Two-thirds of the Netherlands’ population, including its capital city of Amsterdam and several other major population centres, lie below sea level.

The country’s low-lying, swampy environment bears witness to the country’s centuries-long battle with water. Canals carried the water away after being pushed out of soggy fields by windmills. Dikes prevented further flooding.

“We are world champions in making land dry,” said Peter van Dijk, a blueberry grower in the Netherlands, noting that we live in accelerating conditions of climate change, marked by extreme weather events.

Global warming means that people are more likely to suffer from droughts and strong rainstorms. Societies like those in the Netherlands must prepare for both extremes.

When even a more developed and wealthy nation like the Netherlands finds it challenging to address climate change-related issues, one may well wonder what options are left open for third world nations far less well-equipped with the means to address the issue.

The Dutch government has tried hiking costs for those who use a lot of water, but it is concerned about blowback. Tighter regulations on building in vulnerable regions may make the housing crunch worse. Water consumption restrictions might cause conflict with farmers who have already opposed a proposal to reduce nitrogen emissions.

Due to its dense population, the Netherlands’ primary drought issue is a lack of area for large reservoirs.

Furthermore, because of the country’s flat territory, in order to move water without the assistance of gravity, pumps must be used and they require a lot of energy.

But the problem is not limited to the Netherlands.

Throughout the continent this year, amid Europe’s record-breaking hot summer, there were wildfires fueled by heat, harvests in danger, and hydroelectric resources were dangerously stretched.

Related articles: Climate Change: the Dutch Solution | Europe’s Worst Drought in at Least 500 Years Continues

Drought conditions extended throughout Europe this summer

According to recent research, the odds of having soil conditions as dry as those in Europe this summer are now at least three times higher than they would be in a world without global warming.

Due to the hot and dry summer, the Rhine River’s inflows decreased. The river feeds from the Alpine snowmelt and supplies the majority of the nation’s fresh water.

Germany’s water discharge into the Rhine in August was at an all-time low and this issue affected the whole region, well beyond German borders.

For example, water in Enschede, a city of 159,000 inhabitants in the Eastern Netherlands was at times so scarce that farmers have turned to illegal sources of water, pumping from ponds at night.

The Enschede water board started issuing warnings and penalties following the illegal sourcing of water incidents in 2018. They’ve allocated personnel to patrol water sources and were contemplating the installation of cameras and sensors.

But the problem goes beyond incidents caused by illegal water pumping. The whole situation had changed and Dutch farmers for the first time found themselves with a new challenge: The need to reverse centuries-old traditions that were aimed to get rid of too much water – for example, by making drainage ditches shallower so that they take less water from the earth.

The Netherlands are redesigning the soil from the ground up in order to retain water

Due to the fact that two-thirds of the Dutch people reside below sea level, droughts may swiftly worsen in the Netherlands, causing rivers to slough off and make water transportation difficult if not impossible.

Drought has now become a recurring problem in the Netherlands and the water management team has been trying to tackle the issue since the early days of the summer.

Enschede city planners have cut indentations into the grass to collect rainfall that would otherwise be washed away through the sewers.

Concrete tiles are being peeled off the ground to reveal a more permeable surface, and indentations into the earth with many bends are being made, slowing the flow of streams and brooks.

Water boards in the country are now urging farmers to keep their soil moist and preserve water by using drip irrigation instead of inefficient spray cannons.

Drought and energy prices that have skyrocketed this year as a result of Russia’s conflict in Ukraine have even led to discussions over whether the nation’s high levels of crop production are sustainable; whether their famous tulips, cheese, meats, fruits and vegetables can continue to be produced at the same levels.

Gertjan Zwolsman, a policy consultant and researcher at Dunea, a drinking-water firm that serves 1.3 million people in and around The Hague, and his colleagues are looking at ways to pump up and treat the brackish water beneath the Netherlands’ sandy coastal dunes.

The procedure consumes a lot of energy. But so does carrying river water across long distances to cities, according to Franca Kramer, a Dunea researcher.

Massive storm barriers or other flood control initiatives haven’t been part of the nation’s drought adaptation strategies, but if the globe warms more than 2 degrees Celsiusin coming years as many predict, Dutch policymakers may need to think about bolder and perhaps riskier actions.

Rotterdam, the biggest port in Europe, is one of the areas that will require special action as climate change accelerates.

Today, the city has an open canal leading to the North Sea that makes it simple for cargo ships to arrive and leave. In order to drive the seawater back out of the channel, the Dutch authorities must pump enormous amounts of fresh water down the river.

As sea levels rise, “you’re going to need more and more water to keep that sea out,” said Niko Wanders, a water expert at Utrecht University. He thinks that someday, like it was done with the Port of Amsterdam, the government will need to use locks to close off the Port of Rotterdam. This would slow down shipment while making water available for other purposes.

Although the Dutch government restricted the number of times the locks near Amsterdam may be opened each day to prevent saltwater penetration during drought periods, it still doesn’t entirely solve the issue.

One of the even more drastic measures that has been suggested is a huge new sea barrier that fully isolates the Dutch shore. It would be expensive.

The alternative, which might cost far more, is to keep altering and adapting water infrastructure for even harsher conditions, according to Stefan Nieuwenhuis, a senior expert for the Dutch water ministry.

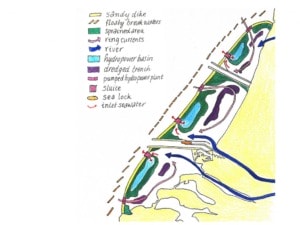

Engineers Rob van den Haak and Dick Butijn designed a plan for a gigantic new sea dike off the shore which would shield the Netherlands, and ideally the rest of Northwest Europe, from rising sea levels for generations to come.

The Dutch have intricate systems and dams to prevent them from flooding. There are already many ways people around the world are adapting to the rising sea levels.

Rotterdam leads the way in flood proofing sea-side towns, as it builds a new environment with low-level squares, underground parking lots with increased water storage capacity, green roofs, and water-absorbing façades — all of this intended to transform the city into a “sponge” in the event of severe rains.

Our planet is progressing despite climate change deniers, and the Dutch are leading the way thanks to a millennium of expertise acquired through battling rising sea waters. How much of their solutions can eventually be replicated elsewhere is open to question – much depends on finance, on the willingness and capacity of people to invest in the necessary infrastructures to protect their future.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: The river IJssel near Zutphen, Netherlands is running dry due to drought.. Featured Photo Credit: Harald/ Flickr.