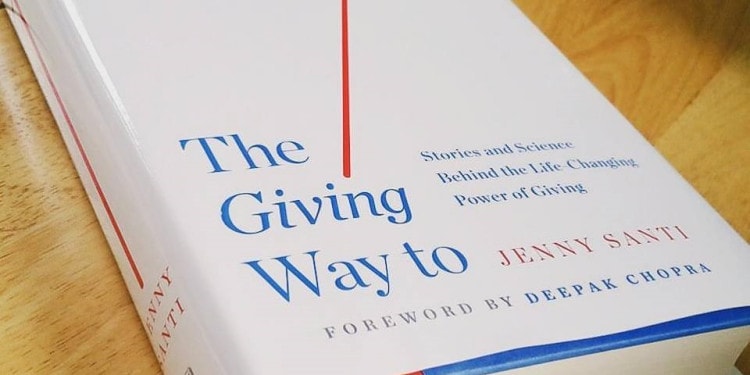

Jenny Santi, born and raised in the Philippines and now living in New York, has become something of a guru in the philanthropy community. When she was only twenty-eight, Santi headed for five years Philanthropy Services (Southeast Asia) for UBS, a Swiss global financial services company and the world’s largest wealth manager. Currently, a philanthropy adviser to some of the world’s most generous philanthropists, celebrity activists and foundations, she also shares her insights with the mainstream media, including recently with the New York Times, and has a new book out, “THE GIVING WAY TO HAPPINESS: Stories and Science Behind the Life-Changing Power of Giving” (Tarcher hardcover; published Oct 27, 2015) that is fast becoming a best seller on Amazon. She holds an MBA from INSEAD, went to the Wharton School as an exchange student, and attended New York University’s Heyman Center for Philanthropy and Fundraising, where she is a Chartered Adviser in Philanthropy.

In “THE GIVING WAY TO HAPPINESS,” Santi shares a growing body of scientific evidence that links giving with happiness, and helps the reader reflect on their own personal experiences in order to determine what and how to give. The book is filled with inspiring, personal stories of generosity that Santi has collected in interviews with, among others, Djimon Hounsou, Isabelle Allende, Goldie Hawn, Christy Turlington-Burns, Petra Nemcova, and Mo Ibrahim. For example, how supermodel Petra Nemcova overcame the tragedy she endured while vacationing in Thailand in December 2004 when her fiancé was swept away by the tsunami and never seen again while Petra broke her pelvis and was told she might never walk again; or how Joshua Williams who was only 5 years old when he started his foundation, turned into the “philanthro-prodigy” from Florida.

Impakter recently interviewed Jenny Santi and here are highlights of our conversation.

How did you come to the world of philanthropy, what were the events or people in your life that sparked your interest in charity work and giving?

Jenny Santi: Kids don’t really say, “I want to be a philanthropy advisor when I grow up.” It’s such an unusual job in a nascent field. My journey to what I do now was not a straight line but a series of dots that I have only recently been able to connect.

I was born in Manila, Philippines. Life there was comfortable; even as a middle class family, we had drivers, cooks and maids living with us at home. But even as a child, it bothered me that there was such a big gap between the rich and the underprivileged. I recall being chauffeured to school every morning, and without fail, every single day for 15 years that I was in school in the Philippines, a beggar would come knocking on the car windows and ask for loose change while I sat in air-conditioned comfort in the back of the car. I didn’t know it at that time, but I have often referred to that story whenever people ask me why I do what I do now. I was always idealistic and knew that I wanted to make a difference.

Perhaps the word “interest” in charity work is not the right one, passion might be more appropriate. Do you see yourself as passionate, and if so, how did it happen, did you go through an epiphany?

J.S.: A chance encounter with a “philanthropy adviser” while I was doing my MBA at INSEAD made me think that that’s what I wanted to do. I eventually got hired to be part of the philanthropy services team in a private bank. I fell in love with the work. Yes, I was passionate about the job, and passionate about the message I share in my book.

How did you grow into the role of adviser to philanthropic institutions?

J.S.: I threw myself completely into it, worked inconceivably long hours, and learned the ropes. I read every book on the field, attended courses around the world, such as those offered by NYU’s Heyman Center for Philanthropy. I also attended dozens of conferences to familiarize myself with the key players in the field. By age twenty-eight, I had become the Head of Philanthropy Services for Southeast Asia at the bank. Drawing from my business degree and my previous work experience as a management consultant, I gave counsel to some of the world’s leading private foundations and a category called “ultra-high net worth individuals”: people with investible assets of US$50 million and upwards, many of them billionaires on the Forbes list.

After many years working at the bank, it seemed time to move on to the next chapter, and so I started writing the book “The Giving Way to Happiness,” which draws on my observations and research on what giving does to the giver. I continue to work as a philanthropy adviser to wealthy individuals and public figures, over the last two years running my own practice, which I have set up in Singapore and in New York City.

Photo Credit: Twitter/Jenny Santi

What was your path to writing your book “The Giving Way to Happiness?”

J.S.: Having worked as a philanthropy adviser I was fortunate enough to have met a number of high-profile personalities. Soon after the idea of writing this book came to me, I asked three of them (in a carefully-worded, scrupulously polite and formal email which I hoped masked my quivering self-consciousness) if they would be willing to take a chance on me and express their views in a book that I intended to write about giving.

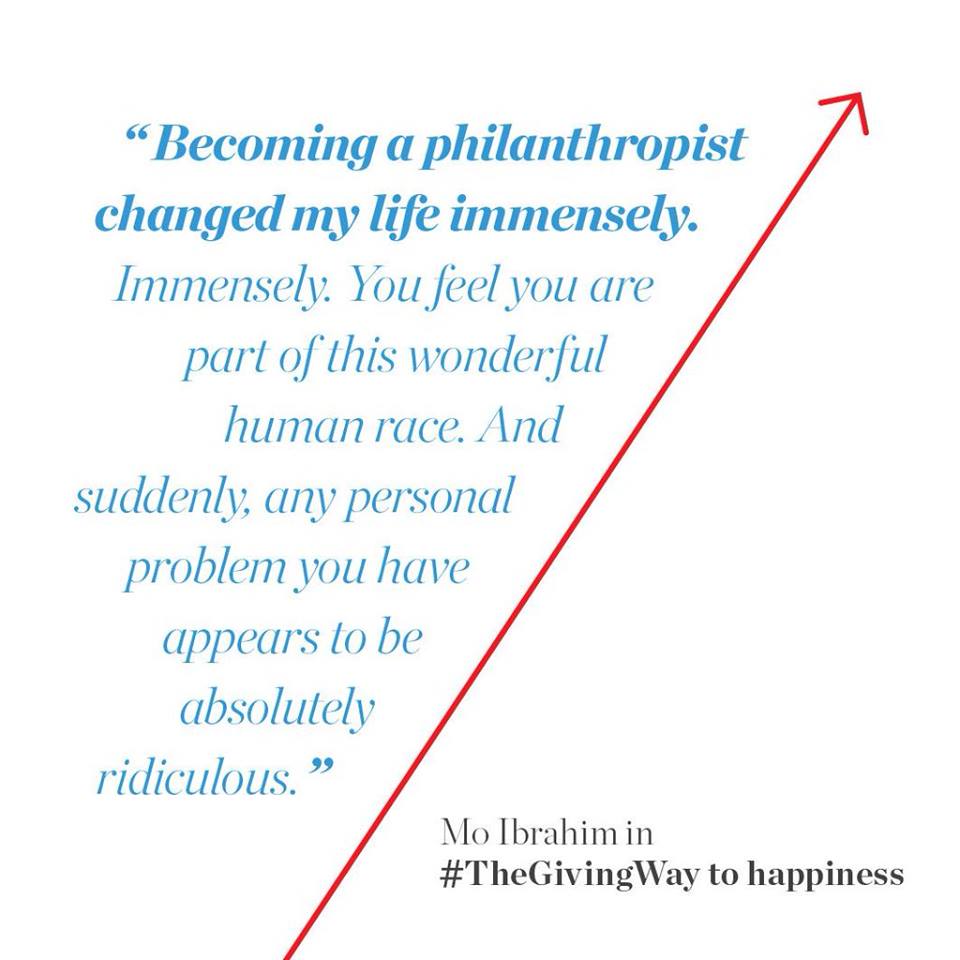

I started with communications entrepreneur Mo Ibrahim, because I find his fascinating personal story to be such a powerful example and because I knew my project would benefit from both his clout and his wisdom. David Foster also came immediately to mind because of his stellar reputation in the music industry and his street credit as a generally good human being. Rounding out my Top Three: Deepak Chopra. Because he’s Deepak Chopra. Need I say more?

I made a mental list of all the reasons they could possibly say no: Don’t want to appear smug and talk about how giving brought me joy! The questions you ask are very personal! How self-serving it is to say what my charitable work has done for me! But to my surprise, all three enthusiastically said yes.

Next, I approached a team of researchers at the University of British Columbia, and they were all too willing to share with me their latest studies on the links between giving and happiness. Day by day, my project was growing.

Although I started with my trusted contacts, I had to branch out further. I am no celebrity nor an ultra high net worth individual, and contacting these people was an exercise in resourcefulness. I dug out all the business cards I had collected over the years and created an Excel spreadsheet of all the people I would contact and how. One by one, I approached big-ticket donors and celebrities, always with a formal letter, asking them if they would like to join the ranks of the people who had already expressed a willingness to share their stories on the transformative power of giving upon the self. It was not my intention to write a book about celebrity giving, but I knew that if someone like Goldie Hawn was happy to share her story about finding joy in giving, it would be easier to get others to follow suit. Day by day, the “Confirmed” list in my spreadsheet grew, and although the life of a writer is solitary and isolating, I had a strong sense that I was surrounded by like-minded people believing in what I was doing.

Related Articles: “THE SECRET TO DRIVING CUSTOMER ENGAGEMENT”

“PRESERVING THE EXPERIENCE OF GLOBAL CITIZENS WITH MARIE CLAIRE LIM MOORE”

That’s fantastic! What happened next?

J.S.: Sometime around the fifth month, as if by magic, people started suggesting names of people I should be featuring in the book, instead of me making the request. In many cases, I was simply in the right place at the right time, as though the universe was conspiring to help me make this project happen. There were lots of days when I “just so happened” to be sitting beside exactly the person I needed.

To my surprise, even people who I’ve been told are obsessively private agreed to be interviewed. One of them was Ray Chambers (who has been called “the greatest philanthropist no one has ever heard of”), who prefers to work behind the scenes and is said to have paid people a lot of money to keep his name out of the press. I was touched when Ray said of this project:

What really appeals to me about your pursuit is how it could lead to the aggregation of hundreds of millions of people feeling that way, recognizing what giving can do for the self. And then, can we dare to hope, with the spreading of that knowledge, that we begin to see a shift.

I told him that was precisely what I hoped to achieve.

In the Photo: CNN Philippines interviews Jenny Santi. Photo Courtesy: Twitter/Jenny Santi

How did you manage this obviously demanding groundwork?

J.S.: Throughout this project there were many mountains to climb, red tape to cut through, my low budget to contend with, and thousands of hours flying back and forth between Singapore, New York, Geneva, Zurich, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington DC, Bangkok, London and the Philippines. So far I’ve logged 491,266 miles—and counting—on this project alone. I had to work around my interviewees schedules: the Oscars, the Cannes Film Festival, New York Fashion week, the World Economic Forum, or someone having to spend the day getting their star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame…

But looking back, I would not have it any other way! I felt, in the words of Paulo Coelho, that the universe was conspiring with me to get this project done. And I cannot adequately express my gratitude to all the people who’ve generously devoted time, energy and resources to this project.

Your book has a powerful message: that the act of giving can help you recover from a personal tragedy. How did you happen on this amazing insight?

J.S.: We know what giving does to change the world, but we have not heard much about what giving does to the giver. One of the things I observed not just in the process of writing this book, but in my career as a philanthropy adviser, is that so many remarkable individuals have demonstrated that as they face the greatest challenges in life—the death of a loved one, a troubled childhood, a debilitating illness, or collective grief —often the surest path to recovery is found in their devotion to something far greater than themselves. This book features the stories of bestselling author Isabel Allende, whose daughter died after slipping into a coma; the Alderman Family, who mourned with the nation as their son perished on 9-11; two-time Academy Award nominee Djimon Hounsou, who was once homeless and grew up in war-torn Africa; and Christy Turlington-Burns, whose father died of lung cancer and who herself suffered complications during childbirth.

We need to shift the way we think about philanthropy from a drudgery that we have to do out of necessity and moral obligation to something that we want to do because it brings us purpose, gives us a meaningful career, helps us recover from our own personal tragedies, brings us closer to our loved ones and friends, and gives us meaning beyond material success.

Photo Credit: Facebook/Jenny Santi

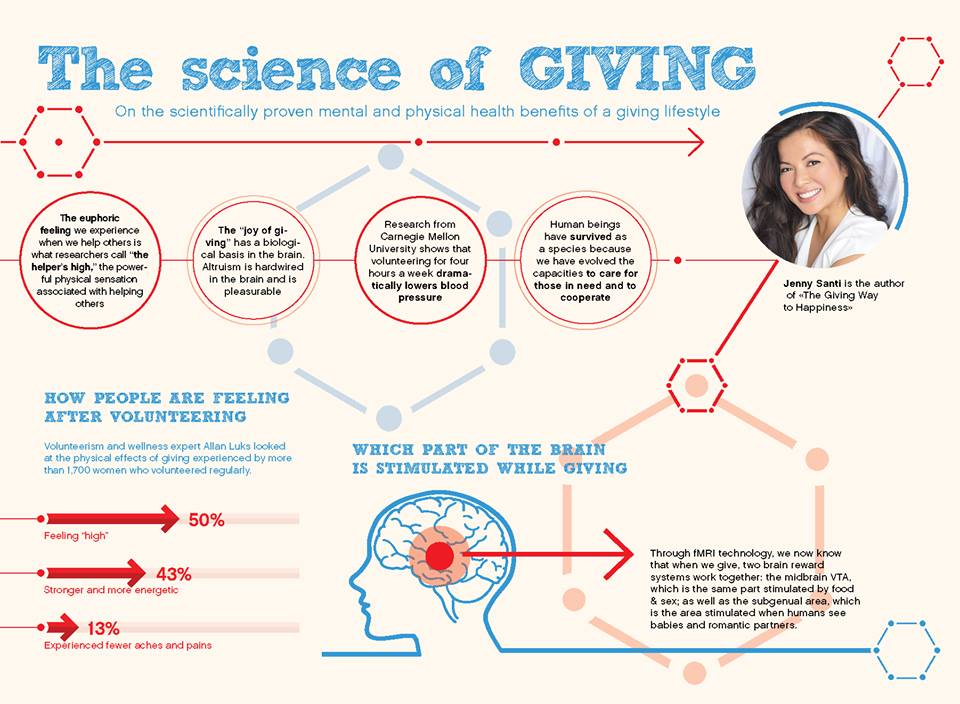

Your book is about the fundamental nexus between giving and happiness – and how to stay happy while giving. You have reminded your readers that science has recently come up with evidence that our brains are hard-wired for altruism. What do you say to the argument that our brains are also hard-wired for self-defense and egotism?

J.S.: Because of our very vulnerable offspring, the fundamental task for human survival is to take care of others. We have survived as a species because we have evolved the capacities to care for those in need and to cooperate. We see this even in the business world. One of the most popular business books in recent times, Adam Grant’s “Give & Take,” says that helping others drives success. Businesses now understand that in order to survive, they have to be a force for social good. In the 1980s, the movie Wall Street summed up the business community’s ethos as “Greed is good.” Three decades later, an alternative zeitgeist is emerging: “Giving is good.” I cover this more in “The Giving Way to Happiness.”

In your role as philanthropy adviser, what would you say are the main obstacles for efficient and effective aid delivery? How could we improve the “philanthropy industry” in order to weed out entities that are too focused on fund-raising and not enough on aid delivery?

J.S.: The key obstacle is that philanthropy is becoming a nuisance. Basically we need to shift the way we think about philanthropy from a drudgery that we have to do out of necessity and moral obligation to something that we want to do because it brings us purpose, gives us a meaningful career, helps us recover from our own personal tragedies, brings us closer to our loved ones and friends, and gives us meaning beyond material success.

Let’s face it. Whether consciously or subconsciously, we do good deeds to fulfill a need in ourselves. I have seen, through my work as a philanthropy adviser, that the motivation to make a difference is almost always very inwardly motivated: a mother starts a cancer foundation to recover from her daughter’s death; an abused wife starts a movement to end domestic violence to heal from her traumatic experiences; a billionaire sets up a foundation to fill the void he continues to feel, even though he has all the money in the world.

Looking at philanthropy from a historical perspective, would you say that there is now a sudden rise in interest? After all, as we just learned, Facebook’s founder, Mark Zuckerberg, has decided to give away his fortune at a much earlier point in his life (he is in his early thirties!) compared to other famous philanthropists like Warren Buffet. This is something of a paradigm change, do you agree?

J.S.: We have entered an era in which it is “cool” to give. Ten or twenty years ago, if you got out of a good school you’d work in Wall Street. Now, young people are interested in careers around social impact and social change. Nowadays there seems to be a general consensus that it is less cool to be a banker and way cooler to be a social innovator.

According to NetImpact, 72% of students, as opposed to 53% of workers, consider having “a job where I can make an impact” to be very important or essential to their happiness. Social entrepreneurship has exploded in the last ten years, and is now a track offered at more than 30 business schools.

Not everyone necessarily wants to work in the nonprofit sector, but everyone wants to have a career with a positive social impact. You don’t have to work in a nonprofit to make a difference.

nonprofit sector, but everyone wants to have a career with a positive social impact. You don’t have to work in a nonprofit to make a difference.

Is the phenomenon more marked in the United States or do you see it as going global?

J.S.: It’s happening globally. We have always been hardwired to do good, and in addition, there’s now greater awareness of social issues thanks to the media, particularly social media. Plus the rise of “celanthropists” (celebrity activists) who are able to leverage their fame to attract attention and support for the causes that matter to them – and consequently, their fans.

You are a sought-after adviser to philanthropy institutions and when the New York Times writes about philanthropy, it seeks your opinion; in a way one could argue you already have achieved your goal in life – do you plan to stay with it or do you have other goals?

J.S.: I don’t consider myself as having made it just yet. Right now I just hope the book has a long tail, and that many more people will discover the power of giving to change not only the world – but also the life of the giver.

A personal question, if I may. What do you do to relax, what does it take for you to recharge your batteries?

J.S.: I love animals, particularly dogs, so I spend time with them whenever I can. I also love being outdoors in nature, traveling to new places, and spending quality time with good friends.

_ _