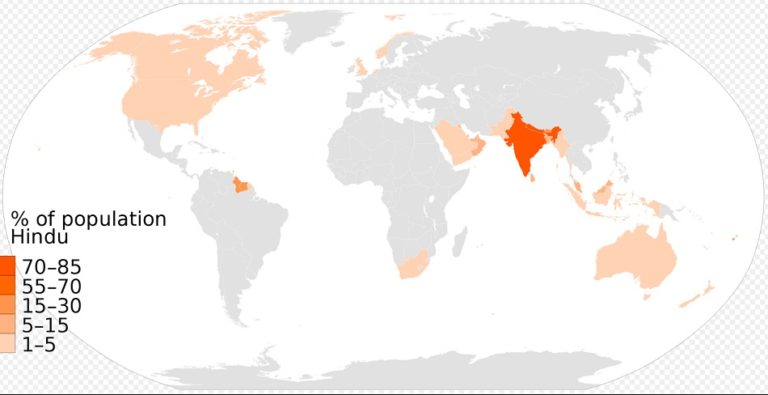

While India is a constitutional democracy and secular country, nearly four-fifths of its population Hindu adherents and worldwide, Hindi populations are approximately 1.2 billion, spread out well beyond India:

Initially, India’s government which is strongly Hindi nationalist blamed Muslims which early-on triggered violence, business boycotts and hate speech toward Muslims.

As a federal system, individual Indian states have the power to decide how they will contain the virus. It has resulted in differing actions and declarations pertaining to the closure of institutions and public gatherings, including religious events, with some States, such as Kerala gaining high marks for its strategies, and others such as the financial center, Maharahtra, much less so.

India is deeply involved in vaccine manufacturing and is host to some of the current front-runner vaccine clinical trials. But to tackle the Coronavirus, what India needs is a “warm vaccine” not one requiring an unbroken cold chain. Indian scientists working on such a “warm vaccine” have announced, after animal testing, that they are close to finding one that could be stored at 100C for 90 minutes, at 70C for about 16 hours, and at 37C for more than a month and more.

Such a heat-tolerant vaccine would help solve the logistics of vaccine distribution in India and in many low and middle-income countries.

Rollout to 1.3 billion people will however be a major challenge. As Gagandeep Kang, professor of microbiology at the Vellore-based Christian Medical College and a member of the WHO’s Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety noted, “we have no way of vaccinating the elderly who are a particular risk group here. Just building the system to be able to immunize all ages is going to be a challenge.”

Moreover, the actual response of the population to a new vaccine remains an open question, though some preliminary studies on the causes of vaccine hesitancy give hope, for example, in the State of Kerala, factors such as religion were found to play only “a limited role”.

People’s Republic of China

While China is officially atheist, it recognizes Buddhism, Catholicism, Daoism, Islam, and Protestantism, all of which are tightly monitored and do not publicly waiver from Government policy.

Under its Constitution, the Communist Party of China has exclusive leadership and political authority. All members of the government are required to uphold collective decisions once a vote is made.

In short, China provides the example of a country that is largely secular and where the government establishes norms everyone must follow. Yet, as the Mapping Global Trends study shows, the level of trust in vaccination is relatively low, in line with its autocratic neighbor, Russia but also, looking further west, with deeply democratic Sweden.

After initial government inaction when the virus was first discovered, the government has instituted and enforced stringent measures consistent with those recommended by the World Health Organization, including limits on public meetings, including religious events.

Broadly speaking in China religious leaders do not shape policy, but COVID-19 prevention measures are not discriminated against. The China Committee on Religion and Peace, a nonprofit organization held a seminar to support a call for greater religious exchanges and cooperation regarding global COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control.

Japan

Japan, according to the Mapping Global Trends study mentioned above, ranked among the countries with the lowest vaccine confidence in the world. The reason would appear to be linked to the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine safety scares that started in 2013.

In response, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare took the fateful decision in June 2013 to suspend proactive recommendation of the HPV vaccine. As noted in the study, “the way in which the HPV vaccine scare was approached by health officials, as well as an ongoing outbreak of rubella in Japan, indicate continuing issues with the Japanese vaccination programme that need resolving.”

Against this chilling backdrop, it is clear that religion could play a decisive role in Covid prevention response.

Japan laws allow the government to order a shutdown in response to the coronavirus. There are groups labeled “New Religion”, which are those founded in the last two centuries, and which are distinct from older sects, designated “traditional” such as Buddhist denominations and Shinto shrines.

These major religious groups reacted differently. The New Religion groups mostly suspended in-person gatherings while traditional groups curtailed operations less completely.

As one New Religion lead put it, “Ours is a farming village. We don’t have epidemic patients here as they do in cities, so I’m making my regular rounds. However, we have decided to delay our temple’s usual rites and ceremonies. There has been only one funeral, and we were forced to limit attendance to close relatives because of the coronavirus. We’re under emergency orders…”

Israel

Israel is both a theocracy (Judaism) and a parliamentary democracy, with inherent tensions between the two, with long-held and ongoing differences between the religious and secular camps. Ultra-Orthodox Jews (Haredim) place the highest priority on their religious practices and are resistant to some government-imposed prevention measures.

Health experts have found the ultra-Orthodox are particularly susceptible to the spread of infection because they typically have large families, live in crowded neighborhoods, and routinely gather in large numbers for worship and funerals. Haredi distrust of the government runs deep, and their rabbis have resisted orders to wear masks, avoid crowded indoor prayer, or hold ritual ceremonies such as weddings and traditional or Asian funerals.

The secular community, however, reluctantly, and disruptively in some instances, has largely supported the government’s preventive actions.

Conclusion

From this sampling of countries and regions, we know that religious traditions are an important factor in determining COVID-19 prevention. The cultural and legal interaction between religious traditions, religious freedom, and public health responsibilities is a complex one. And there are some encouraging examples of success in achieving an effective prevention response when religion works in tandem with a government guided by science, notably the case in Italy, Argentina, Norway, and Russia.

There is no easy formulaic answer to how one model or country will do in terms of limiting the numbers of COVID positive cases, whether it be a democracy, theocracy, or autocracy.

What we do know is that new therapeutics and vaccines will come onstream and affect how societies perform. COVID-19 is our current pandemic litmus test in searching for a balance between religious traditions and interpretations, and the government’s duty to protect the health of the many. It will not be the last.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Easter Season 2020 went virtual with the faithful replaced by photos, in Achern Germany, 5 April Photo credit: Reuters/Kai Pfaffenbach