The concept of One Health – the intersection of animal, human, and the environment – has been around for some time. Recently, it has taken on heightened interest because in addition to the worldwide COVID pandemic which has dominated lives everywhere, there is now a global outbreak of Monkeypox which, on July 23 this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).

Looming next is concern about the Langya henipavirus, each being of animal origin and transmitted to humans.

Both cases underscore the need for a One Health approach that broadens disease surveillance beyond the human to cover the zoonotic sphere. And marshaling the knowledge and technical know-how found in veterinary practice as well as calling on other disciplines to better address the disease.

How the One Health approach is a game-changer: The case of Monkeypox

Monkeypox, a much less dangerous relative of smallpox, is an example of why such an approach is essential. Various animal species have been identified as susceptible to the monkeypox virus. This includes rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, dormice, non-human primates, and other species.

Uncertainty still remains on the natural history of the monkeypox virus and further studies are needed to identify the exact reservoir(s) and how virus circulation is maintained in nature. And this is where in the future, a generalized adoption of the One Health approach could make the difference as it encourages more research focused on the natural world.

That said, monkeypox is relatively well known and Africa has been dealing with outbreaks of monkeypox since the 1970s, in the forested parts of Central and West Africa, after an interaction with an infected animal.

However, the current concentration of cases is mostly in Europe and North America with the recent outbreak most likely starting in the United Kingdom in May 2022. At the time of writing, as monkeypox cases reach over 7,500 in the US, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has issued new guidance:

This is a stark reminder that we need a One Health pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response system for surveillance and monitoring to detect and respond to outbreaks quickly.

Adoption of the One Health approach around the world: Where we stand today

What may be gaining significant traction at the global level, at the country level, and with advocacy organizations, is that a One Health approach is critical to our collective future wellbeing. Whether this is a sustained engagement is yet to be determined.

At global level

The COVID pandemic has brought to the fore the real-life implications of diseases originating in animals that explode as deadly for humans, everywhere in the twenty-first century.

Last year there were extensive discussions and decisions on One Health by the G7 and G20. Subsequently, consultations among four critical technical UN entities, namely WHO, FAO, WOAH, and UNEP, resulted in a joint report, importantly providing a common One Health definition, and much more.

Further, the May 2022 World Health Assembly approved a process to develop a Pandemic Treaty, the impetus being widespread dissatisfaction with an existing instrument, the International Health Regulations (IHR). In theory, it has all the “right stuff” but in practice has been unable to deal in a timely manner with outbreaks principally because of enforcement limitations.

In this regard, some argue that the way to put in place a universal instrument will require United Nations General Assembly engagement.

In terms of new donor engagement, the World Bank is in the process of developing the rules for a new multi-donor financing initiative, the Financial Intermediary Fund for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response (FIF PPR). If this new mechanism is to achieve its transformative promise of making the world safer from pandemics, it must include options for significant One health funding.

While these measures do not assure continued and sustained attention and resources for One Health, cumulatively they represent far more high-level engagement than ever before and cause for modest optimism.

At country level

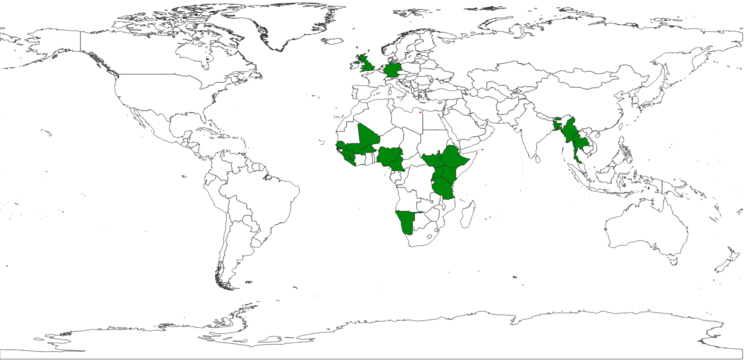

Of great significance is the growing number of countries adopting One Health Strategic Action Plans. The One Health Commission provided a useful compilation of available information, which is to be found on its website (here) and it has begun to put together a world map showing where such Actions Plans have been launched:

In some instances, such “plans” have remained at this point simply that – a proposed list of measures still to be implemented.

However, in other cases, it has meant not only adoption of a strategy but doing more, including estimating investment benefits compared to costs, as was done in Cameroon.

A study from 2021-2022 looked at Cameroonian cost-benefit resulting from the 2016 Avian Influenza (HPAI H5N1) outbreak and the response. It found that for every $1.55 invested during 2016 the return on investment was $4.65. This rate of return continued and implied concrete benefits:

a) 700.000 direct and indirect jobs related to the poultry sector were preserved,

b) as a result, the poultry sector was found to contribute 4% to the GDP, and

c) widespread availability of chicken which is a primary source of animal protein.

Non-governmental engagement

One could legitimately argue that it has been the persistence and perseverance of many individuals, non-governmental organizations, and others that have made all the difference.

While too many to mention, included in any such list would be the One Health Initiative, the One Health Trust, the 1HOPE initiative, and the One Health Commission referred to above, research entities such as the EcoHealth Alliance, and universities such as the University of Edinburgh (UK), of Bielefeld (Germany), of Belgrade (Serbia), of Pretoria (South Africa), of Kentucky, and many more.

Numerous articles and editorials in peer-reviewed journals, such as the Frontiers in Public Health by Professor Ulrich Laaser, contribute to a better understanding of the relevance of One Health.

Such efforts have led to a much-strengthened evidence base and support within the public and private sectors and with communities.

The case for making One Health a priority – what happens next

Rarely do major global or local concerns make progress in a linear fashion. We know, for instance, that commitments to reduce reliance on conventional energy have gotten sidetracked as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Further, as the world has become more polarized, prospects for global cooperation have diminished with nearly everything seen from the political optic.

Coupled with this environment is the fact the number of cross-cutting issues is now very large, such that a newcomer will have to fight hard to gain focus at the global, country, and community levels.

That said, the case for One Health making it a high priority is compelling. We know that the likelihood of another virus threat beyond Monkeypox is not that it might “possibly” happen or “whether” it happens, but when and where it will begin. It will not be easy, but necessary.

Let us hope that the momentum now existing for One Health does not diminish but rather grows exponentially.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Monkeypox virus (cell) Related to smallpox, it is usually milder, particularly the West African strain of the virus that was identified in the US, which has a fatality rate of around 1 percent. Most people fully recover in two to four weeks. The virus is not as easily transmitted as the SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused the global COVID-19 pandemic since it seems transmitted through contacts of skin affected by rashes and not through the respiratory route which makes COVID so infectious. (May 23, 2022) Source: Brooklyn Camrin Flickr (cc)