Are you intrigued by terms like Mutant Capitalism, Post-Capitalism, the Collaborative Commons, the Green Collar Economy and the Circular Economy? I was, and I did some research to clear up the definitions and gain an overview of the new economic paradigms in our current political discourse. We live in dangerous times, speeding away from the past and speeding to a fast-approaching but hard to define future.

In “Active Hope,” Ecophilosopher Joanna Macy, a student of deep ecology and systems theory, says that we are participating in a “Great Turning,” which she defines as “the essential adventure of our time. It involves the transition from a doomed economy of industrial growth to a life-sustaining society committed to the recovery of our world.” We need to define these waning and waxing economic paradigms if we are going to effectively participate in our future.

Free Trade: From Bootlegging to Market Fundamentalism

The latest (Merriam-Webster) dictionary definition of capitalism is a mouthful: “an economic system characterized by private or corporate ownership of capital goods, by investments that are determined by private decision, and by prices, production, and the distribution of goods that are determined mainly by competition in a free market.” The implication that the market is essentially private and should be as free as possible has more to do with recent ideas about market fundamentalism than capitalism as it was originally defined.

In Medieval times, “Free Trade” was a pejorative term for the illegal smuggling practiced by New Forest outlaws protecting their loot from duty and taxation. The Pilgrims were so displeased with the profit-taking capitalism of the joint stock company sponsoring their colony that they proposed a compact to mitigate its despotic demands.

The idea of a “free market” untouched by human hands would have dismayed Adam Smith himself. In 1776, when he published The Wealth of Nations, the well-being of the community trumped market freedom. He did not believe that a market left to its own devices would automatically foster the common good. Rather, he applied the civic principles of his earlier study of The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) to a socially regulated capitalism.

Our founding fathers were similarly suspicious of an untrammeled market in private hands. Thomas Jefferson was convinced that if corporations were left to their own devices they would undermine the public good: “We must crush in its birth the aristocracy of our moneyed corporations, which dare already to bid defiance to the laws of our country.”

In the nineteenth century, similarly, Lincoln was alarmed to “see in the near future a crisis approaching that unnerves me and causes me to tremble for the safety of my country…corporations have been enthroned and an era of corruption in high places will follow, and the money power of the country will endeavor to prolong its reign by working upon the prejudices of the people until all wealth is aggregated in a few hands….”

Can Capitalism be Saved?

Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt would have been heartily in favor of Occupy Wall Street’s protest against the private, corporate oligarchies presently undermining American society. In the words of Whole Foods’ CEO John Mackey, an anti-social conjunction of business and politics constitutes a dangerously “mutant capitalism,…a viable system gone deplorably amuck.” Mackey believes that humane business practices should replace the cut-throat capitalism fostered by market fundamentalists.

In “Saving Capitalism“ (2015) , Robert Reich also wants to reform its present-day excesses.

Photo Credit: Flickr/Democracy Chronicles

To Reich, as to Adam Smith, capitalism is not a supra-human force whose “invisible hand,” left to its own devices, will work for the good of the nation; rather, it is a human construct requiring human direction. There has been a concerted “consolidation of market and political power to overwhelm regulatory governance,” he asserts, to the extent that no matter how hard 99% of Americans work, their earnings are no longer commensurate with their merit. As a result, whole swathes of the working and middle classes have descended into poverty. Reich wants to save capitalism by imposing reforms upon the oligarchy that has usurped its democratic structure. He calls upon ordinary citizens to organize politically, retake Congressional seats, back legislation against corporate abuse, and redistribute income fairly.

Bernie Sanders and Democratic Socialism

In the 2016 Presidential Primary, Reich was an avid supporter of Bernie Sanders who espouses a socialism that gives government a stronger hand in the economy. Although Sanders talks about a radical economic revolution, he wants to democratize a dysfunctional economy rather than eradicate capitalism from it. Democratic Socialism has always been strongly anti-communist; Sanders’s reforms are more in line with European Social Democracy than with than with “government takeover” or the totalitarian state capitalism.

Related article: “HOW WATER SAVED ICELAND FROM AN ECONOMIC CRISIS“

In the interest of full disclosure, I joined the Democratic Socialist Party, founded by Norman Thomas and led by Michael Harrington, in the 1970s. Michael Harrington’s Socialism and Toward a Democratic Left influenced A. Philip Randolph’s A Freedom Budget for All Americans and Martin Luther King’s vision of economic civil rights in Where do we Go from Here. These four books were my original inspiration as a grassroots activist.

Can Our Economy Go Green?

In the 1990s, when I first spent time in Northern Michigan, environmentalists were in a pitched battle against furious local folk concerned about their employment and hostile to educated middle class elites telling them how to behave. Then the Michigan Land Use Institute (now called The Groundwork Center for Resilient Communities) set up shop to listen to what community members really wanted and mediate local solutions for their common good.

Fortunately for the future of our beloved planet, such either/or deadlocks between environmentalists and local people are giving way to a variety of collaborative paradigms. Van Jones , in “The Green Collar Economy: How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest Problems“ calls for environmentalists to replace their “David and Goliath” practice of small, elite groups taking on corporations with “Noah” methods involving the whole community:

“Instead of preparing to protest against a giant, as David did, perhaps it is better to prepare to lead a community through a crisis and into the future beyond that crisis, as Noah did.”

In this paradigm, multiple stakeholders seek mutually agreed upon goals rather than belligerently hurl themselves making “targets” of each other.

“The green movement must attract and include the majority of all people,” writes Van Jones, “not just the majority of affluent people.” Nor should the 99% pit itself against the 1%: with more “Eco-populism and less Eco-Elitism”, the full 100% should prosper. And that includes the victims of environmental injustice, rising out of a deeply embedded structural racism leaving the poor and people of color to suffer far more than the elite from the impact of climate change.

In a 2016 article Jones aligns himself with Robert Reich and the Democratic Socialists in seeking a “Green New Deal” which is “neither a big nanny government nor small government” but “a smart, supportive, reliable partner to the forces that are working for good in this country.” His vision of green capital, green technology, green investment and green entrepreneurs is profoundly democratic in its redistribution of the fruits of production, radically altering the mutant capitalist profit motive to a “triple-bottom line” paradigm balancing “profit, planet, and people.”

Post-Capitalism: Pipe Dream or Possibility?

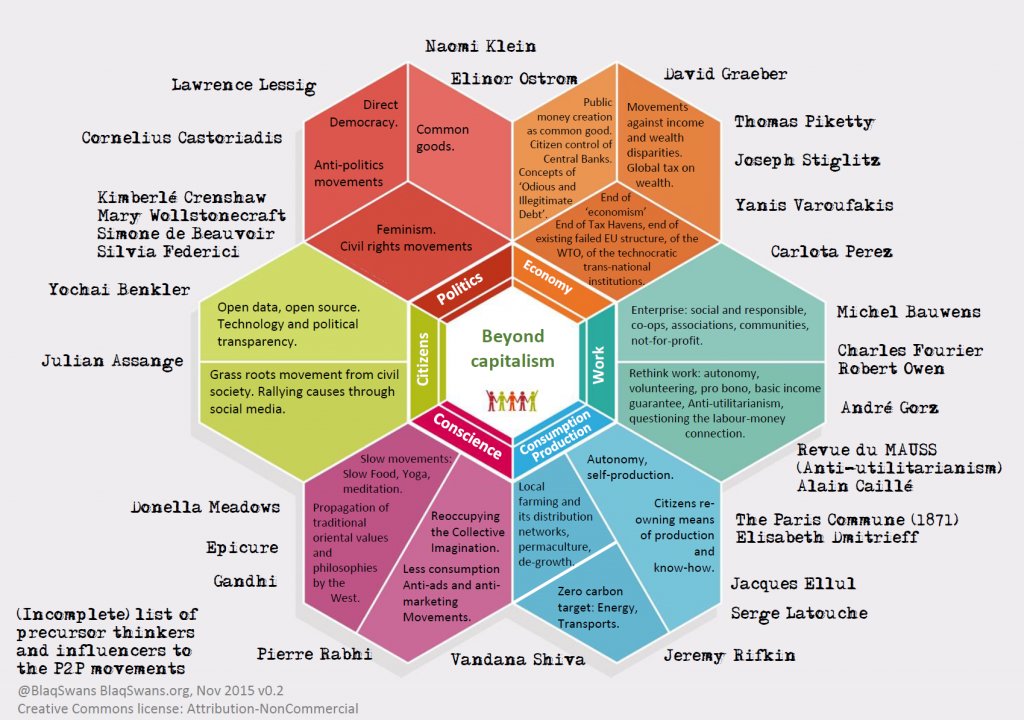

From the point of view of the BlaqSwans Collective, Peer2Peer, and the Commons Transition a collaborative commons is a viable alternative to capitalism.

The idea that such a “post-capitalist paradigm is a utopia thought up by isolated hippies” has been disproven by multiple instances of transition from “a central, hierarchically-controlled society to a horizontal, decentralized, and bottom-up working unit.” They agree with Van Jones in calling for the radical restructuring from a top-run to a grass roots economy: “We are already deep into a “change of era” from industrial capitalism to an “emerging post-capitalist paradigm, underpinned by peer-to-peer and collaborative dimensions.”

In a January 2016 article on “Mapping the Emerging Post-Capitalist Paradigm and its Main Thinkers,” they provide useful charts of “Current Capitalist Paradigms” and “Beyond Capitalism.”

Photo Credit: BlaqSwans

Among the “Precurser Thinkers and Influencers of Post Capitalism” is Naomi Klein, whose bestselling book “This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate” (published in 2014) rejects capitalism as a “zombie ideology” encouraging the fossil fuel industry to rake in huge amounts of money while trashing the planet. In a review of Klein’s book, “Can Climate Change Cure Optimism,” Elizabeth Kolbert notes that since climate change is the result of capitalism it cannot be mitigated by a capitalism based on perpetual growth and consumer consumption. Klein believes that the shock of climate change is sufficiently horrific to drive deep structural changes; We need to “curb capitalism” in order to “save the planet.”

According to Klein, our way of looking at the world has been influenced by the enlightenment paradigm that “the earth is not a living system, a mother to be feared and revered, but rather this inert thing…from which wealth could be extracted infinitely.” The impact of climate change forces us to discard this perspective, along with our “market-logic” belief “that our greatest power is as consumers.”

The more we consume, the more fossil fuel we burn and the more waste we dump, the greater the impact on our environment of carbon pouring into the atmosphere. The unusually high floods, intense and frequent storms, droughts, wildfires and extinctions we are experiencing are “telling us that we need an entirely new economic model and a new way of sharing this planet. Telling us that we need to evolve.”

In contrast to the savage “evolutionary” capitalism of “The Gilded Era” fostered by Herbert Spencer’s dog-eat-dog version of big companies swallowing up smaller companies for the good of the whole (Andrew Carnegie was an ardent adherent to his concept of industrial social evolution), today’s economic paradigms are evolutionary in a radically different sense deriving from our human capacity for altruistic adaption.

Like Van Jones and the Democratic Socialists, Naomi Klein calls for us to abandon the economic “meanness” inherent in capitalist concept of zero sum competition to “a worldview based on inter-connection,” replacing selfishness and greed with solidarity and compassion.

Can We Collaborate?

Jeremy Rifkin describes “The Rise of the Collaborative Commons,” as “a new economic paradigm” emerging as capitalism declines. “The Commons” is an historic land use policy by which certain pastures or arable fields are held for common rather than individual usage. The enclosure of commons traditionally grazed and farmed by ordinary people impoverished whole villages in England. The draining of the East-Anglian Fens (on which my eco-fiction novel series Infinite Games is based) is an example of early market capitalism destroying the habitat of a self-sustaining culture. It was begun in the 1630s by “Merchant Adventurers” similar to the shareholding companies sponsoring the Plimoth Plantation.

Joshua Rifkin sees a new social commons outstripping the market economy in The Zero Marginal Cost Society. Abetted by the Internet and a plethora of innovative technologies, the new commons is shifting from the paradigm of top down economic domination by corporations to “a deep social transformation” of grassroots sharing of local resources.

What do such solutions look like? “The Circular Economy” was first defined as “The Circular Model” proposed by the European Commission in 2014. I ran across the term in Liz Cunningham’s Ocean Country, a memoir/odyssey in which she travels the world’s oceans to find out how people are mitigating the impact of climate change. “These solutions were like a wheel that had finally begun to turn, “ she writes, “part of what was being called the ‘circular economy.’ It was based on the idea that the take-make-dispose model, which relied on large quantities of resources and energy, was increasingly unfit for the reality [of climate change] in which it operates.”

In the Photo: Cunningham with a fisherman’s collective on the island of Kaledupa in Sulawesi Photo Credit: Liz Cunningham

In the Tukanbesi island of Wangi-Wangi near Papua, New Guinea, Cunningham visits fishing communities whose stocks are decimated by overfishing, dynamite bombs and cyanide poisoning, combined with pollution from sewage run-off to damage marine life and kill off coral reefs. The fishermen created a forum to agree on common goals: “If someone uses the bomb or cyanide, we go to him and we talk. This is our reef, we say. If you do this, no one will have fish.”

And Cunningham notes:

“The fisherman have begun to pierce the armor of that goliath of problems, the Tragedy of the Commons: the tragic loss of common resources because of an inability to forego narrow self-interest and agree how to preserve them.”

In a world away from the worried Pacific islanders, among the urban, sophisticated culture of Parisian haute cuisine, Cunningham discovers a collaboration of chefs, fishmongers, middle men and fishermen determined to foster sustainable sandeel fisheries. “The natural feeling of a fishermen is that of a hunter, “one of them tells her. “Now it’s totally different, because we share the fish. We are no longer hunters.” To see fishermen replacing individual for community well being, she concludes, “Is like Columbus announcing that the world isn’t flat.”

The fishermen’s shift to a “round world” paradigm consists of scientific monitoring (which they pay for), and “adaptive, community-based, networked, task-specific” initiatives. Or, as one of the Parisian Chefs puts it, “The message is that we are able to put back something that seemed completely out of control. All we need is political will in order to go toward sustainability.”

Can We Do It? Political Strategies

Even while chronicling serious cutbacks to his hopes following the 2012 election cycle, Van Jones, in “Rebuild the Dream“ (2012) keeps his eye on the prize and provides roadmaps to get there:

“We must upgrade the industrial model itself, bringing forward the cleanest technologies and wisest practices, as fast as possible. To do that, we don’t need to go backward to communism. We need to advance toward a better capitalism. To solve our problems, we don’t need authoritarianism. We need a more robust democracy with less power for the polluters and more power for the people.”

We can get there by cultivating a “deep patriotism” that extends the basic American value of “liberty and justice for all” to “include people in the business community who want to create jobs in the United States, don’t dodge their taxes, invest in the country, and run corporations that respect our air and water.”

Bernie Sanders, Robert Reich, Naomi Klein, and Jeremy Rifkin would agree that success of their radically new economic paradigms is a matter of developing community and political will. The plethora of local actions and successes I read about while researching this article convinces me that there is a strong, varied and pragmatic grass roots movement already afoot.

Politically, the winds are changing. The Citizens’ Climate Lobby notes, for example, that in the last two years there has been a significant shift in Republican attitudes to climate change, manifest in a bipartisan Climate Caucus in the Republican controlled House of Representatives for which the only membership requirement is that you join with a member of the opposite party.

The Citizen’s Climate Lobby: Ground Shift in Congress

It seems to me that the proponents of “saving” capitalism by reforming it from within and those who believe that we must embrace “revolutionary” post-capitalist paradigms have enough in common to join forces on behalf of our beloved planet.

All we need is to rise above our over-intellectual, elitist tendency to insist upon the Theoretical Perfect to undertake a collaborative and inclusive quest for the Common Good.

When I am overwhelmed by the terrifying damage that climate change wreaks upon the earth and feel helplessly puny in opposing it, I take comfort in Joanna Macy’s application of “deep ecology,” to the psychology of active hope: “The term deep ecology, coined by Norwegian Ecophilosopher Arne Naess, captures the essence of this shift.”

It is “when we perceive our deep identity as an ecological self that includes not just us but also all life on Earth,” that we are able to take action with others. Learning about these new, green, circular and hopeful economic paradigms is the first step, but only if we take action will we feel the wind beneath our wings to lift us into that great turning, the essential adventure of our time.

Recommended reading: “‘TIDE HAS BEGUN TO TURN’ ON MIDDLE CLASS JOBS“