Accelerating human and animal vaccine development against the myriad of zoonotic diseases has been a prime strategy contained within the modern One Medicine-One Health movement. There is a vast and varied array of infectious animal diseases that can spread to humans. They are caused and sourced worldwide from viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites.

Well known, high profile examples include rabies, avian influenza (bird flu), and Ebola from virus origins. Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium, and an innovative preventative oral vaccine is already available to immunize its primary reservoir, the white-footed mouse, thereby reducing the pathogen’s presence in the environment.

Nipah virus disease is a frightening yet little-known viral disease outside its common regional occurrences, i.e., South and Southeast Asia, including Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore. Thus, most of the world has not experienced or been made aware of it. Bats or pigs that consume contaminated date palm sap can become infected, posing a risk to humans coming in contact with them. There are no available approved human vaccines or specific treatments currently available; there are no antiviral medications.

Public health and scientific authorities consider Nipah a significant threat today due to its very high mortality rate of 40 to 75% and its pandemic potential. Vaccine and treatment development are considered a high priority for this pathogen by the World Health Organization (WHO). Fortunately, to date, human-to-human transmission has not been efficient, and outbreaks have been reasonably contained.

A mutation or transformation of the virus could change this into a real-life horror movie scenario.

Without an approved Nipah vaccine or an effective therapeutic treatment, a pandemic disaster similar to but much worse than COVID-19 could result. Maintaining customary levels of homeostasis in humans would be in severe jeopardy.

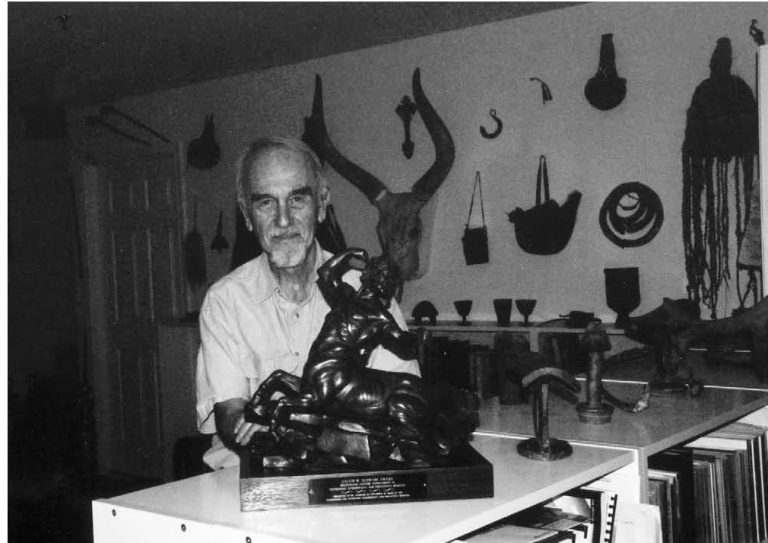

Mutations in humans are of major concern since there is a high mutation rate for RNA viruses like Nipah. The good news was a July 2025 announcement of a new vaccine being set for human trials in Bangladesh, a Nipah outbreak hotspot. A vaccine for Nipah was favorably reported in 2022 by renowned virologist/vaccinologist Thomas P. Monath, MD and his colleagues. Dr. Monath was a key participant in the development and testing of the new vaccine. Monath is a prominent One Health expert and activist and a co-founder of the One Health Initiative (OHI). He was the Sabin Vaccine Institute’s 2023 Gold Medal Awardee.

Over a decade ago Monath proposed a visionary approach to curtailing zoonotic diseases to the scientific community viz. “Vaccines against diseases transmitted from animals to humans: A one health paradigm.”

Highlights

- “Three frameworks for development and use of vaccines for control of zoonoses are provided.

- Framework I vaccines target dead-end human and livestock hosts.

- Framework II vaccines target infections of domesticated animals as a means of preventing spread to humans.

- Framework III vaccines target wild animal reservoirs.

- Collaboration of animal and human health disciplines (One Health) may accelerate new approaches to disease control.”

About 60% of all human pathogens are zoonotic (diseases transmissible from animals to humans) and approximately 75% of recently emerging infectious diseases affecting humans are diseases of animal origin. If mankind loses some more or most of the ability to treat these diseases with efficacious antibiotics due to ever increasing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) — another issue being addressed by a One Health approach — we are in big trouble.

Our immune systems are usually not capable of fending off most of these diseases, resulting in high morbidity (illnesses) and a higher mortality (death rate) than currently expected in our worldwide societies. However, if vaccine research and development are fast-forwarded, some of these can be prevented, eliminating the need for antibiotics to some extent.

This pursuit is certainly doable with adequate recognition and funding. The One Health Initiative considers it essential. Nonetheless, the anti-science/anti-vax and health illiteracy issues portend significant roadblocks. Moreover, problematic is the apparent remaining well-meaning but unrelenting future three-year quagmire with the U.S. Trump administration’s unabated, blind, unconventional, regressive Health and Human Services Secretary’s (Robert F. Kennedy Jr.) policies that oppose sound scientific/medical public health research data and endeavors to destroy an efficacious decades-long established infrastructure.

Related Articles

Here is a list of articles selected by our Editorial Board that have gained significant interest from the public:

However, principles of utilizing the One Health approach, i.e., multidisciplinary/interdisciplinary collaborations between animal health and human health industries and regulators, can definitely help develop immunization products for such purposes. Monath’s article gave reasonable guidelines to make it happen sooner rather than later. Examples of such vaccines were listed, including West Nile, brucellosis, Escherichia coli, O157:H7, rabies, Rift Valley fever, Venezuelan equine encephalitis, Hendra virus, Mycobacterium bovis, and Lyme disease (previously addressed).

Another 2013 publication discussed the significant food safety potential of using a vaccine in cattle to protect against human foodborne illness caused by E. coli. Also to be considered optimistically are “Plant-based solutions for veterinary immunotherapeutics and prophylactics.”

In simple terms, an internationally known physician, virologist, vaccinologist and One Health pioneer’s ingenious idea is to develop vaccines that protect domestic animals and wildlife thereby establishing effective barriers against human infections. Developing animal vaccines is less expensive and is less strictly regulated than are those for humans. Despite all odds, hopefully, a common-sense One Health approach can ultimately emerge with positive, non-partisan political support.