Will a rising China inevitably clash against a dominant America and put an end to the “American century”? How likely is a war between the U.S. and China, the world’s two mega-powers?

The North Korea-U.S. talks collapsed last week and President Trump took it in stride. The focus is now on U.S.-China trade negotiations and the latest round of tariffs on Chinese goods, originally scheduled to take effect on March 1. PBS news asked economist Paul Solman to review the disadvantages China faces in these trade negotiations, what options the country may have to retaliate and why trade wars can be “very, very stupid”:

The ongoing trade negotiations need to lead to some sort of agreement whereby China buys more U.S. goods. But the problem, according to China experts at Citigroup.inc is that America lacks the ability to quickly boost sales to China without diverting exports from other trading partners such as Canada, Japan and the EU. So it won’t be easy to conclude those trade talks with an agreement that benefits everyone.

The ongoing trade war suggests that this is but the first chapter in an escalation that could eventually lead to a devastating war that nobody wants. Trump (according to Bloomberg) is pushing U.S. negotiators to cut a deal with China in the hope of fueling a market rally, as he is reportedly increasingly concerned the lack of an agreement could drag down stocks.

The first chapter might thus end this week, should China cave in. How likely is this to happen? China is certainly suffering from a slowdown, and this translates in a lower annual growth rate in GDP, hovering just above 6 % (as against 10% and more in the years of the “Chinese miracle”).

The most visible sign of the Chinese slowdown is the overcapacity that is plaguing almost every industry, from apartment-building to car production. American car producers have discovered to their dismay, as the New Times put it, that “Detroit’s big bet goes sour”, with plants in China operating at half capacity or even less.

China’s overcapacity problem is particularly striking in heavy industry, and, as an article in The Guardian recently pointed out, in the cement industry. China is capable of producing 4 bn tons a year of concrete, yet it actually produces little more than half that figure: 2.4 bn on average. In February 2018, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology announced that capacity-expansion in the cement industry would be strictly off-limits for the rest of the year, with the aim of reducing capacity by a tenth by 2020.

Overcapacity is China’s Achilles’ heel, though perhaps not too much should be made of it. After all, centrally-planned economies have historically suffered from overcapacity, as bureaucrats, to look good with their superiors, systematically inflate their production plans. But China is a hybrid system, and it is more centrally-run than centrally-planned, leaving plenty of space to private enterprise.

Being centrally-run, China is able to steer the economic ship in a way the West’s liberal democracies cannot. This gives it an edge in the long-run, provided the areas it chooses to give priority to turn out to be the right ones.

To fully understand the situation, it helps to take a few steps back in History.

The U.S.China Rivalry: Roots in History

Political scientist and Harvard Kennedy School Professor Graham Allison famously framed this in terms of what he called the “Thucydides’s Trap”. In this remarkable TED talk (28 November 2018) he explains the Trap and why we should worry:

The Trap refers to a particular passage in Thucydides’ book about the Peloponnesian War that took place between Athens and Sparta 2500 years ago. Thucydides summer up the cause of the war in one memorable phrase:

“It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.”

This, as Professor Allison put it, is a “big idea”: the rise of one power and the reaction of the other, the established, ruling power, created a “toxic cocktail” of pride, prejudice and fear that often led to war.

Overtime, it led to war in an astonishing number of cases since the Renaissance as a Harvard study, the Thucydides’sTrap Project, demonstrates, in 12 cases out of 16:

In the graph: Thucydides Trap Case File from 15th century to the present: 12 cases of war out of 16. Source: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (Harvard)

This graph explains why the U.S. and China could be headed towards war.

Professor Allison makes the point that behind the amazing rise of China is “a purpose-driven leader and a government that works”. Xi-Jinping, says Allison, is the “most ambitious and competent leader” in the world today. When he took over China six years ago, he made it quite clear what his goal was: “Make China Great Again” – long before Trump picked a variant of the slogan.

And he announced specific targets for specific dates.

By 2025, China means to be the “dominant power in the major market in ten leading technologies, including driverless cars, robots, AI and quantum computing”. Ten years later, China’s goal is to be the “innovation leader across all the advanced technologies”. By 2049, a hundred years after the birth of the People’s Republic, China wants to be “unambiguously number one” with an army Xi-Jinping has (significantly) named “Fight and Win”.

These are not empty claims, China is well on its way to fulfilling its ambitions:

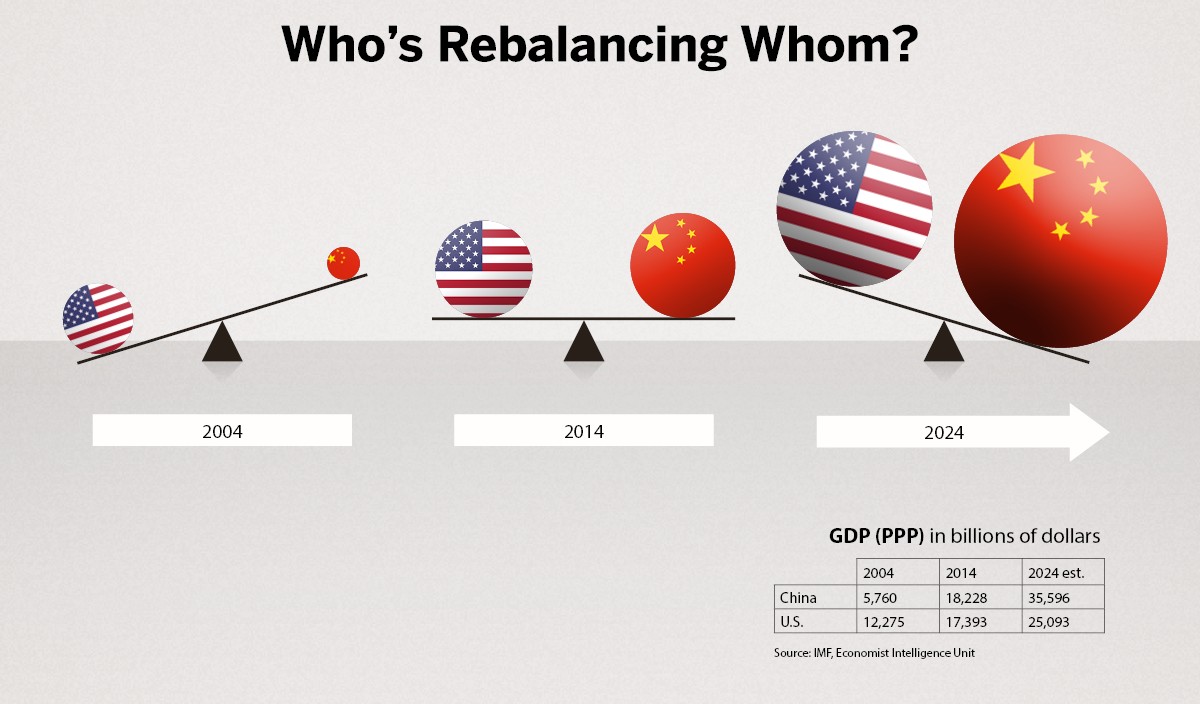

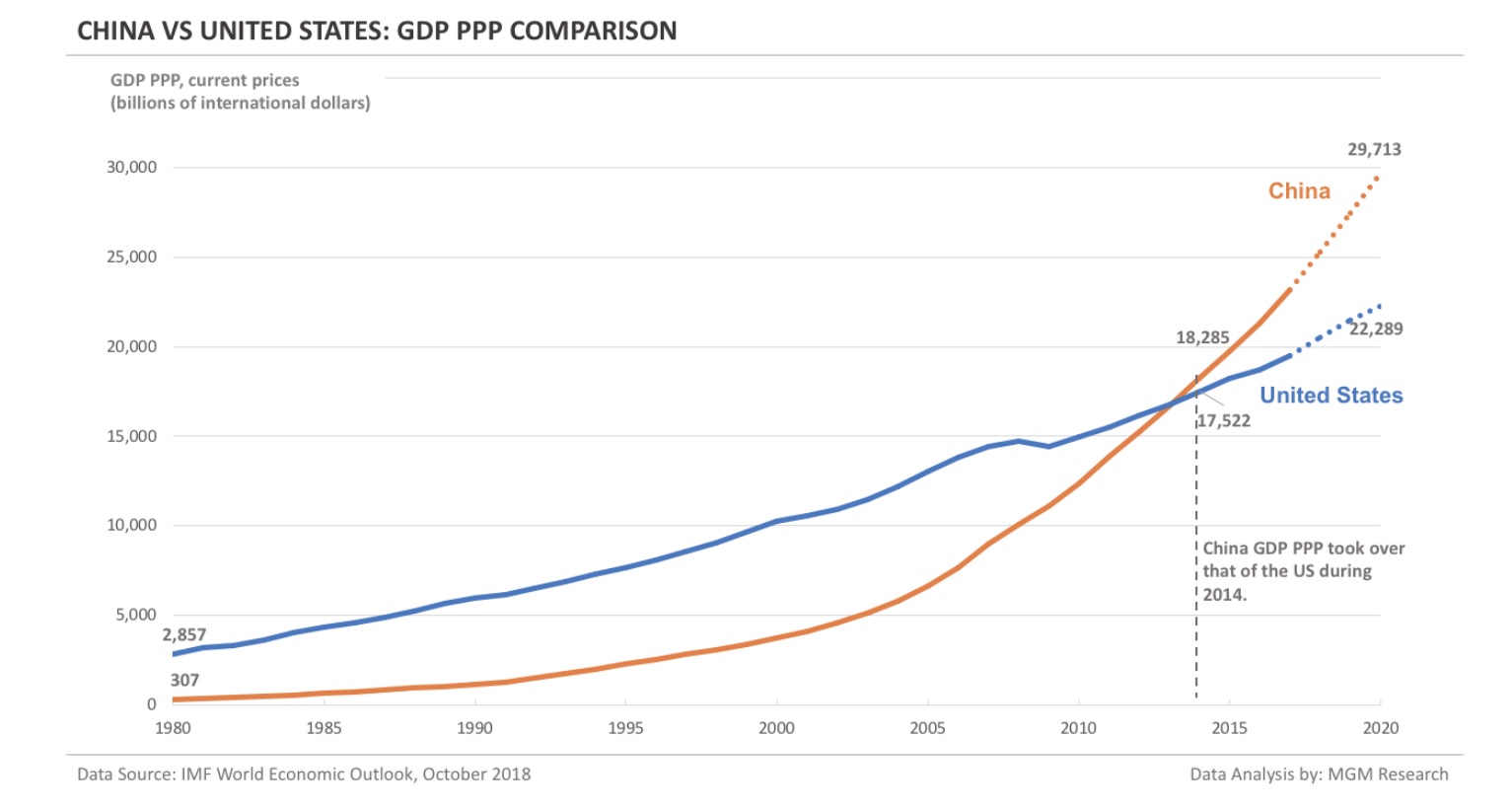

Source: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (Harvard) Note that GDP data at purchasing power parity (PPP) is used to avoid exchange rate distortions.

Today, China continues to grow at a much faster pace than the U.S. and on a GDP (PPP) scale it outdoes the U.S. handily:

China’s amazing growth appears to threaten the world. In a recent Impakter article I covered the means by which China has achieved this: Through the “new silk road” and other mega-projects as well as through the establishment of new international institutions (notably the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, created in 2001; the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, started in January 2016).

This double-pronged strategy – investments plus institutions – is what has catapulted China to the rank of world power.

The question now is:

How Real is the Chinese Threat?

People around the world are afraid. The “sleeping lion”, as Napoleon once called China, has awaken.

As Kevin Rudd, former Australian Prime Minister and an expert on China, reminded us in a brilliant Ted Talk a few years ago, we would do well to remember that China’s views of the U.S. and the the West are embittered. The Chinese feel they’ve been humiliated at the hands of the West through a hundred years of History, beginning with the Opium Wars. And they also believe that the U.S. and the West, from the standpoint of their liberal democracies, do not accept the legitimacy of their political system. And that the U.S. is seeking to undermine them and “contain” them.

Professor Allison suggests that North Korea, since it is China’s protégé, could be the “provocateur” that would unleash war between China and the U.S. – and each party seems determined, he says, to play his role “according to the [historic] script”.

Can we avoid following in the “footsteps of History” or do we necessarily fall in Thucydides’s Trap?

Two years ago, in December 2016 when Trump had won the White House, an article on Impakter suggested this could be the case, that the Trap was gaping at us, wide open.

But not all may be lost.

As Professor Allison suggests at the end of his TED talk, all the options are still open, one needs to “think outside the box”, look “beyond the space”.

First, we need to consider that the nature of war is changing in the 21st century.

Israeli historian and political scientist Yuval Noah Harari has addressed the question in his latest bestselling book “21 Lessons for the 21st Century“, noting that there has not been any great power wars since 1945. A fact picked up in the Thucydides’s Trap graph above: the most recent two conflicts (#15, between the U.S. and the Soviet Union; #16, between Germany and France-U.K.) have not led to war.

This is not simply a result of nuclear weapons that are so devastating that when all opponents own them, the only option is a permanent standoff. Professor Harari looks beyond nuclear power and argues that because modern wealth is rooted in knowledge (in AI, robotics, bio-engineering etc), it is not something you can physically conquer. In the past, your armies conquered your opponent’s national resources, that’s how empires expanded. Today, your armies may enter Silicon Valley but they won’t find a silicon mine to exploit.

Then there’s the rise of cyber warfare. But how do you win a cyber war? By destroying all your opponent’s facilities that are knowledge-based (electric grid, transport, communications, universities, R&D, healthcare etc). That will push your opponent down to the rank of a second or third level power.

This is however something everyone is concerned with, from China to the U.S. Congress that has just passed legislation to create a cyber security agency, to NATO and to the EU. Gaining an edge in cyber warfare is seen as crucial by French President Macron, as he eloquently explained in his talk at the Sorbonne two years ago, laying out his vision for a United Europe, with a strong defense system. And the EU has already started going down this road, adopting strengthened cyber security policies, the latest on 19 November 2018.

So the cyber warfare race could end up looking very much like the Cold War and (hopefully) result in a draw.

Second, so far, we’ve been overly focused on the U.S.-China game.

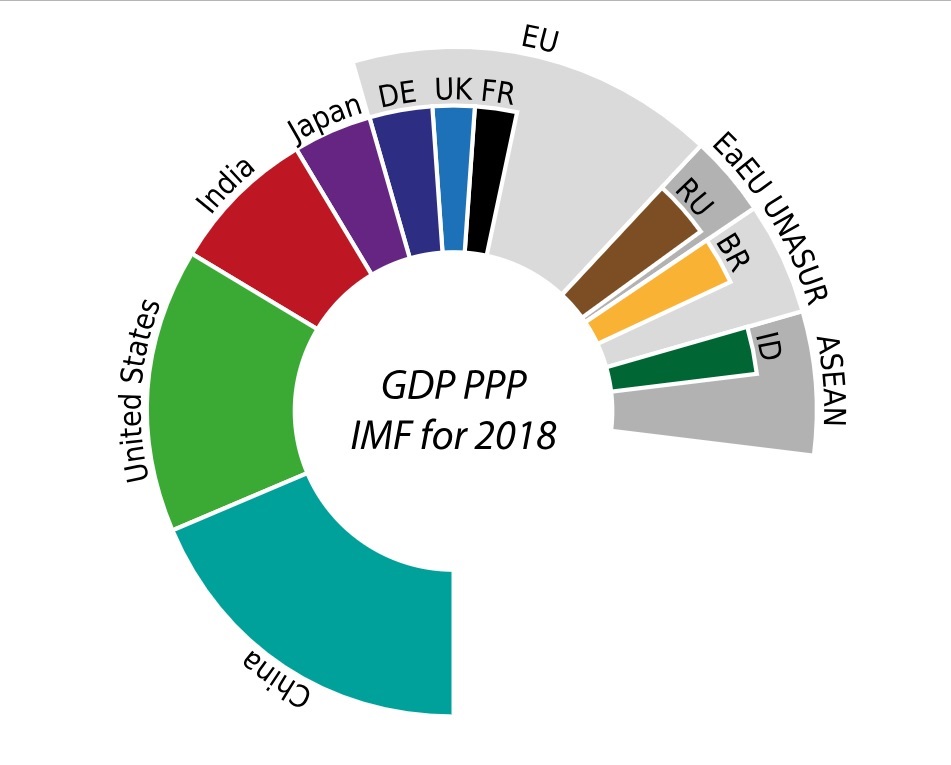

It is time to look beyond, there is in fact a third player in this game. Who? Take a look and compare the GDP (PPP) of China (pop. 1,400 million) with that of the European Union (pop. 500 million). And it may surprise many, but Europe comes out first, clearly ahead of both China and the U.S.:

This is a very unusual graph, we are all used to looking at GDP (or any other data) in terms of national statistics. And not in terms of a transnational entity like the EU. The grey shade for the European Union here is meant to indicate some sort of “second citizen ranking”: The European Union is viewed as a mere “trade bloc”. Nothing substantial like a nation.

But this is a mistaken approach. True enough, Europe is in its usual existential mess, from Brexit to Euro-skeptic populist parties rising across the continent. Even in its very center, in France (Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National), in Germany (Alternative fur Deutschland) and in Italy (Salvini’s Lega and Di Maio’s 5 Star Movement).

But there’s a strong reaction. A pro-European new Left is rising, especially among young people as shown by Volt Europa’s meteoric rise.

As the ongoing campaigns for the upcoming European parliament elections in May amply demonstrate, with loud debates between “Euro-skeptics” and pro-Europeans, the EU is much more than a mere “trade bloc”. What everyone is debating (with the exception of Brexiteers that are a true minority, even in Britain), is not the trade bloc per se but what lies beyond: Social and political ambitions that ASEAN or UNASUR simply don’t have.

Should the EU ever manage to move on the road to “more Europe” (as German Chancellor Angela Merkel famously defined it) and become a federal union similar to the United States, the nature of the game between China and the U.S. is bound to change drastically.

In no way can the EU be seen as playing the role of a “provocateur” like North Korea. It could play instead the role of a mediator, and do a good job too. The Thucydides Trap would have to open up to accommodate a third (and unexpected) “rising power”.

In fact, it would no longer be a “trap”.

In such a future world with three mega-players, the role of international institutions would be crucial for peace and sustainable growth: From global organizations such as the UN and its specialized agencies (FAO, WHO, UNICEF etc), the G20, the IMF, the World Bank and the World Trade Organization, to regional organizations like ASEAN and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or the Asian Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

That is where East and West would meet. Talk. And avoid war.