There is no gender equality without access to reproductive health services, including abortion. In fact, economists are paying increasing attention to the economic benefits of investing in women’s reproductive health and finding gains not only for women but also for their families and for the economy at large. Women with access to a complete range of reproductive health services, including access to contraceptives and safe abortions, experience health benefits that improve their own lives and those of their children. They are also more likely to invest in higher education, participate in the labor market, earn more, and enjoy mobility across occupations. Children also experience health benefits – especially in developing countries – when their mothers have fewer children and more spacing between births and when their mothers are more economically empowered. There are also societal gains, including lower overall healthcare costs and overall economic growth. Yet a number of governments around the world, including the United States, are marginalizing and even restricting women’s access to contraception and safe abortion services. This piece shows why investing in women’s reproductive health is smart economics at home and abroad.

U.S. Policies around Contraception and Abortion

The most important legal benchmark in the United States regarding women’s reproductive health is the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, which held that prior to viability, a woman has a constitutional right to obtain an abortion. Almost twenty years later, the Supreme Court’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision reaffirmed women’s constitutional right to an abortion, but it also expanded states’ abilities to regulate women’s abortion access under the condition that the restrictions would not impose an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to obtain an abortion. The Supreme Court did not explicitly define “undue burden,” giving state governments latitude to try to reduce both the demand for and supply of abortion services.

This decision makes a shift in U.S. abortion politics toward the encroachment of restrictions on women’s access to abortions, and there has been an enormous expansion of state-level policies that restrict abortion access for women. These policies include parental permission requirements, restrictions on public funding, Targeted Regulation of Abortion Provider (TRAP) laws that place burdensome requirements on abortion facilities and doctors, informed consent laws, and mandated post-counseling waiting periods. The most common of the state-level restrictions are informed consent laws, which require that women receive a state-authored information packet about fetal development, risks of abortion, and alternatives to abortion. These packets often contain images of the fetus, a practice that is consistent with the strategy of anti-abortion movements to use fetal images and depict fetuses as people in order to persuade women to avoid ending the life of an innocent baby.

Such laws have a wide reach: two-thirds of all women seeking an abortion in the United States live in states with informed consent laws. Notably, research-based on evaluations by a panel of medical experts found that many of the state-authored information packets that are routinely handed out as part of the informed consent process have medically inaccurate statements.

State-level TRAP laws have also been encroaching on the ability of women to get an abortion, to the point that in 2016 the U.S. Supreme Court struck down TRAP laws in Texas which had forced doctors to have hospital admitting privileges and had mandated that abortion clinics meet requirements for surgical centers. These kinds of state-level restrictions are symptomatic of the strong pressures that anti-abortion groups have placed on U.S. lawmakers to restrict access to abortion at the national and international levels. Moreover, restrictions on access to abortion within the U.S. have disproportionately impacted low-income women and women of color.

Since January 2017, the Trump administration has enacted a set of policies at the national level that have restricted women’s access to reproductive health care, especially contraceptive access and abortion services. On the third day of office, Mr. Trump reinstated and expanded the Global Gag Rule. First implemented by President Reagan in 1984, the Global Gag Rule cuts U.S. foreign aid for family planning and reproductive health to foreign nongovernmental organizations that perform abortions or discuss the option of abortion with patients. Over the last 35 years, every Democratic president has rescinded the policy and every Republican president has reinstated it. Not only did Trump reinstate this restrictive policy, but he also expanded it to cover all global health funding. The policy puts $8.8 billion in global health funding at risk, up from about $600 million.

Under the expanded version of the rule, in addition to losing their family planning assistance, foreign NGOs that perform or promote abortions now lose U.S. funding for prenatal and postnatal care; prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS, malaria, Zika virus, and other diseases; screenings for cervical cancer and sexually transmitted diseases; immunizations; and nutrition services.

Additional restrictions on women’s reproductive health care by the Trump administration include defunding the United Nations Population Fund (the UN reproductive health and rights agency); appointing two conservative judges to the Supreme Court who are likely to support overturning Roe v. Wade; slashing funding for the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program; passing new Federal legislation that allows employers to deny insurance coverage of contraception for religious or moral reasons; and announcing the reinstatement of the domestic gag rule, a policy that bans recipients of Title X funding from promoting or making referrals for abortion services. Title X is the country’s federal program providing affordable contraceptive services, wellness exams, and screenings for cancer and sexually transmitted infections for both women and men. This policy restricting Title X funding has earned the derisive name of the Domestic Gag Rule since it similarly restricts the actions and words of healthcare providers in the U.S.

Policy Ineffectiveness and Costs

The restrictive policies are ineffective and costly. At the global level, detailed quantitative evidence in Rodgers (2018) for 51 countries across the developing world shows that the Global Gag Rule causes more rather than fewer abortions. To measure the rule’s impact, Rodgers analyzed Demographic and Health Survey data from 51 developing countries, covering about 6.3 million women per year. Using regression analysis (a rigorous statistical method), she calculated women’s likelihood to have an abortion before and during the most recent reinstatement period for which data are available (2001-08).

This policy – renamed by the Trump administration as “Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance” – does not achieve its objectives in the majority of countries that receive U.S. assistance. Rodgers also finds no conclusive or consistent evidence that a country’s own restrictive abortion laws actually reduce the number of abortions. If anything, restrictive laws are associated with more unsafe abortions in many developing countries. Women will find a way to have an abortion if they need to, even if it is illegal and in unsafe conditions.

In the face of an overall decline in abortion rates globally, the absolute number of abortions considered unsafe according to standards set by the World Health Organization has remained high. Between 2010 and 2014, about 25 million unsafe abortions took place globally each year. This figure appears to be on the rise since 2008 when approximately 21.6 million unsafe abortions took place globally. Moreover, data from the United Nations indicate that countries with highly restrictive abortion laws have substantially higher rates of fertility, teen pregnancy, unsafe abortion, and maternal mortality.

Domestically, abortion is at an all-time low, and teen pregnancy has also declined. A key factor explaining these trends is access to healthcare and contraception. Restricting this access is counter-productive. Moreover, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has supported mandated insurance coverage of birth control, saying access to birth control is “a medical necessity” for women.

Investing in sexual and reproductive healthcare services, providing effective contraception, and improving women’s access to family planning safe abortion is the key.

Economic Benefits of Access to Contraception and Safe Abortion

First and foremost, investing in women’s reproductive health is good for women. It also makes good economic sense for a number of reasons. First, access to comprehensive reproductive services improves women’s health. Women’s ability to control the timing and number of births is linked to higher maternal age at first birth, fewer children, and longer birth intervals. These factors are all linked to improved maternal health, which not only helps women but also has repercussions for healthcare costs and the overall macroeconomy. An important caveat to this point is that women not be coerced into choosing any particular method of birth control and that she has informed consent when participating in any programs related to family planning.

Second, women’s ability to control fertility is linked to increased educational attainment, higher labor force participation rates, and greater lifetime earnings for women. A recent NBER study covering more than 100 countries and 48 million women shows a strong inverse relationship between fertility and women’s labor force participation. Looking specifically at access to contraception, a famous study by Claudia Goldin and Larry Katz showed that diffusion of the birth control pill among young women led to a substantial increase in age at first marriage and their investment in professional and graduate schools. Greater educational attainment for women in term contributed to less occupational segregation by gender in higher wage professions. Martha Baily further showed a positive association between women’s access to birth control pill and their labor force participation rates, and she demonstrated that access to the birth control pill accounts for 30 percent of the increase in women’s relative earnings during the 1990s.

This point on the labor market effects of access to contraception also applies to the legalization of abortion. Abortion is an emotionally sensitive and politically divisive issue, yet a number of high profile economics studies have written about the economic ramifications of greater access to abortion. For example, Kalist (2004) found that by reducing unplanned pregnancies, legalization of abortion in the U.S. led to increased labor force participation rates for women. Bloom et al. (2009) took this point one step further and found that lower fertility arising from the legalization of abortion increases women’s labor supply and contributes positively and significantly to GDP growth. A recent study found that if anything, abortion law liberalization in the U.S. had an even stronger effect than the introduction of the birth control pill on women’s decisions to delay marriage and childbirth.

Not only do abortion regulations impact women’s labor supply, but they also affect occupational mobility. In the U.S., Targeted Restrictions on Abortion Providers (TRAP) laws that make it more difficult for women to seek an abortion are linked to increased ‘job lock,’ such that women living in states with TRAP laws are less likely to move between occupations and into higher-paying occupations. The authors also find that public funding for medically necessary abortions is associated with full-time occupational mobility for women.

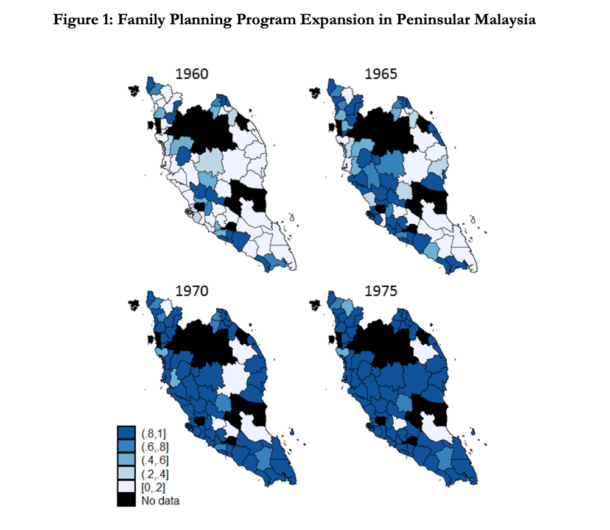

Third, investing in women’s reproductive health improves children’s human capital. In developing countries with high fertility rates, greater spacing between births and smaller family size both benefit children’s nutritional status, body mass index, development, and survival chances. In the United States with a total fertility rate of about two children per woman of reproductive age, a typical woman must use contraceptives for about three decades to achieve her desired family size. Smaller family size increases the resources available for each child, which contributes to improved child health and greater educational attainment. Some of these effects can result simply from contraceptive access, not necessarily contraceptive use. For example, evidence for Malaysia indicates that parents may invest more in their daughters’ education if they know that their daughters will have access to contraception later in life and can delay fertility. Closely related, in Sub-Saharan Africa, abortion law liberalization is linked to greater parental investment in girls’ schooling, with the rationale that access to abortion lowers the likelihood of a girl child dropping out of school in the event of an unplanned pregnancy.

These kinds of benefits for children can extend well into the future as women’s economic empowerment from lower fertility has indirect feedback effects for children. Numerous studies have documented strong positive links between child health and various measures of maternal health and economic empowerment of mothers, especially maternal education.

Investing in women’s reproductive health, including access to contraception and safe abortion, yields large benefits for women, children, and entire societies. When women can control their reproductive health, they have more control over their economic health and well-being. Research shows that it makes sense for US policy to support this agenda rather than marginalize women and their reproductive health with ideologically-based funding restrictions such as the Global and Domestic Gag Rules. Rather, integrating family planning and safe abortion into a full range of reproductive health and abortion services will go a long way to promoting health equity and improving women’s economic opportunities. It is time for policymakers to embrace the fact that women’s reproductive health rights are intricately linked with their economic empowerment and to the economy at large.

In the Featured Photo: An abortion rights activist holds up a sign in front of the Supreme Court as marchers take part in the 46th annual March for Life in Washington, U.S., January 18, 2019. Photo Credit: Reuters/Joshua Roberts

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.