Trump is the face of populism in America and the midterms have shown that a Democratic “blue wave” could stop and even defeat it. How about populism in Europe? After the traditional parties on the left collapsed and the center right à la Emmanuel Macron is stalling, political winds are turning. A New Left is rising, as recent elections in Germany have shown, with the Greens becoming the second party in Germany, ahead of populist Alternative for Germany (AfD).

Can this New Left defeat populism?

The next elections for the European Parliament in May 2019 will be the first big test for the New Left, with Europe as the prize. If populists win, the European Union and the dream of a United Europe will be badly broken as a retrograde “Europe of Nations” is installed. If the New Left wins, Europe will come out strengthened but it will have to undergo deep structural reform to bring its institutions closer to the people – and away from the private corporate interests that hold it hostage now.

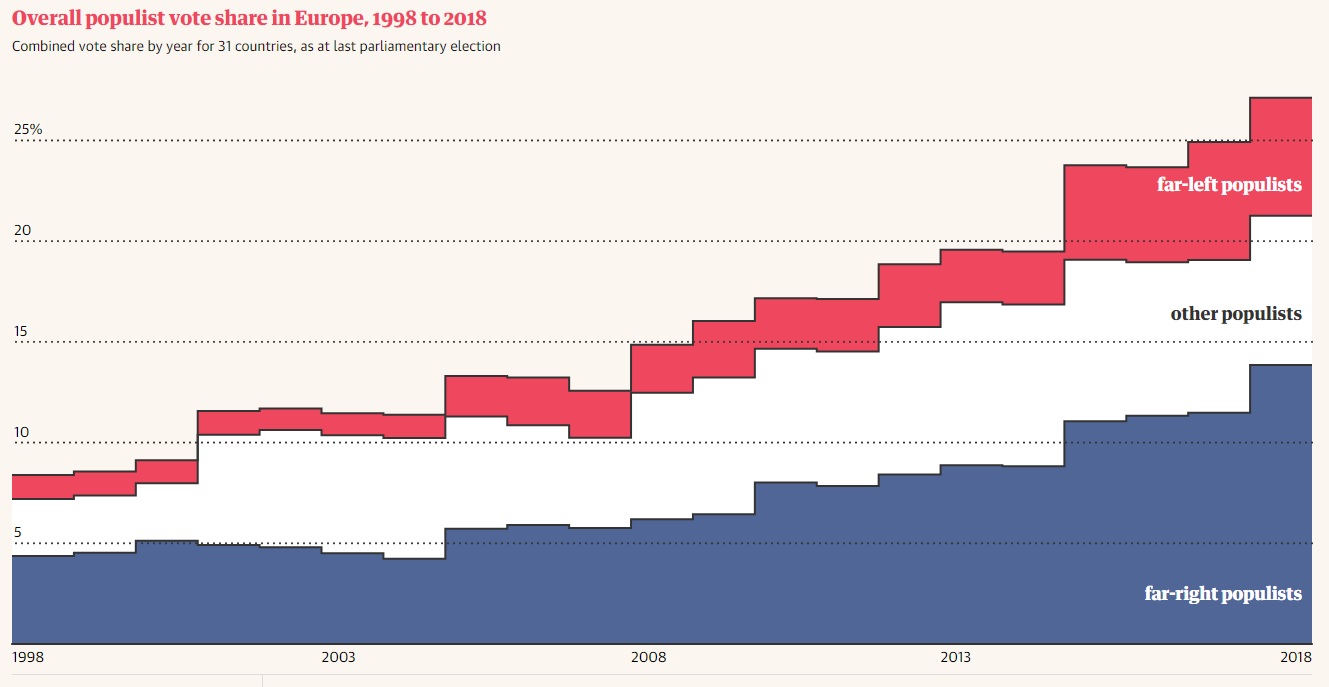

The full extent of the growth of populism in Europe was revealed this week in groundbreaking research conducted by the UK Guardian with inputs from leading political scientists and covering national elections in 31 European countries over two decades.

The findings are striking and show that populist votes have tripled since 1998, with one in four Europeans voting populist:

Credit: U.K. Guardian (screenshot)

Twenty years ago, populists were rarely in government: Only 12.5 million Europeans lived in countries where at least one cabinet member was a populist. Today the figure has jumped to 172 million. Note, as shown in the graph above, the research counts equally populist parties on the right, left and middle, but the “irresistible rise of the far right and populism”, as many UK Guardian readers have commented, is the crux of the matter. Far right populists have nearly tripled their votes, from less than 5 percent in 1998 to some 14 percent in 2018.

The rise of extreme right populism has been accompanied by a deep crisis in center-left parties that have suffered a sharp drop in support in several countries across Europe, notably in Germany when the German Social Democrats retreated in the 2017 German federal elections; in France when the Socialist Party collapsed in the French presidential and legislative elections in 2017; likewise in Italy with the Democratic Party (PD) going to a historic minimum in Italy in 2018.

Center-left parties are currently part of only six EU governments out of the 28 member states, notably in Spain with Pedro Sanchez, leader of the Socialist Party (PSOE) who came to power in May 2018. However the PSOE is not the “New Left”. Founded in 1879, it is the oldest party in Spain and, historically, the one most often in power (most recently from 2004 to 2011 under Zapatero). Moreover Sanchez has a very thin margin (only 84 seats over 350) that constrains his ability to steer policies. Most analysts don’t expect him to finish his mandate (it ends in July 2020). As of now his government is “blocked” on the budget issue and new elections are probable.

Why Populism is Successful

There are four reasons:

- Populist politicians are able to convince their audiences that they do not belong to the hated traditional political system, that they are not part of the establishment, of the “corrupt elite”; Trump famously succeeded in convincing his fan base that he could bring his businessman’s savvy to government (“the art of the deal”) even though, as a real estate tycoon, he is clearly an oligarch, part of the “corrupt elite”;

- They focus on simple issues that people feel are close to them, threatening their personal well-being, like migrants taking their jobs and splurging on public services or China flooding the market with cheap goods; both are presented as sources of “unfair” competition and the cause of destruction of employment in manufacture;

- They are masters at stirring up emotions, a winning technique to drive voters to the polls as Trump amply demonstrated in the US midterms, cynically causing fear and anger with fake news about a supposed migrant invasion, a “caravan” threatening the southern border;

- They have been helped by the rise in social media over the past two decades; as noted by Claudia Alvares, professor at Lusofonia University Lisbon, “social media are very permeable to the easy spread of emotion”; they are also very permeable to cyber war techniques by the Russians and voter manipulations; the Cambridge Analytica scandal that affected millions of Americans on Facebook is proof.

Populism is on the march everywhere in Europe, notably in Eastern Europe where democracies are new. What is more surprising is to see populists leaders win power in West European countries where nobody expected them to be that successful:

- In Italy, right-wing and left-wing populism came to power together, in May 2018, a historical first and an unlikely alliance, built on the 17 percent won by Matteo Salvini’s extreme right League and the 33 percent won by Luigi Di Maio’s anti-establishment Five Star Movement;

- In Sweden, this summer when the Sweden Democrats, a populist far-right anti-immigration party founded in 1988, with Nazi roots, had its best-ever results:

But the Swedish elections resulted in a deadlock. Indeed, populism’s success has been mixed at best, with some spectacular failures, notably:

- In France, populist leader Marine Le Pen was roundly defeated by Macron, with a party he had founded a year before the elections, La République en Marche;

- In Belgium, the populist Flemish nationalist party Vlaams Belang (reborn from Vlaams Blok that had been condemned for racism in 2004) has been in continuous decline for a decade; in 2014, it lost elections at both the federal and regional level, and got only 5.9% of the Flemish vote;

- In Finland, the populist Finns party (formerly True Finns) which joined Finland’s ruling coalition in 2015 after winning 17.5% of the vote, has imploded and split in two; its two follow-up parties are now polling much lower, at 8.7% and 1.5% respectively;

- In Britain, UKIP after winning Brexit, collapsed, with party membership slumping around 18,000 by January 2018, with only a small uptick (+15%) in July this year after Prime Minister May had the Checkers Agreement published;

- In Denmark, support for the Danish People’s party, a nativist and anti-immigrant party founded in 1995, which lends support to a minority centre-right government, has fallen from 21% in 2015 to 17% today.

Populism is Dangerous: Two Ways to Stop it

Populism is dangerous as has been recently documented on Impakter in a series of articles: (1) it threaten public services, particularly public health (the case in Italy); (2) it mishandles the budget and the economy (again the case in Italy); (3) it demonizes migrants instead of seeking to solve the problem; (4) worse of all, it has a demonstrated propensity for war. All this because populist leaders are far better at manipulating people’s emotions than managing the State.

So far, there are two ways populism can be stopped:

1. The Austrian model: The idea that a moderating center right party can control or at least put the brakes on populism’s worse impulses; Austria is usually taken as an illustration of this approach.

Chancellor Sebastian Kurz’s Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), currently the senior partner in a coalition government with the populist right-wing Freedom Party (FPÖ), personifies the approach. Kurz ran on a “populist light” platform, appropriating many of the right-wing populist tropes, in particular a strong sense of national identity. He also promoted a form of economic liberalism (reassuring to business) and cultural pluralism (appealing to the left).

How well this works remains to be seen.

Macron appears to be following this model, positioning himself further to the right than he had promised when he founded his party. He has pursued a neo-liberal agenda, calling for France to join globalization rather than fight it, a position that de facto promotes big business interests. This has disappointed many people on the left – hence his dropping rate of approval. Macron’s popularity is reaching new lows (below 20 percent) as a “yellow vests” (gilets jaunes”) revolt has erupted this week over new fuel taxes.

In the photo: Protesters wearing yellow vests, a symbol of a French drivers’ protest against higher fuel prices, attend a demonstration at the entrance of a shopping center in Nantes, France, on November 19, 2018. (France 24 news) Credit: Stephane Mahe, Reuters

Likewise in the Netherlands, the more extreme populist impulses have been contained, but at the price of the traditional governing parties moving right of center and embracing many of the populist tropes, particularly anti-immigration. Following elections, a new government was formed in October 2017 with a coalition led by Mr. Rutte, the previous Prime Minister. But he is holding power by just a one-vote margin, giving him little leeway to fight off the extreme-right Party for Freedom, led by the anti-immigrant populist Geert Wilders.

Neither Merkel, Macron or Rutte waited for the advice Hillary Clinton gave this week in an interview with the Guardian, saying “Europe needs to get a handle on migration because that is what lit the flame”, arguing that inflamed voters contributed to Brexit and the election of Trump.

True. But the migrant question has now been addressed by a variety of policies: Policing borders with a strengthened Frontex agency, setting up horrendous detention camps in Libya, slowing emigration from Turkey with a €6 billion deal (already two years old) – precisely what the populists wanted. Regardless of left or right political inclinations, this investigative report from the PBS correspondent in Tripoli can leave no one unmoved :

While the above video is made by an American journalist, European media also often reports on the humanitarian catastrophe in Libya – for example, the Italian magazine Espresso published a special issue attacking Salvini’s anti-migrant policies (17 June 2018) that included a harrowing report on the migrants “locked up” in Libya.

2. The New Left: In Germany, in local elections last month, the Greens, contrary to expectations, roundly defeated the far right populist Alternative for Germany (AfD); this victory marks the arrival on the political scene of a “new left”.

The New Left is pro-European and green. And this New Left is taking votes across the spectrum in Germany, but mostly out of Merkel’s conservative alliance: Alliance 90/the Greens have been recently riding a rising wave of support, winning 18 percent of the votes in Bavaria and 20 percent in Hesse, in practice becoming the country’s second party, while Merkel’s coalition continues to drop. In Baden-Württemberg, they are even the first party. The Greens are in government in 9 out of 16 German states. As a Deutsche Welle journalist commented: Compared to their anti-establishment, radical look when they first entered Parliament in 1983, “the Greens have grown up: They’ve traded in sweaters for slick suits, and eco-radicalism for realpolitik focusing on digital innovation and social cohesion.”

Digital innovation and social cohesion are indeed a radical departure. The German Greens have gone far beyond their initial focus on ecology. As the New York Times recently put it: “Voters, especially urban and educated Germans, relate to the Greens because the party represents a gentrified lifestyle, from healthy eating to a certain self-image of liberal nonconformism, that was once considered niche but has become mainstream well beyond the Greens’ core electorate.” In short, “liberal nonconformism” has gone mainstream, and that’s huge.

In France, the left is also changing, shedding its old skin. The old Communist Jean Luc Mélanchon tried to revamp his party a year before the 2017 presidential elections calling it La France Insoumise but although he got nearly 20% of the vote, it was not enough and he didn’t make it to the final round. Another effort to revamp the left was made in July 2017 by the socialist Benoit Hamon, founding a new movement called génération.s. By January 2018, it had 50,000 members and announced that a European-wide list for the May 2019 European Parliament elections would be prepared.

But revamping the old left, as it turns out, is not enough. Earlier this month, some members of générations.s defected and founded a party of their own called “La Place publique”, further to Hamon’s left and clearly anti-establishment – but pro-European and green.

What is remarkable about the Place publique founders is that they are entirely new faces. They are young, close to millennials, and unlike Hamon (a professional politician who joined the Socialist party in 1988 and has held several ministerial posts), they are not politicians and have never held a government job. But they are experienced activists, essayists or economists, notably:

- Claire Nouvion, the founder of BLOOM, a NGO that has successfully fought corporate private interests and the European Commission in the area of fishing;

- Raphael Glucksmann, a militant documentary filmmaker (notably on the Rwanda genocide and the Maidan revolution in Ukraine) and essayist with a just published book, “Les Enfants du Vide” (Children of the Void) that has become an instant bestseller in France; and

- Thomas Porcher, a member of the academic collective Les Économistes atterrés (they have a striking manifesto that opposes “the neoliberal orthodoxy”).

In the photo: The founders of Place Publique. Clockwise, from left to right: Thomas Porcher, Jo Spiegel, Raphael Glucksmann, Diana Filippova, Claire Nouvion. Credit: article on France 24 Video can be seen here.

Two weeks after its founding, the party had more than 12,000 members. The excitement was palpable at their first meeting last Thursday in Montreuil, near Paris, attended by 1000 members. But, as noted by France 24 in its report, “it remains to be seen whether they will find supporters beyond their natural audience [which is] very predominantly white, young, educated and urban…The leaders of this citizens’ movement must now convince the less privileged.”

For now, the movement is not politically ambitious, it has no list for the next European parliament elections. As Glucksmann explained in an interview on Mediapart (14 November), Place publique is conceived as a place to debate ideas and not a party with an organized hierarchy. The hope is to revitalize the Left with new ideas and a renewed sense of urgency. The way they present their party on the web is striking, very emotional (even if you don’t know French):

France is not alone in rethinking the Left. In Italy too, Carlo Calenda, a businessman and former minister for Economic Development in the past PD governments of Renzi and Gentiloni, published a manifesto in June 2018, to revamp the left. His proposals, very similar to Glucksmann’s, aim to keep Italy firmly in the European Union but reforming both Italy and the European Union to ensure a healthy economy with strengthened public services that meet citizens’ needs (health, education, pension, safety etc).

In the photo: Carlo Calenda with his wife Violante. He stepped out of politics this summer to care for his wife affected by leucemia. Credit: Repubblica.it

This month, Calenda is back in politics and going around Italy presenting his new book “Orizzonti Selvaggi: Capire la Paura e Ritrovare il Coraggio” (Wild Horizons: Understand Fear and Find Courage), also a bestseller like Glucksmann’s book. In it, he expands on his manifesto and provides a critical analysis of the destructive impact of globalization over the past two decades. Whether he manages to take over the old PD and carry out his ideas remains to be seen.

The New Left’s agenda is what makes it radically different compared to the “old” Left. An agenda that shifts the ground under populism. The appeal to emotions is very similar, but the diagnostic of the problems and the solutions proposed are radically different.

The New Left’s Answer to Populism : Neo-Liberalism is the Problem

For the New Left, the culprit is neo-liberalism. Both Glucksmann and Calenda make a clear case that the 1990s globalization carried out under the banner of a neo-liberal or libertarian ideology à la Ayn Rand and embraced by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan is the root cause of all our current economic and ecological ills. If we suffer from income inequality, global warming and predatory big corporations that outsource jobs to save their bottom line and, allied with big finance, stow away their profits in fiscal paradises, it is all due to the neo-liberal order predicated on free markets and free trade.

But the main point is this: Since our problems are global, they need to be addressed at scale. They require global solutions and cannot be dealt with at the national level. The populist argument used ad nauseam by Brexiteers, “ take back our borders”, is pointless, an empty slogan.

Glucksmann is probably one of the better spokesmen for the New Left. We all are, as the title of his book suggests, “the children of the void”. All our political reference points have evaporated, trade unions are disappearing and nothing is left but a deep distrust of the establishment and of historic political parties. And fear. Fear for ourselves, for our jobs that we see at risk from migrants. And resentment of the elites that are exploiting us. He explains this and more in this video (only in French – the book is not yet available in English):

The solutions are simple and all of them global, or at least European-wide. Take climate change. It requires nothing less than full application and indeed, further expansion of the Paris Agreement that is too timid. Or take our economic ills – unemployment, disinvestment, income inequality. They too need to be addressed by strengthened European Union institutions. Austerity policies that strangle small business and employment must be abandoned. The European Union needs to be freed from the neo-liberal ideology and private interests that hold it hostage.

The Euro cannot be allowed to die, it needs to become the world’s second reference currency after the dollar. For this to happen, European countries suffering from economic slowdown need to be able to raise capital to relaunch their economy at less than the current prohibitive cost they now face. A case in point: Italy with its bonds suffering from a widening “spread” compared to equivalent German bonds. The solution is European bonds. That means the European Central Bank must play its role in full and be restructured like the American Federal Reserve backed by a federal treasury. And a clear mandate to fight not just inflation (the case now), but also deflation and unemployment. The point is to sustain growth – not any growth, but sustainable, eco-friendly growth.

Nothing less will work to save the Euro and Europe. The alternative, the “Europe of Nations” propounded by the populists, would open up Europe to the Chinese, giving them the run of Eurasia, and Africa too. Will America remain on the sidelines?

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM COVER PHOTO CREDIT: jeangui111