In a series of four articles, millennial scientist Jesse Zondervan delves into the future of geoscience applications in relation to the rise of globalisation. In this first article, he shares his views on the shift in the global knowledge economy as he asks the questions: who are the scientists of the new generation and what are their values?

As a young geoscientist, I have seen firsthand the increasing role that geoscience plays in shaping the world we live in. From judging earthquake and flooding risk on investment portfolios, to geoengineering the climate, geoscience applications have the power to improve many aspects of the future of our societies. At the same time, the rapid change that brings this power to scientists brings with it certain ethical challenges as well.

Through this series of four articles, I hope to shine light on some of the future challenges that surround science in a rapidly changing world. To set the context, I will consider the place that scientists take in society and how this place shapes their values and interests. In order to predict possible directions science might be moving in, I have set myself a prophetic task, one to which I must lend my imagination, knowledge of geoscience and my millennial world-view.

First of all, other than a geoscientist, I consider myself to be a cosmopolitan. Much like many other young scientists today, I too have migrated to follow my academic interests. From the Netherlands I went to study in London and in Australia, and have then moved to one small, English town. As a consequence, many of my friends today come from all over the globe.

During the process, I have developed an appreciation for the way people, especially educated and skilled people, tend to move and cluster. These are the ideas reflected in the first two sections of this article.

As a millennial, I am part of a generation that is characterised by connecting with people and having a distinct perspective on the world and its place in it. We increasingly tend to connect more with people who harbour similar cultural or spiritual views and values to ourselves – even if they live on the other side of the world – than we do with people who are physically around us.

The combination of globalisation and cultural change in the world-view gives rise to an interesting and powerful way we interact with the earth around us. I foresee that with rampant socio-economic, cultural and technological changes, a new generation of scientists – geographically clustered and socially segregated – appears to be gaining tremendous power to manipulate the physical earth and hence the human interaction with it.

Who are these scientists, where are they and how well-prepared are they for the challenges of today?

The Clustering Force – Where Does The World’s Brain Reside?

The concept of globalisation, being as widely recognised and discussed as it is, has some very clear hype around it. What I have recently come to realise, though, is the extent to which globalisation is not only connecting, but segregating and clustering economic and creative activity in the world by impacting the physical residences of our most successful scientists. But how exactly is globalisation affecting this?

Cities, while only occupying about 2% of the earth’s surface according to the New Urban Agenda presented at the Habitat III conference, contain the majority of almost everything. Economy, global energy consumption, or, for instance, global waste. But these are not just clustering in cities – they’re clustering in certain cities and not in others.

Photo Credit: Habitat III Conference

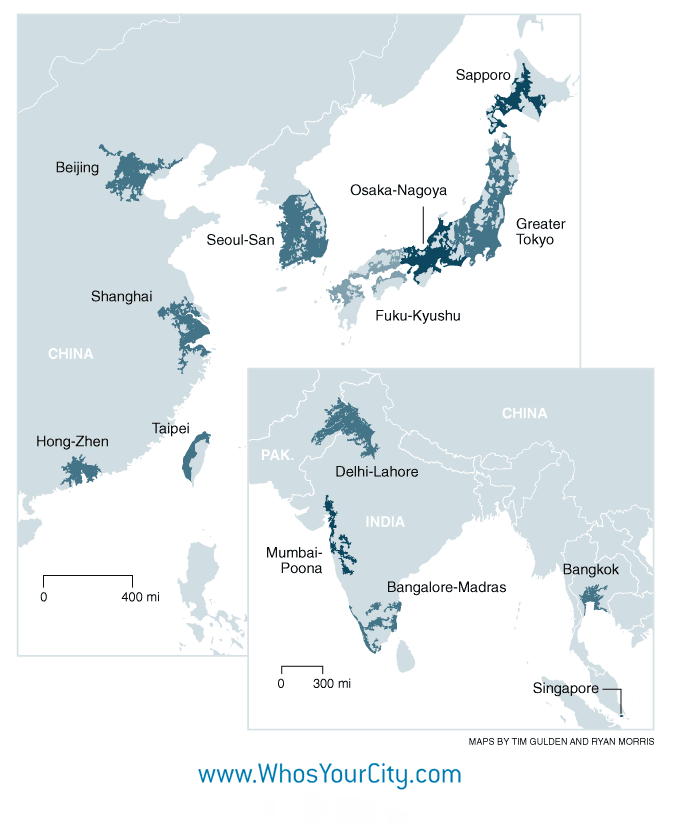

American urban studies theorist Richard Florida published a series of books, including maps, on what he calls the clustering force. The first cluster he considers is that of population, which spikes in cities and certain areas of the world, most notably Europe, the United States, India and South-East Asia.

What’s more interesting is that once you look at his map of economic activity, a lot of the spikes seem to disappear, leaving only the clusters in Europe, the United States, Japan and some parts of China with noticeable spikes. If we were to go further and transcend economic activity, which encompasses any standard industry as well as all creative enterprises, and if we examined innovation, what we would find is that even more of the world falls of the radar, leaving the focus on Japan and on the major European and US cities.

And then we have the star scientists: the most well-connected and well-cited scientists in the world. London and some of the other cities in Europe and in the United States spike high on this map. These are one of the most clustered groups of people you’ll find.

Influence beyond the ivory tower – mega-regions and their backyards

While scientists on one hand cluster in cities, on the other they are becoming increasingly responsible for developing parts of the world that they have little or no direct connection with.

The rise of the cities, so far, has been quite widely discussed. In fact, I could argue that cities have been part of human history for millennia and that they have been at the fore-front of change ever since the Mesopotamians started them in the Middle-East. What’s different today is that the areas surrounding these clusters of cities are changing in a way in which we have not seen them change before. Wherever change is happening, scientists are at the forefront of it.

Architect Rem Koolhaas says he sees future in the countryside. In a column for The Economist’s ‘The World in 2018’ series, he gives an example of his holiday in the Swiss mountains, where he had met a supposed farmer and found that he was a disgruntled nuclear scientist who had decided to flee the city and live in the countryside. Many such urban dwellers have started inhabiting this Swiss village on the weekends, bringing along urban design, Asian nannies and assistants.

We can generally see gentrification and its complementary rising rents in the countryside surrounding exactly these clusters of big cities. What we are talking about now is therefore less about individual cities and more about mega-clusters.

The idea is that we’re not just clustering in cities, but in regions of cities. Richard Florida put forward three mega-regions with the most economic output. These are Greater Tokyo with an annual product of $2.5 trillion, the Boston-Washington corridor on the US East coast at $2.2 trillion and the Amsterdam-Brussels-Antwerp region at $1.5 trillion. Compare this to the GDP of France, which is $2.47 trillion, let alone that of a smaller developed country like Switzerland, which is $660 billion according to the World Bank.

One effect of such clustering is the gentrification of countryside in these regions. But what does this mean for food production? Increasingly mechanised and organised in geometric efficiency, agricultural production for these regions, both within and outside of the places where the products are actually consumed, is undergoing rapid modernisation.

One such example is the Great American Harvest, a campaign of mechanised and sometimes robotised harvesters moving north to south across the United States, fed by information from satellites. Other examples are the proliferation of Chinese railways in the heart of Africa or the giant greenhouses and Tesla’s new mega-factory in Nevada.

All this sounds quite familiar to the world of ‘Hunger Games’, a fictional world where districts, each with a different economy, surround the capital district in which a totalitarian government resides. I would not go as far as saying that we live in totalitarian cities, but it is clear that mega-regions with their back-houses are starting to become a new world-order.

The millennials – a connected but polarised generation

As our social technology advances, our geographic boundaries tend to be losing significance for millennials. At the same time, increased connection with kindred spirits increases the tendency for bias. Is the concept of a nation state crumbling? Is religion being replaced by technology? How does the interconnected millennial generation view international development? These are some questions that surround the new generation of scientists.

Have you thought that connections on Instagram and Snapchat are superficial and fake, that these platforms are places for internet trolls? Think again. The Artidote is a community with accounts on both of these social media platforms, where the city-dwelling people – the young ones especially – share their private struggles with depression and other vulnerable thoughts.

This online, global community hosted on social media had the power to save the life of a pregnant girl who had decided to commit suicide. This highlights the extent to which this generation is connected in ways that transcend traditional geography and support networks.

Knowledge hasn’t just become more accessible and connected, it has made people more aware of each other, too. Millennials in particular are a part of a community of people who may live a whole world away, both spatially and culturally, but who are connected through a shared interest.

More young people today will believe in the new iPhone than in a traditional religion. Nevertheless, we still pray as much as our elders, the only difference is that today we increasingly pick and choose the aspects of religions that we like the most. Meditation apps like Headspace and YouTube channels like The School of Life, filled with philosophical ideas about life and relationships, are some of the places that these new spirituals may have turned to.

Photo Credit: Headspace

A newfound freedom of picking social, cultural and even spiritual connections suggests that traditional values connected to nation states and traditional religions may be becoming less appealing. At the same time, our generation’s tendency to pick and choose our own values and stick to people who reinforce those increases the proliferation of bias.

The clustering force and its impact on the millennial generation – a segregating power

A generally educated, extremely connected and well-travelled cohort within the millennial generation appears to be forming in these economic mega-regions. These people and the young scientists among them are starting to have an increasing influence on the world. Usually unknowingly, they impose their biases on it. But how are they connected in society? What are their interests?

Young educated people – and in this generation there are a lot of educated people – have become less invested in the idea of the nation as an economic, social and cultural unit. Many choose to emigrate, even if they do not necessarily use the word ’emigrate’. The word stems from a time when borders presented significant barriers to people’s world views, whereas today, we say that we are simply working in France for a while, moving to New York or taking up an internship in Singapore.

Fed by programs like Europe’s Erasmus exchange program, which is open to university students, and the international networks that exist in our top universities, most educated people tend to be the ones most exposed to a worldly view. These people realise that policies of oil refineries in the Middle East affect infrastructure in the Permafrost regions of Siberia; we realise that plastic pollution generated from waste dumped into Asian Rivers affect fish on our own plates, and that international development takes on a different meaning when it directly affects our own interests.

When the concept of action and consequence no longer restricts itself to a nation’s borders, but is visible on a global scale, it is no longer as possible to solely subscribe to a national agenda. I suspect that many such millennials would agree with London’s mayor Sadiq Khan in the following claim related to the power of cities, which he had expressed in a column for The Economist:

If the 19th century was defined by empires, and the 20th by nation-states, the 21st century will be remembered for the rise of cities

So far, I have been talking about the global millennials, the ones living in the world’s largest cities and mega-regions. While they are becoming increasingly connected with peers from across the globe and while they do partake in projects and economic activities that both surpass national borders and any previous scale of economic profit, another class of regionally isolated, less wealthy and less educated people – a global underclass, one could say – is starting to form in the wake of these mega-regions. The growth of this class is paired with the increasing popularity of far-right and extremist national policies.

How does this influence what science is doing, and why?

I have, until now, argued that the new generation of scientists is clustering in economic and creative mega-regions and that it wields more influence over the development of places that they have no direct connection with. At the same time, this generation is prone to social and cultural segregation from the rest of the world and harbours more self-justified and strong opinions. If the duty of geoscientists is to practise science to benefit the planet and our society as a whole, what might be at risk?

Related Articles

HOLDING THE 2030 SDG AGENDA TOGETHER by Tamsyn Barton

![]() CLIMATE CHANGE: TOO LATE? by Claude Forthomme

CLIMATE CHANGE: TOO LATE? by Claude Forthomme

SHAPING THE FUTURE OF OUR CITIES by Irina Bokova

SHAPING THE FUTURE OF OUR CITIES by Irina Bokova

Underrepresented interests

Scientists cluster in zones, and will continue to increasingly do so as the millennial generation enters the frontlines. Consequently, they leave behind some of the funding and attention that scientists in other parts of the world deserve.

If we were to consider the climate, for example, we would find that scientists from different regions, with varying perspectives rooted in what’s important to their own countries, will have a different interest in the broader concept of our planet’s climate.

South Asian scientists, having experienced the worst floods of this decade, may be more interested in how the climate affects monsoon cycles, and thereby also flooding risks, while in the Caribbean the focus would be on making extreme weather events, like hurricanes, less frequent. However, most of the best-represented and well-funded scientists of today live in these economic and innovation clusters.

East African scientists may be interested in how the changing climate may affect droughts in their area. The issue here is that the global climate models are often found to not be specific enough to be of use on the ground, and that Africa’s expertise on regional ecosystems, rainfall and climate has not been built into models, as the work done in Africa is usually not done by Africans or African institutions.

Encouragingly, South African climate researcher Francois Engelbrecht recently got in the news for developing a climate model that improves projections and supports the vulnerable community in decision making.

Though encouraging, this news was overshadowed by a deep-seated bias that exists in the scientific community against researchers in the global south. Scientific infrastructure, including publication visibility and funding, is anything but a level playing field. We live in a world where the affiliation to an institution is also a reflexive judgment of a researcher’s quality, resulting in many such scientists not being discovered by potential collaborators or funders.

Policy-driven research, but whose policy?

I hear a lot of my colleagues say that science, in order to stay pure and independent, should not get involved with politics. But even so, science will continue to have its place in society, one way or another, especially when this science becomes more applied. Research is often driven by values and interests which reflect the societies in which these scientists live.

A new buzzword for many earth scientists and a new driver for research efforts is ‘sustainability’. This is usually particularly tied to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which lists seventeen goals that verbalise the aspirations of western governments.

One such SDG is ‘no poverty’, while another aims for ‘life on land’ and another for ‘sustainable cities and communities’. The aims and objectives of people I know in the sustainability sector, including myself, sound exclusively admirable and morally sound. We are trying to improve the world around us and the people living in it.

A more critical viewpoint on these goals is to consider that the most powerful countries in the United Nations stand to gain from sanctifying foreign intervention, as well as that its efficacy hinges on overcoming some of the biases in research that I have pointed out earlier.

The SDGs and sustainability are a hype most present among the young people in metropolitan centers. Knowing that what happens in London’s backyard, whether that be rural Africa or rural Romania, affects London’s dinner, climate and clothing, it is not surprising that we take more interest in securing the sustainability of economies abroad.

The overall majority of United Nations headquarters is in developed nations, more precisely in the economic mega-regions of Europe and the United States. Unsurprisingly, most of the people I know who are interested in sustainability are either world-traveling United Nations staff or European diplomats.

The local Filipino and Malaysian development officers are usually implementers, while those living in the world’s mega-regions are the ones setting the agenda. At the highest level, local development officers of developing countries can improve the efficiency of implementation of the goals that are set in Rome, Geneva or New York.

What most of us who are involved in development – a sector that is ever-growing – may not realize, is that we are shaping the world in a way that increases dominance of a cluster of our most significant cities, and that we are doing so based on biases present in these regions.

No longer do we allow people to live life dangerously or to farm inefficiently. The Disaster Risk Reduction agenda aims to mitigate risk, while the SDG 2 aims to optimize agricultural production. Both work to optimize the efficiency of growing economies, which makes sense in the perspective of a global economy.

But do we have the right to tell people how to live? Should we drive people to give up their modest material means in exchange for becoming more efficient producers for our economy? Should we force them to sacrifice some of their ancestral and cultural riches in its wake?

As we push for sustainability, who will win and who will lose? How do we distribute the world’s resources and who will bear the cost of natural disasters?

We should not confuse the sustainability agenda and the SDGs with a moral holy grail. First and foremost, it is an agenda that supports the growth and well-being of a more connected global economy.

Ethical concerns should therefore be considered separately from such policies. Merely supporting a research application on the merits of supporting the sustainability agenda or an SDG should not be enough.

Towards more critical thinking by scientists

Science and scientists have a duty to benefit society as a whole, and should consider and communicate the negative impacts that some applications of their science might have.

Geoscientists have a unique knowledge-base about the earth to draw from, and can come up with scenarios that may not have been considered by those in the policy arena. It is the scientists’ duty to communicate their science, including – or especially – when they can envisage that other people’s use of it might have negative consequences.

As a geoscientist, I see the world is ready for some some rather powerful geoscience applications. This is why, in the next article, I will discuss the potentially darker side of science applications, in particular those of geoscience applications.