We have been experiencing the worst global pandemic in over a century and it has brought the world economy to its knees. Now we need to map out the path to recovery, and in doing so, we have become aware of the incredible challenge of how to do better in the future. A lot will need to change for our post-COVID world to be sustainable and protected from another pandemic hitting us through an animal vector. In this article, I explore the most important change that needs to be made and that involves addressing 21st Century education challenges in a One Health manner.

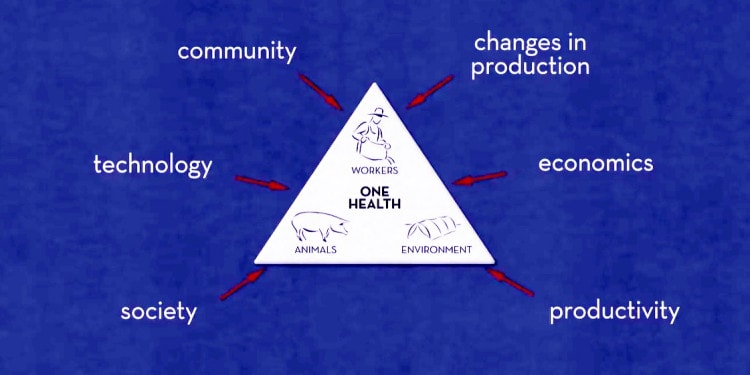

The starting point is for us to recognize that the interface between animal-human-environmental health is not rhetoric but reality. The concept of One Health, which once sat on the periphery of the academic world, has now taken full center. This means that civil society, political decision processes, and the private sector need to embrace this fundamental notion.

For this to happen there needs to be a pathway to support education as both learning and teaching should encompass the One Health concept. And that is the genesis of the One Health for One Planet Education (1HOPE) Initiative, launched in April 2019, a year before the onset of the pandemic. The 1HOPE Initiative, as it says on its website, aims to “build and support global capacity for understanding” the One Health concept “as the foundation for achieving the UN-2030 Sustainable Development Goals”. To build that capacity is the very objective of the learning modules contained in The Special Volume 2021 of the South Eastern European Journal of Public Health (SEEJPH), with the title: The Global One Health Environment.

What Is One Health and Why it Matters in Education

The One Health notion was already in the writings of two major thinkers of Ancient Greece, the physician Hippocrates and Aristotle. Their classical One Health concept was derived originally from increasing concerns about infections through animals.

The One Health ideas of today reflect a more expanded response to the accelerating environmental changes of the past 100 years and the explosive growth of the global human population.

In this 21st century global level we have two major aspirational efforts, namely the seventeen United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, and the Paris Agreement, within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, addressing climate change mitigation, adaptation, and finance.

Both provide a foundation for moving forward with One Health but so far there has not been the expected acceleration or even sufficient focus on the concept.

It is for these reasons that a group of leading medical professionals, development practitioners, sociologists and other experts from around the world contributed to an educational document designed to “support learning and teaching about the environmental status of the planet” and foster “interaction between inclusive governance and environmentalist activities in the community.” As mentioned above, it was recently published (15 March 2021) in the SEEJPH Special Volume 2021, enabling it to reach a broad audience and have multiple uses.

The Challenges Ahead: What Is Needed Is a New Way of Thinking

The learning modules were informed and shaped by the work carried out by Professor Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University that, together with well-known European economists including Mariana Mazzucato, identified six transformations needed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in 2030, as shown in the diagram below:

In our work as we developed the learning modules, we recognized that according to the World in 2050 initiative there were five major challenges embedded in societal structures that will be difficult to change, namely:

- Multidimensional poverty: hunger, malnutrition, deficient healthcare;

- Rising inequalities of material resources and education;

- Environmental degradation;

- Demographic stresses: high fertility, accelerated urbanization, rapid aging;

- Deficits of governance resulting in migration and rising nationalism.

Major resistance points identified are likely to be:

- Vested interests, specifically, owners of fossil fuels, beneficiaries of unsustainable land and ocean practices;

- Major wealth owners avoid taxation;

- Limited capacity of governments to plan and implement policies because of the short political business cycle and the lack of strong planning units supported by universities, and think tanks;

- Difficulty of a suitable balance in public-private partnerships (successful lobbying vs. strangulation of initiative);

- An ill-informed public develops fear and resistance to change leading to ‘status quo biases.’

Put in context, what is needed is an endorsement of the new way of thinking about the planet and each other.

The 21st Century Vision: Work With Nature – Not Against It

We now know that the 20th-century‘ vision’ about how to address infectious diseases was limited: We used to think that it could be primarily dealt with through basic scientific understanding, advanced technology, and unlimited energy. That, of course, resulted in essentially freeing humanity from the bonds of nature. But we have learned as a result of COVID, that we cannot and should not free ourselves from the bonds of nature.

As a result, there are important key questions collected from various experts and sources which now must be considered:

- What socioeconomic and geopolitical changes would be needed to adopt the view that business should serve not dominate our world?

- How to re-conceptualize global priorities, policies, and practice, and needed societal transitions in terms of human behavioral change?

- What might be promising models of change translating into policy outcomes – criteria and strategies?

- What are some of the main obstacles in gaining support at local, national, and regional levels? How might these be addressed?

- To what extent could policymakers learn from each other about the deficits in controlling non-communicable diseases that are made across the world and thus, work towards the development of multi-sectoral and integrated policies?

- How might the ‘One World, One Health’ concept act as a transformative, potentially epoch-defining approach to ensure the future sustainability of life on the planet?

The upshot is that human behavior and society as a whole must be at the center of answers to these core questions, additive to the work and focus on the domains of the natural and life sciences.

The COVID pandemic is making those questions more urgent than ever before. And when there are unexpected deviations from the normal course of the pandemic, experts in a wide range of disciplines, working in a collaborative manner have to be called in to solve the riddle, as is now the case in India:

The challenge for us in the 21st century is to engage in interdisciplinary research programs in a One Health manner to be able to generate evidence for decision-making and prevent future global catastrophes.

Inclusive Governance and Education

Universities have a crucial role to play and need to be supported to provide better education and develop the capacity to support students who will be affected by the impacts of epidemics, climate change, and other environmental challenges affecting human health.

To move to a One Health One Planet orientation will depend on progress on all the Sustainable Development Goals, but especially SDG 3 “Good Health and Wellbeing”; SDG 10 “Reduce Inequalities”; SDG 16 “Promote Peace and End Violence”; and SDG17 “Partnerships for the Goals”.

Given where the global commons is at this point in time, with COVID-19 paramount in public leader thinking, it gave us an opportunity to focus on a learning module dealing with the central issue of “governance”.

International discussion is shifting away from “good” to “inclusive governance”.

While “good governance” is still widely used to assess governance process qualities, such as accountability, transparency, effectiveness, efficiency, it is increasingly recognized as insufficient in guiding public institutions in fulfilling their role in redistributing public goods and fostering equality amongst people.

The 2017 World Bank Report, “Governance and Law” makes the important point that distribution of political power drives institution-building and policy outcomes. To achieve One Health objectives much will depend on the performance of public leaders and institutions, enabled by their education and continuing learning ability.

A lot of effort has been made or planned to be invested in the supply side, even in the public health sector, which up to now is the stepchild of the health services. A recent Impakter article underlined the relevance of the “demand-side” – making the point that much more investment is needed in the social sciences, in understanding human behavior and ways to garner people’s trust in prevention and containment measures in future health crises.

Environmental information is provided in many curricula but often focused on such subjects as microbiology, laboratory medicine, and water quality. No question, these subjects are important. But there are other key questions that need to be addressed: Who is in charge of global coordination and able to do it efficiently? How well adapted to the needs of all social groups are the programmes in our educational systems, from schools to professional training and universities?

Formal education is, of course, the foundation for One Health. It cannot end there but must be supported with robust continuing educational efforts, consistently reaching all levels of the population with thoughtful and appropriate information and messaging.

We need our leaders, universities, youth, and all of civil society to join in common cause to integrate animal human-environmental health in our thinking and actions. This was and is the goal of the “Special Volume 2021: The Global One Health Environment.”

To download the pdf of the article “Special Volume 2021: The Global One Health Environment”, click here.

Richard Seifman contributed to this article.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Diagram explaining One Health concept Featured Photo credit: Upper Midwest Agricultural and Health Center funded by NIOSH