Since early 2020, the world’s attention has been on the global coronavirus pandemic. The pandemic continues to put massive stress on existing health systems, exposing their fault lines. As nations think about how to make health systems more resilient to current and future threats, one threat must not be overlooked: climate change is also impacting human health and straining heavily burdened health services everywhere.

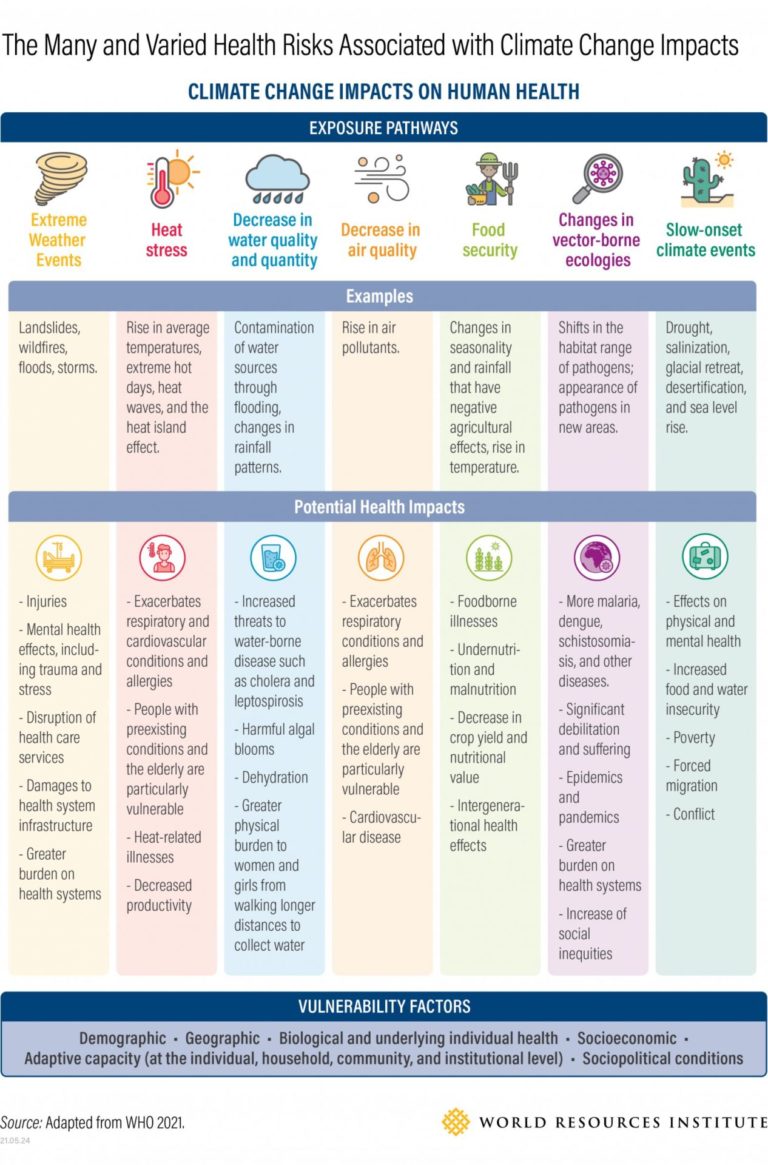

Health-related risks linked to climate change range widely, from increased likelihood of transmitting vector-borne diseases to decreased access to services as a result of natural disasters. For example, air pollution — the sources of which are often the same as those that drive climate change — kills 4.2 million people every year and makes countless more sick and debilitated. Ground-level ozone, a key component of air pollution, is even more harmful to human health when temperatures are higher. Climate change events like hurricanes and floods can also destroy or limit access to health infrastructure and services.

Human health is a priority in 59% of countries’ national climate adaptation commitments under the Paris Agreement and close to half of countries acknowledge the negative health effects of climate change. However, countries struggle to understand specific climate risks to health, as well as how to identify and fund comprehensive health adaptation actions. Only 0.5% of multilateral climate finance targets health projects. Domestic funding for this issue is also minimal or nonexistent.

This is unacceptable considering the need for resilient and stable health systems.

A new paper by WRI showcases how countries can integrate health-related risks from climate change into their national climate and health strategies and put them into action. Doing so is essential, not only in preventing the worst impacts of climate change, but in keeping people healthy and nations prosperous.

How Does Climate Change Affect Human Health?

There are many ways health risks link to climate change, which often intersect with one another. Common risks include:

1. Increased risk of vector- and water-borne diseases.

Climate change is redistributing and increasing the optimal habitats for mosquitoes and other pathogens that carry disease. In some cases, these pathogens are bringing infectious diseases into communities that had not encountered them before. For example, warmer temperatures expand mosquito breeding ranges, causing malaria to shift upslope into new villages.

One study projects that, because of climate change, up to an additional 51.3 million people will be at risk from exposure to malaria in Western Africa by 2050. These shifts can heighten suffering, increase countries’ burdens of disease and cause epidemics. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that one-sixth of illness and disability suffered globally is due to vector-borne diseases, which are predicted to spread due to climate change.

Climate effects related to changing rainfall patterns, water quality and water scarcity can also trigger or worsen diseases within a country. For example, Ghana is now facing a higher prevalence of cholera, diarrhea, malaria and meningitis because flooding contaminates and exacerbates sanitation problems and water quality. Cholera outbreaks in Ghana have a high fatality rate and are particularly frequent during the rainy seasons and in coastal regions.

2. Increased risks to lives and livelihoods.

Similarly, higher temperatures and extreme events — such as intense rainfall, stronger cyclones and increased risk of landslides — can cause physical injuries, water contamination, decreased labor productivity and mental stress such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorders. Hot weather and more intense heat waves reduce people’s ability to work and stay healthy; an environment that is too hot and humid makes it impossible for the human body to sweat and can lead to overheating and death.

Changes in the rainy seasons and other, slower-onset climate change risks like salt intrusion from rising sea levels can also negatively impact crop yields and food quality over time. This can lead to greater food insecurity and undernutrition. Bangladesh has the largest delta of any country in the world, and increasing salinity has already negatively affected its crop, fish and livestock production.

Even in places where agriculture yields may be boosted due to climate change, evidence has emerged that such increases can come at the expense of nutrition. These food security threats, in turn, affect people’s every day health, especially when it comes to child growth and development.

Environmental degradation and natural resources instability and competition exacerbated by climate impacts can also contribute to forced migration and social conflict. This can expose people to physical and mental health stressors, exacerbate existing health issues, lead to poorer living conditions and reduce access to affordable medical care.

3. Greater risk of social inequities.

The effects of climate change are especially felt by the most vulnerable, including people living in poverty, those who are marginalized or socially excluded, women, children, the elderly and those who are already ill or living with a disability. Without adequate support and funding, vulnerable groups will continue to suffer the most from the impacts of climate change on health.

The rising frequency, intensity and duration of extreme weather events will disproportionately impact the physical and economic capacities of people and households already struggling with weakened health and chronic disease. Due to their already debilitated or weakened immune systems, people with cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and other pre-existing health conditions are at higher risk of injury or sickness from natural disasters and other climate-related risks.

The elderly and people who perform heavy physical labor, including agricultural laborers, are especially at risk from the effects of increasing heat and heat wave events, which stress the heart (possibly leading to cardiac arrest) and can cause severe dehydration, which damages other vital organs like the kidneys.

When combined with poorer nutrition and water stress, the result is often worse existing health problems, which can further entrench generational poverty and systemic vulnerabilities. This, in turn, contributes to heightened mortality and morbidity at a wider scale, increasing countries’ disease burdens.

What Are the Challenges to Integrating Climate Adaptation into Health Plans?

Several technical and financial challenges remain when it comes to incorporating climate-sensitive risks into health systems. Many countries and groups lack a strong understanding of the links between climate change and health. This is made more complicated when considering that cause-and-effect is difficult, and at times impossible, to prove.

While environmental health and public health officers can see the connections, policymakers may not understand them without proper training. These knowledge gaps can lead to inconsistent policies and a lack of adaptation activities in health budgets.

Many countries also have inadequate finance to implement adaptation and health activities.

As our case study illustrates, in Ghana, for instance, policymakers have limited human resources and skills available to identify and develop appropriate adaptation measures to reduce climate-sensitive health risks. As a result, it is difficult to persuade Parliament to dedicate an adequate budget for such activities. Frequent changes in administration can also make it difficult to ensure consistent allocation of public resources for adaptation in the health sector.

Despite being a priority in national policies and international commitments, technical and financial support requests to the NDC Partnership and multilateral climate funds like the Green Climate Fund often vastly underrepresent health-specific activities.

In a global review of more than 100 countries, the UN found that only one in five countries is spending enough to implement climate-related health commitments. This gap will be further exacerbated by 2030, when the direct damage costs to health are expected to be between $2 billion to $4 billion per year — even without considering indirect effects.

How Can Governments Adapt to Protect Human Health from the Effects of Climate Change?

While it can be difficult to identify, understand and reduce climate-sensitive health risks, a lack of information should not prevent action or delay no-regrets adaptation measures to strengthen health care systems. No-regrets measures include actions that protect communities whether climate impacts materialize as severely as expected or not, such as building robust food and medical supply chains, retrofitting technology and equipment, increasing training of medical staff and establishing protections against interrupted health services.

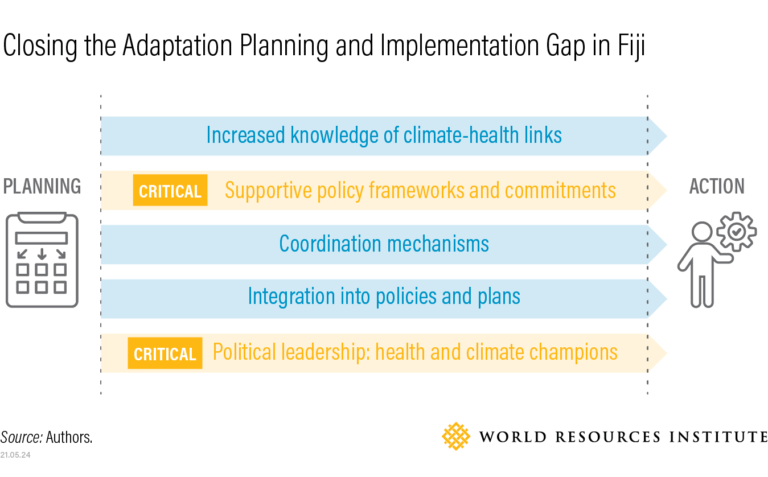

Governments can establish policy frameworks and collaboration mechanisms to provide needed guidance and support for no-regrets adaptation measures. Champions of climate and health issues inside and outside of the health sector can rally critical supporters and resources to influence policies and drive action.

Related Articles: Climate Change, the Environment, and Our Health | How Climate Change Contributes to Global Public Health Crises

Fiji, one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world, provides an excellent example of how to advance solutions. The nation developed and implemented its national Climate Change and Health Strategic Action Plan and integrated it into various policies and plans. The adaptation and health activities in Fiji’s plan are expected to increase the nation’s ability to provide and use reliable information on climate-sensitive health risks through an early warning system; improve capacity within health sector institutions to respond to these risks; and allow the nation to pilot disease prevention measures in higher-risk areas.

Fiji also set up a Climate Change and Health Unit within its Ministry of Health and allocated domestic funding to advance climate-health activities, like early warning systems, and build the capacity of health institutions to respond to climate threats. Health and climate change also remain on the political agenda thanks to the continuous efforts of and leadership from its Permanent Secretaries of the Ministry of Health, who encourage collaboration with other ministries.

Protecting the Health of Current and Future Generations

The links between climate change and health continue to grow in clarity and evidence. Policymakers can seize on the political momentum created by the global pandemic to strengthen their countries’ abilities to respond to a range of shocks and stressors — including the linked challenges of infectious disease and climate change. Strengthening the overall capacities and resources of health systems will increase adaptive capacity to deal with climate impacts, ensuring that current and future generations remain healthy.

— —

About the author: Stefanie Tye is a Research Associate in the Climate Resilience Practice (CRP) within WRI’s Governance Center. Stefanie co-develops technical guidance, information and tools to help national and subnational decision-makers plan for and implement climate adaptation and resilience.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: U.S. Army medical researchers take part in World Malaria Day 2010, Kisumu, Kenya, April 25, 2010. Featured Photo Credit: U.S. Army Southern European Task Force, Africa.