Derek Bok, Harvard University President, had a problem. The horrors of Apartheid were rocking the nation’s conscience, and demands for divestment from stocks linked to the South African regime were growing louder by the day. Bok needed a response.

In a 1984 letter to the Harvard community, he made his case. Dissenting from the students’ view that a mass withdrawal of economic and social capital could shake the status quo, he instead backed a policy of shareholder engagement. Harvard, he reasoned, should hold on to those investments, using its seat at the table to push for change from within while retaining the ability to profit in the meantime. As the battle lines were drawn, both he and the students knew that history would put the two theories to the test.

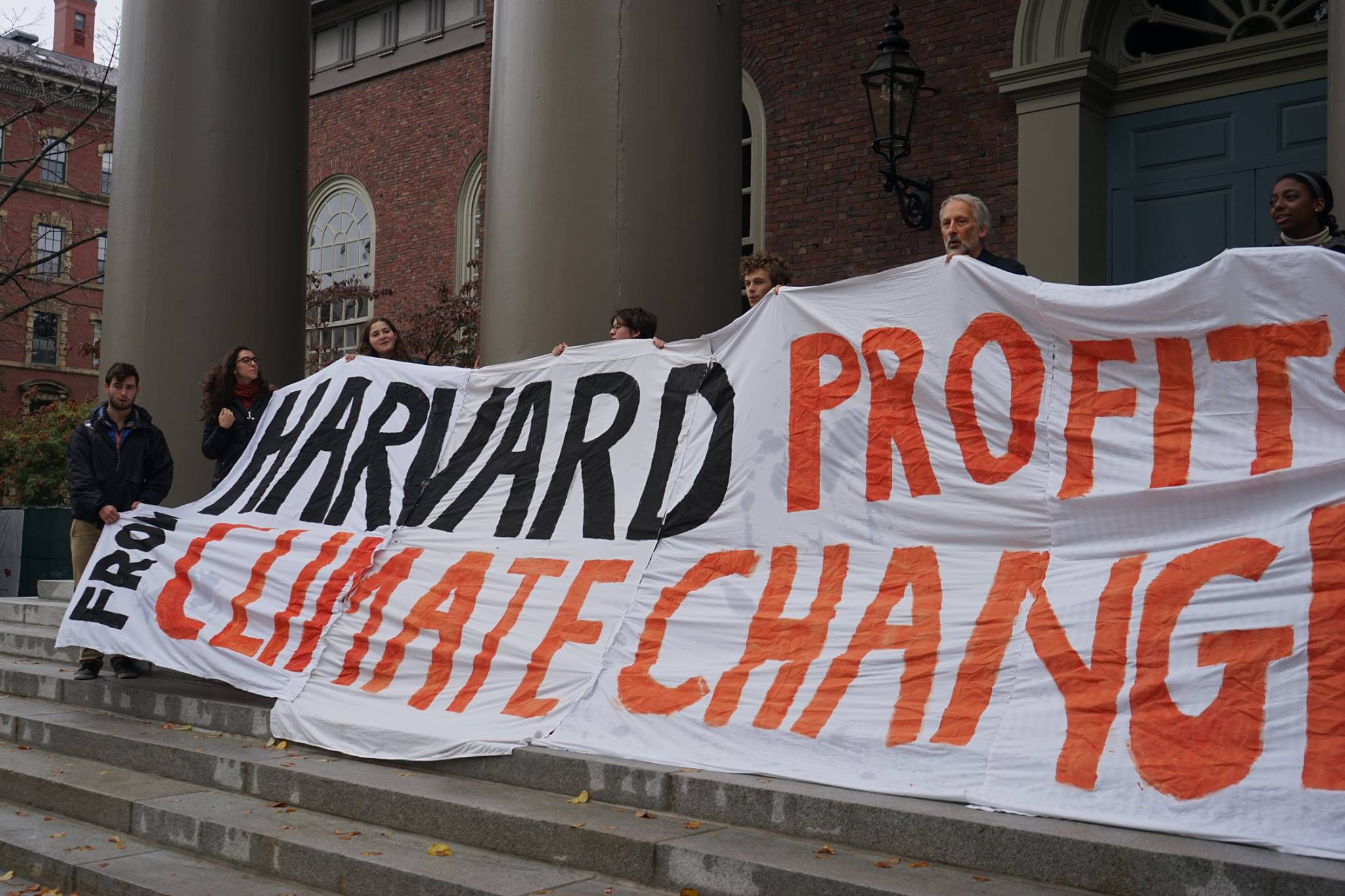

Decades later, the same dynamic is playing out as investors rethink their investments in the fossil fuel industry. In an age of impending climate breakdown, some believe, as Bok did, that shareholder engagement provides a win-win solution: Investors can engage with fossil fuel companies, pushing for climate action while maintaining their ability to profit from those holdings. But while it may be an appealing solution, when dealing with the fossil fuel industry specifically, it is one that ignores both the lessons of the past and the realities of the present.

The warnings from scientists, economists, frontline communities, and countless others could not be more stark: we are facing a climate emergency and must radically decrease our dependence on carbon-based fuels. Yet despite investor-advocates’ best efforts, ExxonMobil continues to plan its business around long-term fossil fuel dependency, BP makes climate pledges that fail to align with international climate agreements, Chevron continues to lobby against meaningful environmental policy, and so on. And it’s clear why engagement has failed to prevent these behaviors: The companies can’t afford to stop. Their profitability is contingent on the continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels, whatever the cost to our planet and our future.

The problem, in other words, isn’t a business practice, but a business model. There are many laudable success stories of shareholder engagement changing the former, such as in matters of workplace equity, labor practices, corporate governance, and more. But there’s little evidence to suggest that engagement alone can change the latter — it would be the difference between shareholders asking Coca-Cola to pay employees fairly, and shareholders asking Coca-Cola to stop making soda. So while investors may convince a company to put some solar panels on its corporate headquarters, convince a manufacturer to reduce the carbon emissions of its supply chain, or even convince an electric utility to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the mix of power it sends into the grid, it’s a much taller order to expect that they’ll be successful when asking oil and gas companies to abandon their core business model of selling fossil fuels.

Climate Action 100+, one of the largest environmental investor advocacy initiatives, provides a case in point. When the group last audited its own progress, it found that 0% of oil and gas companies it analyzed had clearly aligned their climate policy and lobbying positions with the goals of the Paris Agreement, while 100% maintained membership in trade groups lobbying against meaningful climate policy. Meanwhile, a majority of these companies are continuing with business-as-usual investments in oil and gas exploration: As of 2018, all fossil fuel majors had invested in projects that were incompatible with the Paris goals.

RELATED ARTICLES: Pymwymic: Pioneering the Change in Venture Capital |ImpactX: Addressing the Systemic Inequities in Business |How to use Socially Innovative Policy Making for an Inclusive Energy Transition |How To Make Investing In Green Finance Easier? |The “Green Chance” for Brazil |ESG Investing: No Longer Just For The Generous and Wealthy? |The Profitable Equation of Carbon Removal |

At best, shareholder engagement fails to prevent this corporate malfeasance. And at worst, it may provide cover for the industry’s intransigence, making it appear as if real change is happening even when it isn’t. Take Harvard, which announced in April that it had yet again rejected fossil fuel divestment in favor of engagement. It took no time for a major industry trade group to spin the decision as an endorsement of the fossil fuel industry’s vision for the future, co-opting the social power of the Harvard name to legitimize anti-climate efforts. Financially powerful institutions who embrace engagement risk walking into the same trap, as companies exploit investors’ hard-won credibility to justify continued inaction.

This is an industry that spends countless dollars every year harassing scientists and activists, fighting climate legislation, and misinforming the public, all with the goal of manufacturing a future that plays out on their preferred terms. When asset managers publicly tout fossil fuel companies as partners in change and praise each bit of nominal progress made through engagement, they may just end up making these extractors’ actions seem greener than they really are.

Thankfully, for investors who want to ensure that their investments end up on the right side of history, there’s another path. On its own, the moral urgency of stripping capital and social legitimacy from those working to slow climate progress provides reason enough for investors to cut ties. But increasingly, divestment is proving itself a prudent investment strategy, helping investors avoid the poor performance of the fossil fuel industry and hedge against a potential carbon bubble. In recent years, everyone from leading economists to managers of funds cumulatively worth trillions of dollars have joined the divestment movement, and it’s making a difference: As even industry players themselves will admit, the withdrawal of social and economic capital is posing real risks to their ability to access capital markets and thus fund the extraction of fossil fuels.

Two years after Bok wrote his letter, Harvard cut its ties with key Apartheid-linked assets, effectively acknowledging that a time of urgent moral crisis, divestment, rather than engagement, can sometimes provide the best hope of changing the status quo. History revealed that the students who had spent years fighting for that decision had been right all along: In the words of F.W. de Klerk, the final President of the Apartheid regime, “When the divestment movement began, I knew that apartheid had to end.”

Confronting the same questions all these decades later, we cannot afford to ignore these lessons. Shareholder engagement has, to be sure, proven itself a valuable tool in many instances. But so long as investors presume that it alone will nudge the companies most responsible for the climate crisis into good behavior, the chance to create a better future may slip between our fingers.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com