People who hold to the “Great Replacement Theory”that Jews and Liberals are stirring up People of Color to overthrow White people fill us with so much scorn that, in demonizing them for demonizing us, we become part of the problem. In our increasingly diverse and multi-cultural America, can we find the trust we need to work together?

One of the pleasures of retirement is having an hour to sit down with the New York Times and a cup of coffee first thing in the morning. Sadly, the apocalyptically bad news we have been treated to lately leaves me shaken with horror at the evil loose in the world rather than well-informed and ready to start my day.

I know, I know, even the Good Grey Lady adheres to the journalistic precept that “if it bleeds, it leads.” Nevertheless, I find it hard to deal with my feelings after she greets me every single day with headlines screaming MURDER! MAYHEM! PANDEMIC! SPECIES EXTINCTION! MONKEYPOX!

As my fellow New York Times readers can attest, the murder and mayhem motif often pervades an entire issue of the paper.

That is why on May 16, the Monday after an especially horrific weekend massacre of Black shoppers by an 18-year-old under the influence of “Replacement Theory,” my gloom was (ever so slightly) lifted by two other articles in the issue, one about Scorn and the other about Trust.

The “Great Replacement theory”: How it came about, what it is

Replacement “theory” is an illogical medley of eugenics, race hatred, and White supremacy that has been pervasive in America from slavery times to the present.

After the First World War, Black veterans (many still in uniform) were brutally tortured and lynched simply for having served in the army. Whites feared that having been trained to fight, they would unite to overthrow White “civilization.”

Between the wars, all attempts at anti-lynching legislation were fiercely resisted by Congress, with President Roosevelt consistently withholding his support because he needed to placate White southern Democrats. It wasn’t until this year, on March 29, that the Emmet Till Antilynching Act, named for a 14-year-old brutally murdered in 1955, was finally signed into law.

American aviation hero Charles Lindbergh, an America Firster and Nazi sympathizer, was an enthusiastic supporter of the eugenics theory that considers genetics an indicator of human worth, with the White race inherently superior to all others.

Hitler was encouraged by the idea that “Race mingling” and immigration were undermining the “Aryan” race; he used eugenics as an anti-Semitic dog-whistle to persuade German citizens that Jews were plotting to “replace” them.

Replacement theory feeds on the long-held philosophy of Western dualism which accepts an existential polarity in all phenomena. The statement underpinning the notion of “replacement” – if People of Color gain something, Whites will automatically lose it – is a fallacy because it derives from a win/lose dualism rather than win/win assumption.

Its corollary – that power always means power/over and never power/with – arouses fear among Whites that, if you let Black and Brown people win elections, they will inevitably treat White people with the same kind of viciousness that White people have historically inflicted on them.

Scorn as a reaction: Why it is a “toxic form of polarization”

You can understand why, having listened to Republican Senators and Representatives and neo-fascist pundits like Tucker Carlson raving about Replacement Theory, I want to heap my (elite, liberal) scorn upon them all.

When I read Anglican Priest Tish Harrison Warren’s editorial that “America has a Scorn Problem” in the same issue, I realized that my loathing for Republicans and their allies was part of the problem.

Rev. Warren writes about a “toxic form of polarization” characterized by “a basic abhorrence for their opponents – an ‘othering’ in which a group conceives of its opponents as wholly alien in every way.” She’s right: if I consider Fox News pundit Tucker Carlson abhorrent as a human being, I am complicit in the polarization, and hence deterioration of American democracy: “Too often we find people with different opinions not just wrong, but bad,” with the result that “this hatred toward our opponents and the accompanying habit of moralism is destroying us as a people.”

Though my feelings about Tucker Carlson arise from my most deeply held moral values, in scorning him and his values, am I knocking myself off my own higher moral ground?

One of my basic principles is to honor the dignity and worth of every individual, which has to include Republican Party members and the people they stir up.

To honor anyone, I must understand them: in this case, I need to figure out what are they so angry about? The angry people I know are often reacting to some kind of unconscious fear or grief. Or, as Black American writer James Baldwin puts it in The Fire Next Time, “I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain.”

I am so intensively introspective (I have kept a diary since I was 8 years old and have benefited from 30 years of talk therapy) that it is hard for me to accept the fact that most people entirely avoid probing the sources of their emotions; they feel vague emanations of resentment and anguish, but they do not know why these emotions set them off.

As psychoanalyst Carl Jung puts it, “If we remember that there are many people who understand nothing at all about themselves, we shall be less surprised at the realization that there are also people who are utterly unaware of their actual conflicts.” (quoted from New Paths in Psychology)

What are adherents to American neo-fascism, White Supremacy, and conspiracy “theories” like QAnon and Replacement so afraid of?

With the historical shift in the American White population from majority to minority, White people fear a loss of power which they are convinced will lead to racial subjugation (see my Impakter article on The Tyranny of Merit).

What are they grieving? They are grieving not only power and supremacy but normativity, the security of knowing that it is your norms and values, not anybody else’s, that determine civic and cultural life. Amid such existential polarization, how can we enact our commonality?

America’s broken culture of trust

Had I not come across a third article in my paper, my morning read might have left me completely demoralized. Damien Cave, in his analysis of Australian vs. American Covid death rates, suggests that our American problem is one of trust: simply put, we don’t trust each other, our science, or our institutions.

“When the pandemic began, 76 percent of Australians said they trusted the health care system (compared with around 34 percent of Americans), and 93 percent of Australians reported being able to get support in times of crisis from people living outside their household.”

Former President Donald Trump and his party insisted that science could not be trusted: forget about covid, forget about masks and vaccinations -inject your intestines with bleach and you would be just fine.

Worst of all, Trump cast aside a detailed plan for just such a pandemic that had been painstakingly assembled by the Obama administration because President Obama was a bi-racial liberal with an elitist education, which made everything he did and said a lie.

Although I have no doubt that the profit-based and poorly organized health system in the United States contributed significantly to the different effects Covid had on our population, Damien argues that it is their belief in the common good that saved so many Australians and that its lack in America sent over one million Americans to their unnecessary deaths.

“When Australians are asked why they accepted the country’s many lockdowns, its once-closed international and state borders, its quarantine rules, and then its vaccine mandates for certain professions or restaurants and large events, they tend to voice a version of the same response: It’s not just about me.” (italics mine)

Australians’ ability to act on each other’s behalf is admirable, but our diversity puts America in a somewhat different position. While we are a fully multi-cultural people, Australia has a larger (and stable) component ( 76%) that identifies as White or European; moreover, it is only beginning to experience now the impact of immigration they have long resisted. Until recently their relatively homogenous culture – and disregard for its aboriginal legacy – has no doubt made it easier for Australians to hold values in common than for Americans that have a far more diverse society.

According to the 2020 census, the United States is now 57.3% White, with the rest Hispanic, Black, Asian, and Native American. The trend is towards even greater “minority” population, likely to outnumber Whites in the next decade.

The good news amid this pronounced population shift is that our civic culture – our Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Rule of Law, provides a basis for consensus in diversity.

Perennially endangered by our narrow-minded tribalism and hyper-individualism, we have historically contracted for a pluralistic, big-tent democracy. Nonetheless, there is no question that the scorn we need to transcend and the trust we need to develop will be a much more complex and difficult achievement than in a country like Australia.

Solutions: Non-Violence in Action and Discourse

In our scorn-ridden nation riven by partisan and tribal enmity, how can we possibly effect a common good? The first thing is to recognize that, not just morally but tactically, scorn doesn’t work: it merely leads to more divisiveness, less consensus, and paralytic inaction.

The non-violent strategy developed by Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King remains an effective tool for social change. Though known as “passive resistance,” non-violence is a tough-minded strategy that requires courage, persistence, and tactical wiliness.

In the Civil Rights Movement, the non-violence practiced by huge marches of men, women, and children attacked by police with fire hoses and dogs had a tremendous appeal to the conscience of the rest of the country, as we watched the whole thing on television.

In our present situation, verbal non-violence (which we could also term verbal non-scorning) is effective in conversing with people you (violently) disagree with. Respectful and open-minded bipartisan dialogue is a key tactic in an environmental organization I work with, the Citizens’ Climate Lobby. (see my Impakter article, Making Political Sausage).

One of the most delightful moments in my life as a political activist was watching our Conservative Republican Congressman open up during more than two years of conversation until, eventually, he did what we (respectfully) asked.

This shift from scorn to trust is extremely difficult to achieve and requires lots of practice, which is why organizations like Braver Angels have devised ways to get people who would ordinarily express nothing but scorn towards each other into debates and discussions based on respect for their mutual humanity. Here is what they teach:

- “Skills for bridging the divide workshops help you through difficult political conversations with people in your life; learn how to talk across the divide in a constructive, empathetic way:

- Depolarizing within workshops teaches participants to look within and develop strategies for engaging in politics without demonizing, and how to constructively intervene in social conversations with like-minded peers;

- Families and politics workshops show participants how to talk about politics with their loved ones in a way that brings us closer together — not farther apart;

- Skills for social media e-course shows participants how to share and discuss political viewpoints without contributing to polarization.”

The Miracle of Diversity: Economically viable and culturally enriching

A few days after the May 16 issue of the New York Times, there was a front-page article about an out-and-out diversity miracle.

In “Scarred by a Racist Past, a Georgia County Booms,” Jonathan Weisman describes Forsyth County, which has a long history of lynching and intimidating Blacks: “The people who drove Forsyth’s Black residents from their homes and farms had no name for their hatred, no ‘Great Replacement’ or ‘White Genocide” theories, but the notion that other races were plotting to ‘replace’ the white inhabitants took murderous form more than a century ago.”

Miracle of miracles, when the diverse populations of nearby Fulton County finally overflowed into Forsyth in the 1990s, bringing not only Blacks but also Asians, Asian Indians, Hispanics (and, lately, Ukrainians), the economy boomed, leaving White Forsyth real estate saleswoman Maria Zaragoza declaring that “diversity can never be bad in my book.”

Diversity is inevitable, economically viable, and, if you just open your mind to how interesting other people are, profoundly moving and, actually, enjoyable. Best of all, promoting diversity engages us in promoting our basic American values – let’s go for it!

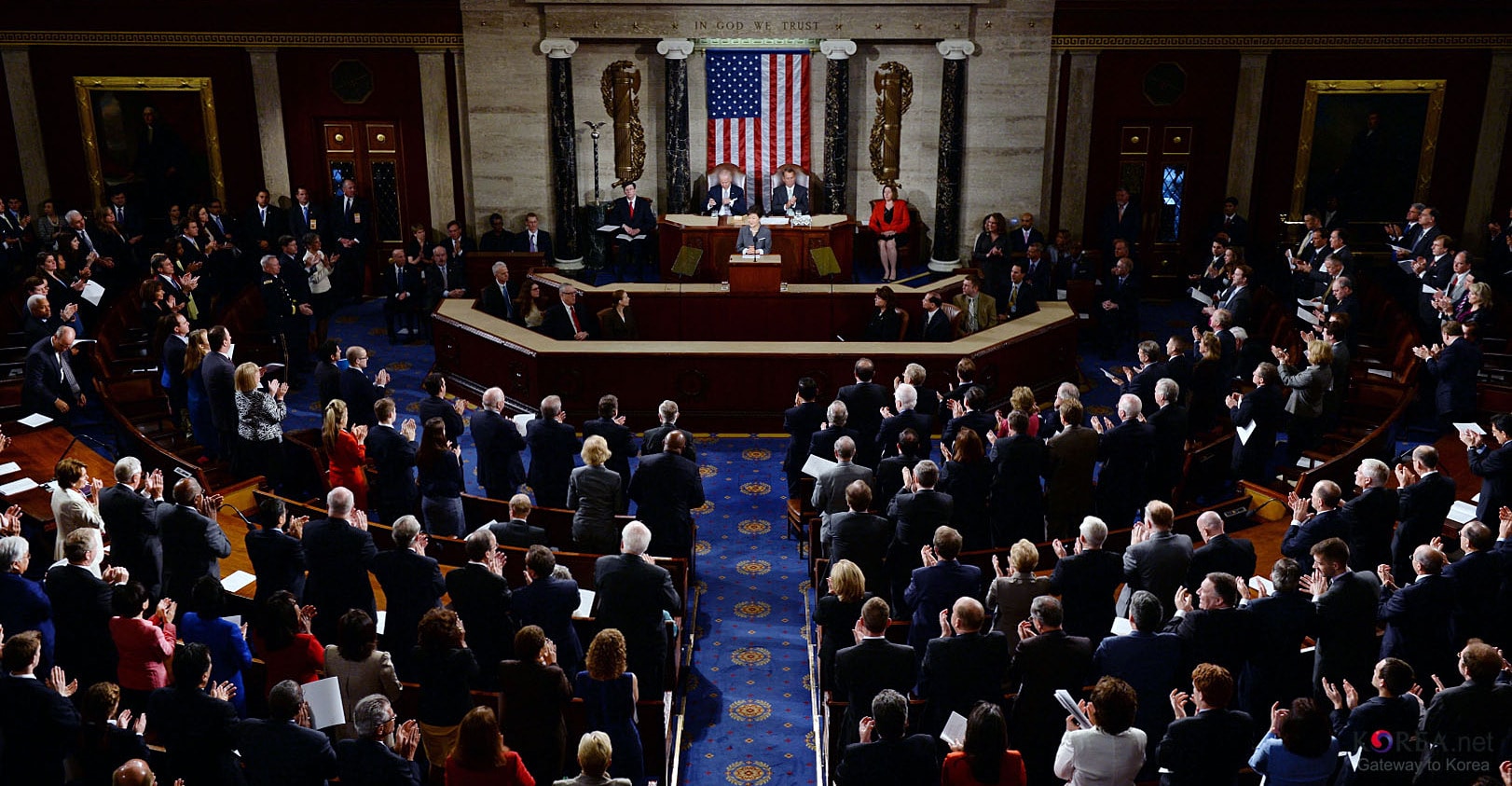

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com –In the Featured Photo: Civil Rights march on Washington, Sept. 2, 2003 Credit: U.S. National Archives