When the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were being thrashed out at the United Nations, SDG 16 struggled to get an invite to the party. The Goal to promote peaceful and inclusive societies, provide access to justice for all and effective, accountable and inclusive institutions stood out to some countries as too interventionist, too sensitive, and too far outside the jurisdiction of the United Nations. Fortunately, a coalition of world nations successfully negotiated the Goal’s ultimate inclusion in the world’s “2030 development agenda,” reaffirming something intrinsically obvious to humans worldwide — that safety and justice underpin all other developmental pursuits.

In just a few short months, July 8-14 2019, member states assemble for a High Level Political Forum to review SDG16, along with others for example on climate change and on inequality — and then in September, all the goals will be reviewed at a special Summit. As we wait for the health check-up by the global doctors, to see our progress, everyone is looking nervous in the waiting room. While of course, the pace could pick up later, the current progress on Goal 16 is unlikely to be enough to meet the doctors’ expectations.

The UN Secretary General’s 2018 report on the SDGs is a catalogue of suffering and “untold horrors as a result of armed conflict or other forms of violence.” To take just one example: Every day, one human rights defender, journalist or trade unionist is killed while “working to inform the public and build a world free from fear and want.”

It’s obvious that all parts of society need to redouble our efforts to reduce violence and build peace given the strength of political headwinds blowing against all the ambitious solutions captured in the Goals. To do that, we must put our money where our mouth is: investing more in social movements and peacebuilders working to transform systems of violence and oppression worldwide.

The Pathfinders are a group of countries, international organisations, global partnerships, and networks, who have come together to drive progress on SDG16. To do this, they argue, we need to focus on action and on solutions, opening up space for what change looks like in the real world; to accelerate the pace of change — with all stakeholders; and to put the commitments at the heart of a broader mobilisation, energising partnerships to forge a new consensus about how to build more peaceful, just and inclusive societies. They have argued that we should take more of a public health approach to conflict, and have drawn heavily in their thinking from those Latin American mayors who drove forward concerted efforts to reduce homicides. At present, in their analysis, a lot is happening in SDG16+ but it is fragmented. Instead, we need to bring together different communities behind a drive to prevent all forms of violence. They point to the Millenium Development Goals aim to halve poverty and suggest that an objective to halve global violence should become central to the 2030 agenda.

It’s a bold challenge to all of us — including civil society. All too often, the international NGO community is very good at pointing the finger at other stakeholders. We can articulate precisely what “they” —governments and companies, usually — should do; we are less good at considering how we need to change. But in the past few years, a coalition of peacebuilding NGOs have come together precisely to work out how we should ourselves change. We’ve been re-evaluating our own missions, approaches and business models in the face of rising figures of conflict, death and polarisation. And we realised that as a sector we have underinvested in movement building and systems change, failing to scale our community-based models up to the policy, political levels and meaningfully address the root causes driving global levels of violence and division.

This may start to explain why we invest a fraction of a fraction in peacebuilding compared to aid or to security responses to conflict. For example, in 2016, the world invested 250 times more in the military than in peacebuilding.

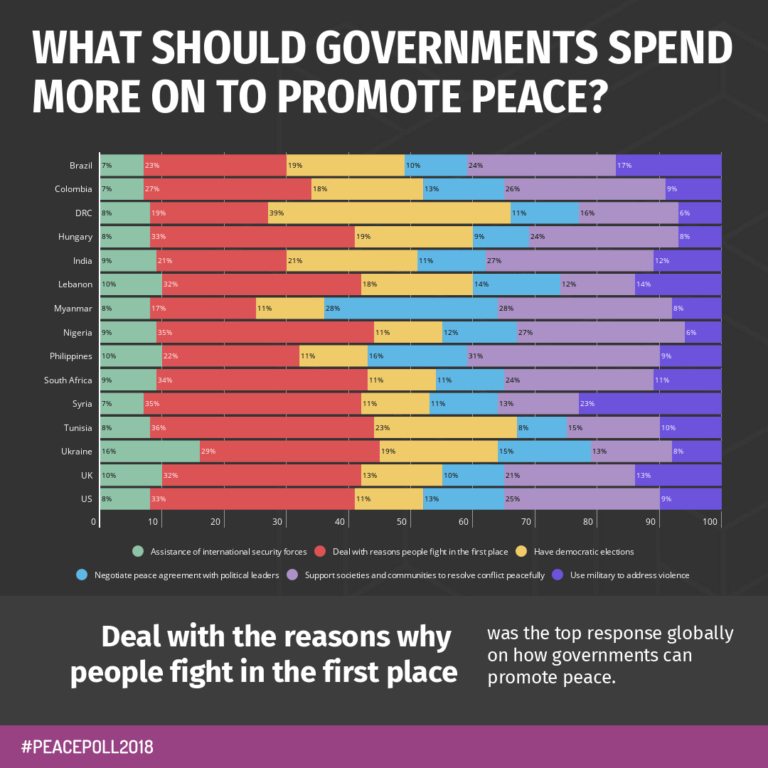

It may also be that politicians assume that military interventions command more popular support. But a new poll commissioned by International Alert with the British Council and undertaken by Canadian polling agency RIWI found that peacebuilding is in fact ahead in the popularity stakes. The polling provides useful input for policy-makers considering SDG16.

We polled over 100,000 people across 15 countries from the UK and USA to Nigeria and the Philippines. Given that the SDGs are global goals (in a welcome move away from the old North/South divide of the MDGs), this gives us useful information.

Asked why people in their communities were motivated to violence, “Lack of jobs or the need to provide for their families” topped the list (linking to the SDGs). This was followed by a sense of injustice and a need to improve one’s social status. Political and economic inclusion were regarded as fundamental to peace and security: 90 percent of respondents said economic inclusion was very or somewhat important to peace in their country; 83 percent said the same for political inclusion. DRC and South Africa perceived the highest levels of political exclusion, followed by the UK, Hungary and the US. Across the majority of countries polled, corruption in politics (which is a part of SDG16) was cited as the number one reason why people felt they had less political agency than five years ago. Eleven countries ranked it first, including South Africa, Ukraine and Nigeria.

Interestingly, the Pathfinders pull out governance as “the dog that is yet to bark, with too little focus on the institutional challenges in delivering 17 goals.”

When we asked people what was the most effective approach to creating long term peace, top of the polls was “dealing with the reasons why people fight in the first place,” followed by “supporting societies and communities to deal with conflict peacefully.” Prevention is clearly better than cure. These two elements constitute “peacebuilding” — a relatively underutilised tool compared to military intervention and humanitarian aid, both of which were ranked lower.

So the evidence is piling up that suggests: peacebuilding is effective and has an impact; it is cost-effective (see work by the Institute of Economics and Peace); and it is in fact popular with the public. In response, as NGOs we have concluded that we need to mobilise better and communicate better about peacebuilding. It is one part of our own strategies to get energy behind the goals encapsulated in SDG16.

We are still a fledging coalition, including all the world’s largest dedicated peacebuilding organisations from Search for Common Ground to the network GPPAC. We’ve undertaken our first action: to get peacebuilding in the dictionary. It is an indication of just how much mobilising is needed, that the very word peacebuilding had not been recognised — until now with three dictionaries already responding positively. We are still calling on other iconic names such as the Oxford English Dictionary to respond.

In a very different way, the Pathfinders have mobilised a group behind the justice element of SDG16, recognising that to meet the goals, we will need action far beyond the corridors of power in New York. The people of Mali have never heard of SDG16 — but they do know a lot about conflict and how to build peace — so let’s make sure that their ideas and voices are heard.

Just as the peacebuilding NGOs need to change, to raise our game and up the profile of our work, so too do the far bigger development agencies. The stakes are high. All the states that failed to achieve some or all of the MDGs were fragile or conflict-affected. So clearly we need to change our approaches and learn the lessons. Einstein’s famous definition of madness is continuing to do the same actions while expecting a different result. In the post-mortem the international community concluded that we need to work differently in such countries.

This was underlined by the UN and World Bank’s 2018 flagship publication, “Pathways for peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict.” In practice, it means looking at how activities from health to education can avoid exacerbating conflict (do-no-harm) and address underlying drivers of conflict (do-some-good) such as economic exclusion. This is a “conflict sensitive approach.”

On the policy side, progress has been made. Credit where credit’s due, the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), the Swedes and the Dutch have all put dealing with conflict high up their aid and foreign affairs policies. The reality though is that implementation is mixed and sound policies need to be rolled out with more pace and scale.

The 2015 OECD States of Fragility Report showed significant underspending in areas of ODA in fragile states that are critical to addressing the conflict. These areas are represented in the Peacebuilding and Statebuilding Goals (PSGs), such as: political reform, security and justice. On average, they represent 10 percent or less of ODA going to fragile states, according to both 2015 and 2018 States of Fragility Reports. The support that such states do receive has been described as “stopgap firefighting” that often leads to prolonged crises rather than sustainable development. So aid departments need to turbo-charge their commitments to working differently in conflict.

Making progress on the SDGs also means embracing greater universalism and adapting to the realities of fragility worldwide. For so long, development wallahs have argued that we must focus on the poorest countries. Morally, for aid, that was clearly a good course-correction away from using aid to benefit the donor. But conflict, and progress on SDG16, challenges that thinking. Syria, once a middle-income country, according to UNHCR, now has 70 percent of its population living below the official poverty line. Indeed, the majority of fragile contexts are Middle Income (six upper middle income and 24 lower middle income against 28 Low Income countries). States like Venezuela or the Philippines all have persistent conflict-dynamics and growing inequality which could radically reverse development trajectories. Middle Income status (a World Bank formula to determine eligibility for concessional grants and loans) is not a stamp of stability. A large-scale conflict in Nigeria for example would, as the most populous country in Africa, put many of the SDGs all but out of reach for millions.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“Women and Peacebuilding: The Key to Achieving SDG 5 in Afghanistan”

“Peacebuilding: Is It Cost Effective?”

SDG16 came about because the international community acknowledged that without peace, justice, and accountable governance, the other goals would falter. Indeed, that is the bedrock underpinning all the SDGs — you cannot make progress on one without the other, you cannot tackle poverty (SDG 1) for example unless you tackle conflict.

What is more the SDGs are meant to be universal and of concern to all government departments. In practice however, in many countries, the emails are still being forwarded to the development department. Instead, they need to examine just as much their foreign relations activities — which may indeed be undermining their aid, as in the classic case of Britain pushing for peace in Yemen while selling arms to Saudi Arabia. To get to peace, to ensure no-one is left behind, we need to tackle power.

It is not just Governments. NGOs will also need to change their game to avoid bad scores in the health-check. Some multi-mandate organisations such as Mercy Corps or Christian Aid are alert to the need to work differently. The majority of development NGOs have not yet grasped the need to work differently in conflict countries if they truly want to “leave no one behind” as the mantra goes. There is a need to focus on conflict, rather than just how to get around it — a recipe for unsustainable actions. For many institutions their approach remains unchanged from that under the Millennium Development Goals — a focus on the most vulnerable. The sad reality though is that alone, that will not work in conflict contexts where different dynamics keep people poor. The NGO community needs to change strategies and tactics, if we are to “leave no one behind” and do better on SDG16.

And companies will be under the microscope too, recognised as key partners for the SDG implementation. Research by KPMG found that companies often focus on goals that appear the easiest to achieve, such as Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG8), and overlook the more complex goals such as SDG16.

So if we are to make progress on SDG16 and therefore on many of the other, connected goals, we have to get on course and give more attention to tackling the big, hairy beast in the doctors’ waiting room: conflict. Five steps we can take:

- Adopt the Pathfinders’ SDG16+ framework for understanding the interconnection between the goals.

- Ensure that all aid in conflict-affected states applies a “conflict sensitive approach,” maximising the potential for peace across, education, health, infrastructure and governance initiatives.

- Build up the capacity of Governments, NGOs and companies to integrate conflict analysis into their designs, build up their capacity.

- Monitor peace impact and incentivise governments to report on peacebuilding. Alongside this year’s High Level Review, why not have an annual report for each country on its impact on conflict and peace in the world? It would be a salutary marker of what needs doing where.

- Mobilise for peacebuilding, highlight our successes, and join International Alert and others in building a more politically formidable transnational peacebuilding movement.