The ozone layer is on track to recover to pre-1980 levels within four decades, according to the Montreal Protocol’s Scientific Assessment Panel.

On Monday, the group presented their findings at the 103rd meeting of the American Meteorological Society. This is an unparalleled win for the environment, with the restoration of the ozone layer helping to avert climate change by as much as 0.5-1 °C by the end of the century, according to their 2022 quadrennial assessment report.

The ozone layer’s recovery, a result of the Montreal Protocol and its subsequent amendments, also confirms the critical role international treaties play in driving change on the global level.

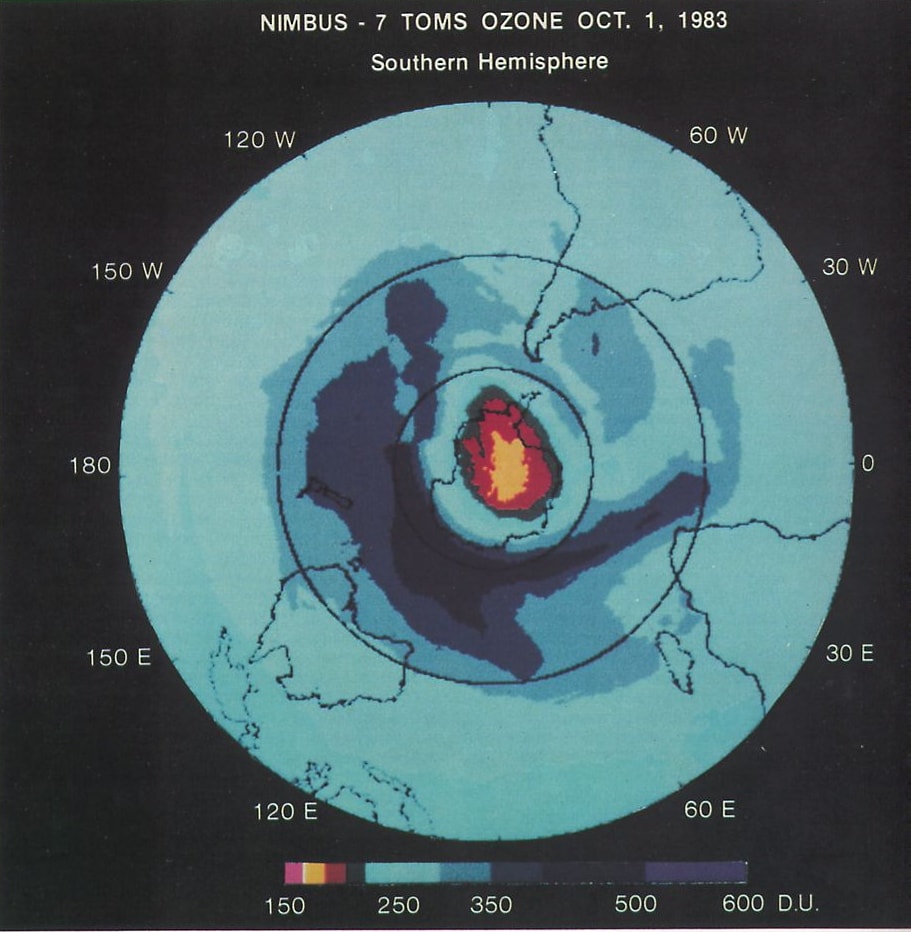

TCO is expected to return to 1980 values around 2066 in the Antarctic, around 2045 in the Arctic, and around 2040 for the rest of the world.

The amount of atmospheric ozone in a given column, measured as total column ozone (TCO), is recovering in the Arctic as a whole, despite considerable interannual variation in size, strength, and longevity of the ozone hole.

The report does, however, have concerns about what might impede this process.

Good news from #AMS2023: The ozone layer is on track to recover within four decades.

Press release ➡️ https://t.co/htPbNDJ9VU

Executive summary ➡️ https://t.co/yO6o2dVOd3

Partners 🤝🏽 @UNEP, @NOAA, @NASA, @EU_Commission pic.twitter.com/03FY2TQHPo

— World Meteorological Organization (@WMO) January 9, 2023

Why is the ozone layer important?

Ozone depletion was first discovered in the early 1970s, when American chemists F. Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina theorised that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) combine with solar radiation and decompose in the stratosphere, releasing chlorine and chlorine monoxide that destroy large amounts of the ozone layer.

In 1985, Shanklin was compiling a backlog of data for the British Antarctic Survey. In response to concerns about spray cans and exhaust from concord destroying the ozone layer, he compared ozone density from 1985 to data from a couple of decades earlier.

To his surprise, there was a significant depletion over the Antarctic. Studying data from intervening years, to see if this was a one-off, he discovered that since the late 1970s, there had been a systematic decline of spring ozone.

By 1984, the ozone layer in the Arctic had lost over 33% of its mass.

This was a result of the ozone hole, a region of especially depleted ozone in the Antarctic Stratosphere that occurs at the start of spring (August-October) every year. The hole has expanded rapidly in area and depth through the early 1990s, with the deepest ozone layer hole occurring in 1994, and the largest area in 2006.

The ozone layer plays two important roles in the Earth’s ecosystem. It absorbs solar ultraviolet radiation (UV), which heats the stratosphere. Increased UV exposure can lead to harmful health effects for humans and marine life.

In addition, the ozone absorbs infrared radiation from the earth, trapping heat in the troposphere. Major ozone losses in the lower stratosphere have had a cooling effect on the earth’s surface.

However, excess ozone is estimated to have been caused in the troposphere, warming the Earth’s surface.

The Montreal Protocol and its success

The landmark accord was signed in 1987, only two years after Jonathan Shanklin published his finding of the ozone hole in the Antarctic in Nature.

Since then, the treaty has grown from 46 to 197 signatories, and is widely considered one of the most successful instances of inter-governmental cooperation to fight climate change.

The Montreal Protocol aimed to control and reduce the amount of ozone depleting substances (ODSs) produced and consumed worldwide, to help the ozone layer recover. As the UN explains, all parties under the treaty “have specific responsibilities related to the phase out of the different groups of ODS, control of ODS trade, annual reporting of data, national licensing systems to control ODS imports and exports, and other matters.”

A key group of ODSs that the Montreal Protocol sought to control and reduce was the global production of CFCs, which were initially used as effective refrigerants and compressants for aerosols, from hairspray to fire extinguishers.

CFCs were popular because of their high boiling point and low reactivity, compared to chemicals used for similar purposes. However, their low reactivity causes them to have a long atmospheric lifetime of around 55 years, in which they continue to deplete ozone.

CFC reduction has been remarkably successful, and the protocol’s scientific panel now confirms, 99% of ODSs have successfully been phased out.

The scientists theorise that some of these unidentified ODSs “likely leaks of food stocks or by-products, and the rest are not understood.”

Related articles: Half of World’s Glaciers Set to Disappear by 2100 – and That’s Probably the Best Case Scenario | EU Takes Action on Forever Chemicals, But Will It Be Enough? | Three-Quarters of World Governments Fail to Provide Transparent Data on Air Pollution | How Air Conditioning Impacts Climate Change: Be Mindful of How You Use It

In 2016, the Kigari Amendment included the phase down of several hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) that were introduced to replace CFCs. HFCs are part of a group of fluorinated greenhouse gases (F-gases), which are not ozone-depleting themselves, but are greenhouse gases that contribute considerably to the “greenhouse effect”.

HFCs grew in use by 70% in the EU between 1990 and 2014, and accounted for about 3% of all greenhouse gas emissions, and accounted for 90% of F-gas emissions in 2020.

The EU aims is well on track to meet its Kigali agreement responsibilities to reduce its HFC emissions to 15% of its 2019 emissions by 2036. In 2021, the EU’s HFC consumption was 60% below the Montreal protocol target.

Targets are set into three groups. The first group, of older industrialised nations, which includes the EU, are expected to reduce HFC emissions by 85% by 2036. The second group of countries, including China and Brazil, 80% by 2045. The final group has until 2047 to reduce its HFC emissions by 80%.

Concerns and past problems

In the 2018 report, the ozone layer did not recover as fast as expected, due to an unexpected increase in CFCs being used. As the first known violation of the Montreal Protocol, the Environmental Investigations Agency (EIA) traced significant CFC use back to China.

Although the substance had been officially banned in 2010, the ban was poorly enforced, and CFC-11 remained a popular “blowing agent” for polyurethane foam, used for insulation in homes, due to its efficacy and low cost.

Following the EIA’s investigation, China cracked down on the use of CFC-11, and its CFC emissions consequently fell.

However, a 2022 follow-up study by the US’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2022 found that China had only accounted for 40-60% of unexpected CFC emissions, finding two other hotspots over temperate western Asia and tropical Asia between 2012 and 2017, although these have not been linked back to any specific governments.

The quadrennial report addresses the “unexpected CFC-11 emissions” in China, stating that “substantial emissions reductions” followed the discovery of “the source region for at least half of” the global unexpected CFC-11 emissions.

Concerning the other two hotspots, immediate action is unlikely, due to the lack of sampling in Africa, Asia, and South America. As the report explains, “[u]ncertainties in emissions from banks and gaps in the observing network are too large to determine whether all unexpected emissions have ceased.”

Although the ozone layer’s recovery is progressing, there is a considerable difference between the upper and lower stratospheres outside of the polar regions. While the upper stratosphere ozone levels are recovering worldwide, the lower stratosphere is not showing the same signs.

The models simulate a small recovery in the mid-latitude lower-stratospheric ozone in both hemispheres that is not reflected in observations. “Reconciling this discrepancy is key to ensuring a full understanding of ozone recovery,” the study states.

The study does state further worries about the continuing health of the ozone layer. Several space-borne instruments that the group uses to measure ozone health are due to be retired in the next few years, without which the group will struggle to monitor and explain ozone activity.

Their “heightened concerns” include further increases in nitrous oxide, methane, and carbon dioxide concentrations; rapidly expanding ODS and HFC feedstock use and emission; and the increased frequency of civilian rocket launches and the emissions of a proposed new fleet of supersonic commercial aircrafts.

Although restoring the ozone layer will help with climate change, climate change itself can have devastating consequences on the ozone layer, which will impede its ability to recover.

The 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption, for example, caused the Antarctic ozone hole to grow to unprecedented size in 1992. The study reports extraordinary wildfires and volcanic eruptions as significant concerns to the ozone layer going forward.

Overall, the study is positive about the progress of the ozone layer, which is on track to recover. Beyond the effects on the ozone layer itself, the success of the Montreal Protocol is a fantastic example for climate science being reflected in global policy.

However, now is not the time to rest. Going forward, the ozone layer needs continued monitoring, and the Montreal Protocol must remain in effect if we hope to achieve 1980 ozone levels at the projected time.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Earth from space. Featured Photo Credit: NASA.