Much has changed since 2001 when John Le Carré, author of the best selling The Constant Gardener, attacked the medical trials system in use at the time, but much has not, with those harmed by medical trial missteps going far beyond Africa.

“It cannot continue that we allow patent laws to exercise the right of life and death on these people. It’s genocide. It simply means you kill the poor. And so that was what the novel was really about, the use of Africans as guinea pigs…being theoretically willing to test medicines which neither they nor their countries would ever be able to buy.”

John Le Carré, in an interview on March 28, 2001

Inevitably some human trials will prove unproductive, and nonetheless, are necessary. Under normal circumstances, health economic evaluation methodology would provide benefit-cost and cost-effective analyses to inform possible clinical trial decisions, and that would include potential adverse effects to participants. The present COVID-19 pandemic is anything but normal, and while extraordinary measures are required, the moral obligation to those who participate in such trials must remain.

Simply put, there is the need to be concerned and care for the people who serve as test cases.

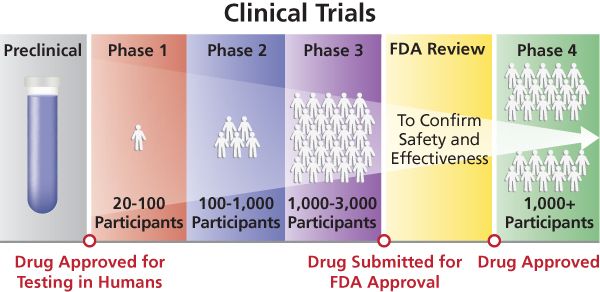

As COVID 19 continues to explode across regions and countries, the race for therapeutics and vaccines has intensified to the point that it is a preoccupation for everyone. To get pharmaceuticals to the needed level of safety and efficacy requires multiple trial phases for dozens of experimental versions, involving literally hundreds of thousands of participants.

According to the WHO, there are currently 220 vaccine candidates in development, with thirteen in clinical trials: five in China, three in the United States, two in the United Kingdom, and one each in Australia, Germany, and Russia. And according to the magazine “Nature” of the 2,000 COVID-19 trials registered around the world, 90% are in wealthy countries, with few in Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

That said, Africa’s first COVID-19 vaccine trial began on June 24 in South Africa. The trial started in Johannesburg, and some participants are residents of Soweto township.

Trudie Lang, the Nature author, put it this way: “in general, 90% of research helps less than 10% of the global population.” This time it is different: The global pandemic means its everyone’s problem, rich and poor.

Wherever trials are conducted, the ethical and moral issues remain. In an editorial on July 24, 2020, entitled A risk may be worth taking: Human challenge trials for a coronavirus vaccine should be considered, the Washington Post argues:

“Ultimately the wisdom of using human challenge trials to speed vaccine development will depend on a series of risk calculations… The risks of deploying challenge trials may well end up outweighing the benefits but with so much uncertainty…it makes sense to build the regulatory, medical and ethical infrastructure to support challenge trials now regardless of whether we feel confident we will use them.”

The logic of investment in the regulatory, medical, and ethical infrastructure is totally sensible but equally unrealistic, whether in the United States or in developing countries. History is replete with terrible medical trial outcomes, even in the last 25 years:

“In 2011, Pfizer a US pharmaceutical company set aside $35million to pay families of Nigerian children who had died or were severely harmed during a 1996 trial of a meningitis drug. The case raised serious questions about the design of the trial and the manner in which it had been ethically approved.”

David Pilling, July 23, 2020, in the Financial Times

Multiple examples of unethical trials by companies from Europe and elsewhere are identified in a paper by the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMOS) and the Wemos Foundation, both of the Netherlands.

We have had enough experience in this century with epidemics and pandemics to “theoretically” have learned how to conduct trials from HIV/AIDS, SARs, Zika, and Ebola pandemics.

WHO, the health community and politicians are aware there are core concepts to be followed, namely informed consent of participants, an oversight body that has regulatory teeth to ensure that rules are followed and that the outcomes are reliable. According to companies like Precision for Medicine, most reputable clinical trials are based on a randomized system, which is sound for assessing medical aspects but not particularly good at answering some key social and economic questions which bear on the relevance of the participant sample.

As in many country cases, participants volunteer guided by a sense of common cause. Others, in both developed and developing countries, decide to participate in a trial without fully understanding what they are getting into, attracted by monetary or other incentives. This often happens without due consideration given by those carrying out the tests to the medical histories of the participants or offering health care or other means should the participants fall ill.

There have been efforts to formulate, implement, and codify proper medical trials that take into account those who are to be tested. Beginning in 1964, the World Medical Association (WMA) adopted the Declaration of Helsinki, a nonbinding legal instrument under international law, which is a statement of ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, including research on identifiable human material and data.

The Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), an international nongovernmental organization founded in 1949 under the auspices of WHO and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural and Organization (UNESCO) has worked on ethics in relation to biomedical research since the late 1970s and has played a crucial role in developing guidance.

The current Helsinki Declaration version contains a set of 15 principles, including:

- Medical research is subject to ethical standards that promote and ensure respect for all human subjects and protect their health and rights.

- While the primary purpose of medical research is to generate new knowledge, this goal can never take precedence over the rights and interests of individual research subjects.

- Physicians must consider the ethical, legal, and regulatory norms and standards for research involving human subjects in their own countries as well as applicable international norms and standards. No national or international ethical, legal, or regulatory requirement should reduce or eliminate any of the protections for research subjects set forth in this Declaration.

- Appropriate compensation and treatment for subjects who are harmed as a result of participating in research must be ensured.

The Declaration has not been fully embraced by any significant player or authority in the U.S. Europe, China, Asia, Latin America, Africa, or elsewhere.

For example, neither the U.S. Food and Drug Administration nor the National Institutes of Health in training in human subject research, refer to the Helsinki Declaration. The 2016 U.S.21st Century Cures Act authorizes the Secretary of Health and Human Services to change rules applying to vulnerable populations to “ reduce regulatory duplication and unnecessary delays” and “modernize such provisions in the context of multisite and cooperative research projects.” And regulation waivers, including informed consent, are possible in “special circumstances [that] may include life-threatening medical emergencies, public health emergencies…”

The European Union Clinical Trials Directive published in 2001 only refers to the 2000 Helsinki Declaration version. More recently, the European Medicines Agency in April 2020 provided explicit guidance on COVID-19 Clinical Trials Management, namely:

“…pragmatic and harmonised actions are required to ensure the necessary flexibility and procedural simplifications needed to maintain the integrity of the trials, to ensure the rights, safety and wellbeing of trial participants and the safety of clinical trial staff during this global public health crisis. The points mentioned below are intended to provide guidance and clarity for all parties involved in clinical trials during this time. It should be noted that the simplification measures proposed in this document will only last during the current public health crisis until the revocation of this Guidance, when there is a consensus that the period of the COVID-19 outbreak in the EU/EEA, has passed”

A 2004 WHO Bulletin paper entitled “Beyond Informed Consent” by Zulfiqar A. Butta provides comparisons of global guidelines. Suffice to say, there are wide variations and differences between the WMA Declaration and those adopted.

A recent JAMA article (July 6, 2020) addressing the current pandemic stated:

“Mindful of prior vaccine safety challenges, regulators are appropriately cautious about approving vaccines for widespread use. Even during a pandemic, when much of the population is at risk, vaccines, unlike therapeutics, are administered to very large numbers of healthy individuals, and so must be extremely safe.

Phase 3 pivotal vaccine safety and effectiveness trials in the US typically enroll at a minimum several thousand vaccinated individuals and control study participants and should detect a major safety signal of an order of magnitude likely to outweigh the benefits of an effective vaccine. The FDA should explain how the agency will require and carefully analyze these trials for safety signals before permitting broader use of a COVID-19 vaccine.”

While in many cases the rules address “informed consent”, this is not the same as “understood consent”. Whether there is a lack of detailed explanation, difficulty in literacy or language, ethnic or cultural pressure by community leaders, or otherwise, an individual who agrees to participate may well have a limited idea of what this acceptance means in terms of health risks.

All aspects of a possible medical trial are–in theory– to be reviewed by an objective, independent committee, in some instances called an Institutional Review Board (IRB), Ethical Review Board (ERB), or Research Ethics Board (REB). The primary task of these bodies is to review the methods proposed for research to ensure that they are ethical. They are formally designated to approve (or reject), monitor, and review biomedical and behavioral research involving humans.

Sarah Babb, a professor at Boston College, has reviewed these sometimes controversial panels in Regulating Human Research, a book published by the Stanford University Press in January 2020. Here are some of her more salient points. Countries, she finds, have differing approaches: The U.K. has the government handle the entire process; the U.S. has the private sector do the review and submit it to the government for approval. Increasingly government-sponsored studies are using for-profit IRBs. This is because they are relatively more efficient and particularly good at reviewing multisite research. Even where undertaken by for-profits, the ultimate reviewers are government administrators who have substantial bureaucratic hurdles to deal with, handle massive documentation and take time to complete and approve a submission.

However, in a significant number of countries, there is no (or no effective) regulatory body. A 2007 paper entitled “The Structure and Function of Research Ethics Committees in Africa: A Case Study” published by PLOS medicine states:

“The WHO African Regional Office found that 36% of member countries had no REC (Research Ethics Committee). In the countries that did have RECs, most RECs met monthly, five met quarterly, and one never met. Finally, Milford [one of the authors of the case study] examined African RECs’ resource needs in the context of HIV vaccine trial preparedness, finding that 97% believed African RECs had inadequate training in ethics and HIV vaccine trials and 80% believed African RECs had inadequate training in health research ethics.

While there have probably been additions in the number and perhaps the quality of Sub-Saharan Africa RECs, it is clear that the situation has not advanced anywhere close to what is needed.

In sum, human trials are of high importance, and in the case of COVID-19 medical trials, they are urgently needed as the benefits from human pharmaceutical trials highly outweigh the risks. Nonetheless, there is a need for practitioners and governments to give greater attention to those who become participants in high risk therapeutic and vaccine trials, particularly as they are meant to benefit us all.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. In the Cover Photo:: The Constant Gardener. Photo from the film directed by Fernando Meirelles 2005 – Cassava Reviews