After several years of effort, Pandemic Agreement negotiators deliberating in Geneva at the World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters, were still unable to come to any “final” conclusion. They produced a 100-page draft text, which has not yet been shared publicly. These deliberations will continue until early May 2024, likely with this text drastically shortened, and possibly watered down.

WHO has been the global community guardian of human health for over a century and its core mission, staff composition, and deciding body structure (the World Health Assembly with delegations led by Ministers of Health) are most confident and comfortable in dealing with human health sector matters and approaches.

Recent worldwide experiences with COVID-19, and before that with HIV/AIDS, and Ebola, have garnered significant attention on the need to go beyond human medical matters and integrate multiple sectors.

What has also become clear is the fundamental role of communication outreach to both health and other sector providers and beneficiaries for preventive surveillance, and response. Indeed, as argued in an earlier article, much more focus is needed on the demand side of any infectious disease response, which means effective communications with the beneficiaries and with practitioners.

Given that 60-75% of human infectious diseases have origins in animals, and that we know now how crucial environmental factors are to human, animal, and plant health, it would be misguided not to make effective use of past experience and new knowledge acquired by scientists, policy experts, health practitioners, and communities.

The new outbreaks of Avian Flu are a case in point.

Avian Influenza (HPAI): An emerging threat

As this is written, there is a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak in wild birds and poultry, and it is growing in most corners of the globe.

Current geographical scope:

The present HPAI outbreak has wide geographic reach and varying severity, transcending national borders and regions. For example:

North America

The United States has experienced significant outbreaks in poultry flocks since early 2022, with the virus detected in 48 states (CDC) as well as in Canada, there are reported outbreaks in wild birds and commercial poultry.

Recently HPAI has been detected in dairy cows in five U.S. states, with warnings that their unpasteurized milk can have dangerous microorganisms adverse to human health.

But even more recently and is that there has now been a case of a man in Texas infected with Avian Flu from direct contact with dairy cows.

Europe

Nine European countries have confirmed Avian flu cases, namely, Germany, France, Belgium, Bulgaria, Poland, Slovakia, Sweden, Moldovia, and Hungary. These have been found in commercial poultry farms and captive birds.

Asia

The latest Avian Influenza weekly update shows that Asian HPAI continues to pose a problem in the region. China confirmed a human case in 2023 and more recently, Vietnam and Cambodia have both experienced transmissions to humans.

Vietnamese health officials released a statement on March 25, 2024, stating in part: “Male patient, 21 years old, on March 11, 2024, developed symptoms of fever and cough and self-treated but the symptoms did not improve…. on March 22, 2024, determined that the patient was positive for influenza A(H5N1). Due to the serious progression of the disease, the patient died on March 23, 2024.”

The Vietnam Health Ministry statement goes on to say about its neighboring country, “Cambodia, continued to record cases of influenza A(H5N1) in humans since the end of 2023.”

Africa

Many African countries across the continent have experienced various strains of HPAI. Reported outbreaks in 2024 include confirmed cases in South Africa, Nigeria, and Burkina Faso.

Such widespread geographical distribution raises concerns about the virus’s potential to further disseminate through migratory birds, and how changing weather and water patterns will affect the course and nature of the virus.

Indeed, the current outbreak is likely due to several factors, including increased viral mutations, changes in migratory patterns of wild birds, particularly waterfowl which act as natural reservoirs for influenza viruses, wildlife trade, and environmental change, coupled as well with intensive poultry farming practices.

Related Articles: Why One Health is Key To Address Future Pandemics | Dengue Fever: Not Getting Many Headlines, But It Should | Our Emissions Are Aggravating Over Half of All Infectious Diseases | The Climate Is Changing: What This Means for Our Fight Against Infectious Diseases

Factors that make Avian Flu a potential human pandemic threat

They include:

- Mutations and adaptation: The longer the virus circulates in birds, the higher the chance of mutations that could allow it to infect humans more easily.

- Mixing Vessels: Some mammals, like pigs, and we now know dairy cows, can be infected by avian influenza viruses, serving as “mixing vessels,” where it is possible to exchange genetic material, potentially creating a new strain with pandemic potential.

- Global Spread: With the widening spread of outbreaks, the opportunities for the virus to mutate and adapt could increase human risk, as does wildlife trade, whether as pets or for consumption, which provides another expanded route for transmission.

That said, Avian Flu has not moved to the point of extended transmission to humans such that it would be designated by the 2005 amended International Health Regulations (IHR) a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” (PHEIC). This is a designation likely to be revised in any new Pandemic Agreement.

Global Efforts to Prevent Prepare, and Respond

Self-interest must have us better prioritize the interconnectedness of human, animal, plant, and environmental well-being. Much work has already been done, both in developing the evidence base and in identifying the approach to move forward.

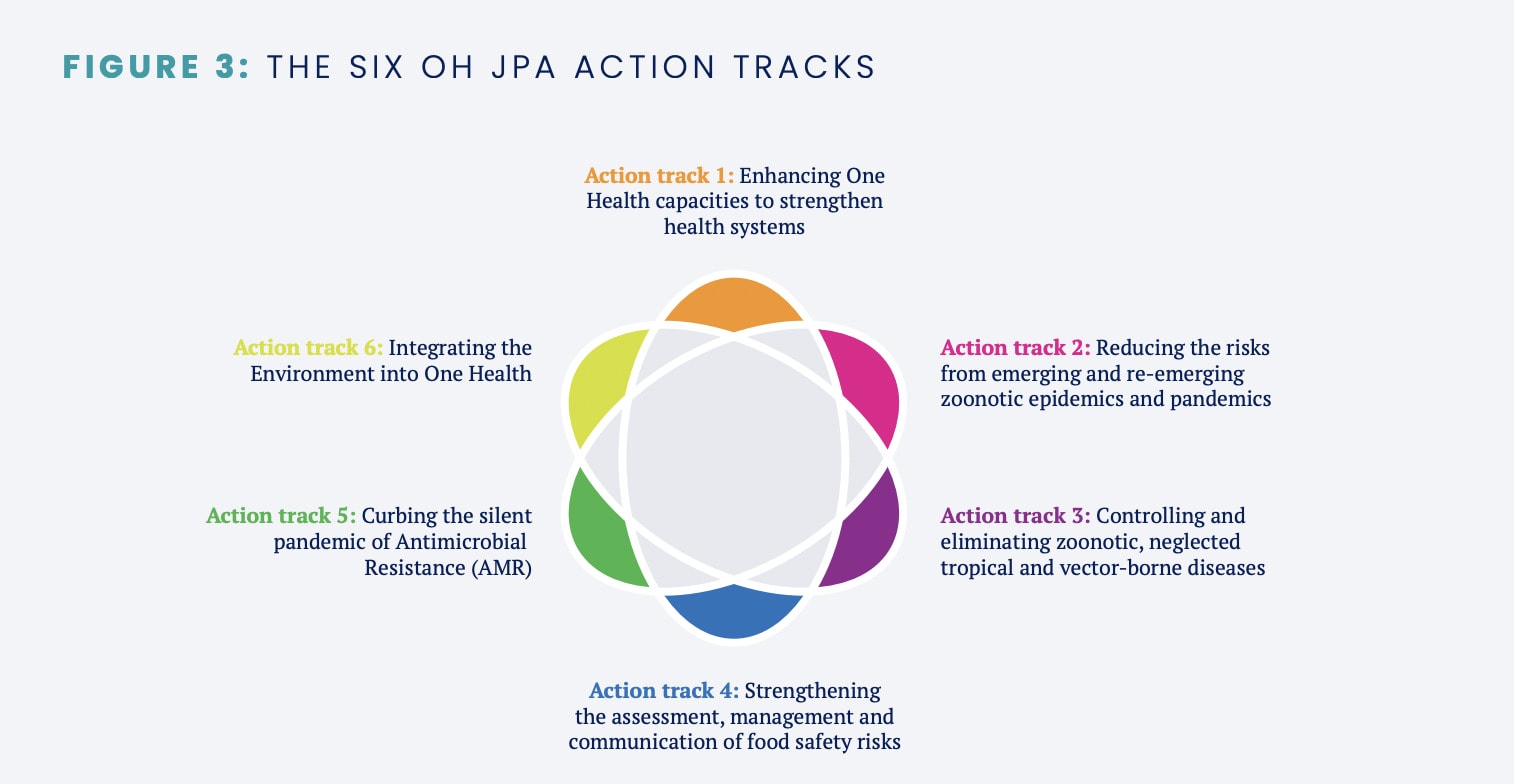

For example, four United Nations agencies have been collaborating for a number of years on this challenge. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Health Organization (WHO) — collectively called the Quadripartite — have looked at ways to drive the change and transformations required to mitigate the impact of current and future health challenges at the interface of humans, animals, plants and the environment, a.k.a. One Health, at global, regional, and country levels.

They developed a One Health Joint Plan of Action with a broad One Health perspective, which identifies and addresses the underlying factors of disease emergence, spread, and persistence, as well as the complex economic, social, and environmental determinants of health.

This Quadripartite Plan of Action plus the considerations in the last Pandemic Agreement draft document that is available to us — including an explicit article on One Health — suggests heightened recognition and attention by countries, regions, international organizations, scientists, civil society, the private sector, and communities to look beyond explicit human medical challenges and underlying root causes.

This may be wishful thinking, but we will know more in the next few months if such apparent awareness is translated into concrete commitment and actions…

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Cover Photo Credit: NIAID.