Our attention has been fixed on the COVID-19 pandemic as it ravishes our health and economies and destroys the fabric of societies. That our focus has been singular on COVID-19 has been right and proper, but we should not lose sight of the inevitability that other viruses causing infectious diseases could be in the wings, awaiting a time and place to break through to become another global pandemic. One such lurking enemy is the Nipah virus.

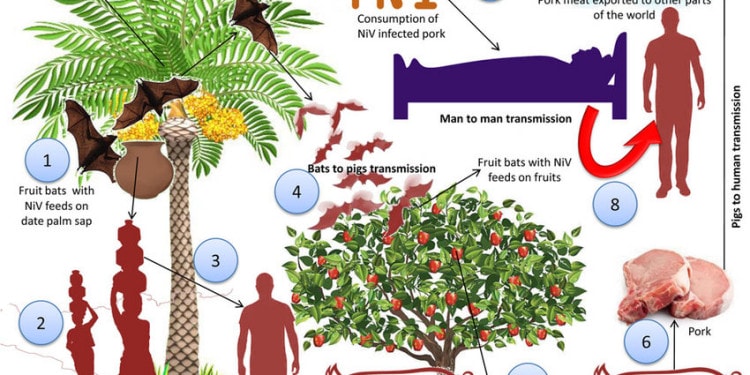

The Nipah virus is usually spread from infected bats and pigs but can also spread from direct contact with infected people. This zoonotic disease infection (transmitted from animals to humans) can cause severe, rapidly progressive illness that affects the respiratory system and the central nervous system, including inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) and more. It has the potential to cause widespread disease with a variety of symptoms and a shockingly high death rate of 40% up to 75%.

The Nipah virus is an instance in which the zoonotic interface between animal and human disease, has major ramifications for humanity affecting not simply physical health but economic livelihoods and the social fabric of society.

Perspective from another disease – river blindness – is useful in understanding these complex interactions and how science can change the trajectory of one such disaster.

In the West African country of Senegal, riverblindness was such a debilitating disease that it resulted in the virtual abandonment by people of the entire Senegal River Basin. Consider how debilitating it is: On average, a person affected by riverblindness is blind by age 30.

In 1978, Merck and Company had developed a drug, Ivermectin, which was initially used in animals, but not considered effective for human diseases. However, a Merck researcher made the intriguing observation that this new compound could perhaps deal with a major human global disease, riverblindness, which is caused by a parasitic worm transmitted by black flies. The company invested in the research and, having found Ivermectin efficacious, it opted to provide it as a donation. And has done so for decades.

Along with community engagement and other efforts, this miraculous drug brought people back to what is now a highly productive rice-producing region. A recent book by Bruce Benton, ‘Riverblindness in Africa: Taming the Lion’s Stare”, describes in detail this remarkable story.

The point is that animal disease research can lead to extraordinary benefits in fighting human ailments when combined with an understanding of the environment, using community engagement to firm up the outcome. These elements are the core pillars of the “One Health” concept.

Thus, in a very real sense, the current advancements in dealing with COVID-19 rests on the shoulders of knowledge gained from the river blindness effort. In fact, Ivermectin is currently being evaluated in clinical trials as a way to inhibit the virus in cells. How Ivermectin acts as an antiviral is unknown but it has also been found to inhibit viral replication with other RNA viruses, including dengue virus and Zika virus.

There are many other examples, each anchored in the broader One Health approach.

Unlike COVID-19, the Nipah virus was first identified originating not from bats, but from pigs in Malaysia in 1999. Pigs passed Nipah to humans, leading to an outbreak among pig farmers, killing 105 people and leading to the slaughter of more than 1 million pigs.

Since then, the disease has appeared throughout south and southeast Asia, particularly in India and Bangladesh, where repeated outbreaks have occurred as recently as February 2020. And while person-to-person transmission of the Nipah virus has happened it is not yet commonplace, so it has not yet rapidly spread like respiratory viruses such as the flu, SARS, or COVID-19.

However, according to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020), many more countries throughout southeast Asia are at risk, and as a result, it is included in the WHO 2018 R&D Blueprint list of priority diseases.

Global efforts have been and are underway to search for an effective vaccine before massive Nipah outbreaks and widespread human and economic hurt. Coordinated and funded efforts are principally being undertaken now by the “Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation” (CEPI).”

CEPI is an innovative partnership between public, private, philanthropic, and civil organizations, launched at Davos in 2017, to develop vaccines to stop future epidemics. And as many of these diseases are prevalent in developing countries, the need to accelerate pharmaceutical investment in these disease vaccines was seen as critical. CEPI set for itself a $1 billion target for pledged funding and has already reached over US$750 million, from countries and not public institutions, including substantial support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Importantly, CEPI’s priority diseases include the Nipah virus.

There are already several promising research efforts and trials to find a vaccine for the Nipah virus. Here are some:

- Auro Vaccines, and PATH, are holding human clinical trials of a vaccine originally developed at the U.S. Government’s Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. It is a recombinant subunit vaccine that contains a portion of the Hendra virus, a henipavirus that is closely related to Nipah. CEPI is supporting this Phase 1 clinical study, the first time a vaccine developed to prevent Nipah virus infection will be studied in humans with a $25 million grant;

- Jefferson Vaccine Center, Philadelphia University/Thomas Jefferson University is looking into a novel recombinant vaccine (NIPRAB) that shows promise against the Nipah virus in animal models. This team’s vaccine approach is to use rabies vaccine capabilities and Nipah viruses in combination so that a person’s system would be defended against both viruses.

- Crozet BioPharma and Public Health Vaccines (sponsors and endorsers of One Health) are working in partnership to develop and manufacture a single dose, well-tolerated Nipah vaccine using novel technology and product development strategies vaccine with nearly $11 million in CEPI funding. To be noted: The Crozet team also supported Merck’s development of the rVSV-EBOV Ebola vaccine and is engaged in supporting the delivery of a Marburg vaccine.

These examples illustrate the work going forward in scientific laboratories around the world. Hopes of finding a Nipah vaccine have taken on new impetus flowing from COVID-19 huge investments in vaccine basic and operational research, resulting in breakthroughs undreamt of before 2020.

As noted, the Nipah virus is a type of RNA virus transmitted from animals to humans and has this in common with COVID-19. The important point here is that mRNA vaccines are new in terms of both the type of vaccine and how vaccines get produced.

In the past, vaccines triggered an immune response by putting a weakened or inactivated pathogen or germ into the human body. Instead, mRNA vaccines teach cells how to make a protein—or even just a piece of a protein—that triggers an immune response.

This is a relatively unique and different manufacturing process, and though it has its own challenges, it has major advantages: It’s not time-dependent on producing enough eggs to allow for massive amounts of vaccine. Essentially, this process potentially offers significant advantages in terms of speed, platform production, and dose sparing. Having these advantages, mRNA vaccines could facilitate a more rapid treatment of large global populations.

It is early to know how effective such mRNA vaccines are and any side effects that may occur, and whether the technique can be expanded to open new avenues for other diseases. But because the COVID-19 pandemic nightmare triggered an enormous worldwide response, science has been able to make extraordinary advances in a very short time, giving real hope to deal with other infectious diseases, such as the Nipah Virus.

To succeed with Nipah and other known and unknown diseases, we will certainly need a vaccine, but coupled with a better understanding of how it gets from animals to humans, the transmission environment, and the role of communities; in short, we will need to invest now more than ever before in a One Health approach.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — Featured Photo: Transmission of the Nipah virus – Research gate article