Could evolutionary genetics – the study of our genes over time – come to our aid in fighting future pandemics? We have been coping with widespread infectious diseases including HIV/AIDS, and a series of COVID pandemics – many of which have been tamed and cured. What is not known is how well we will cope with the next infectious disease threat and, as I recently argued, it’s time to get serious about preventing pandemics. The extent to which our twenty-first-century systems will be able to effectively respond is still unknown. But new groundbreaking scientific efforts have been looking back and forward to gauge and enhance our capacity to deal with whatever comes next.

This much we do know: our immune systems have evolved over time to respond to different pathogens – so much so that copies of genes that protected some fortunate humans in the mid-1300s against the Black Death, a deadly plague that killed millions, have been passed down over generations.

“When a pandemic of this nature – killing 30 to 50 percent of the population – occurs, there is bound to be selection for protective alleles in humans, which is to say people susceptible to the circulating pathogen will succumb,” explains the evolutionary scientist Hendrik Poiner in a paper on the subject. “Even a slight advantage means the difference between surviving or passing. Of course, those survivors who are of breeding age will pass on their genes.”

And these lucky survivors will of course more than likely have lucky offspring.

Or, as evolutionary biologist David Enard of the University of Arizona told NPR: “The evolution is faster and stronger than anything we’ve seen before in the human genome… It’s really a big deal. It shows what’s possible [for humans], in terms of adaptation in response to many different pathogens.”

Nor are these scientists alone in their findings.

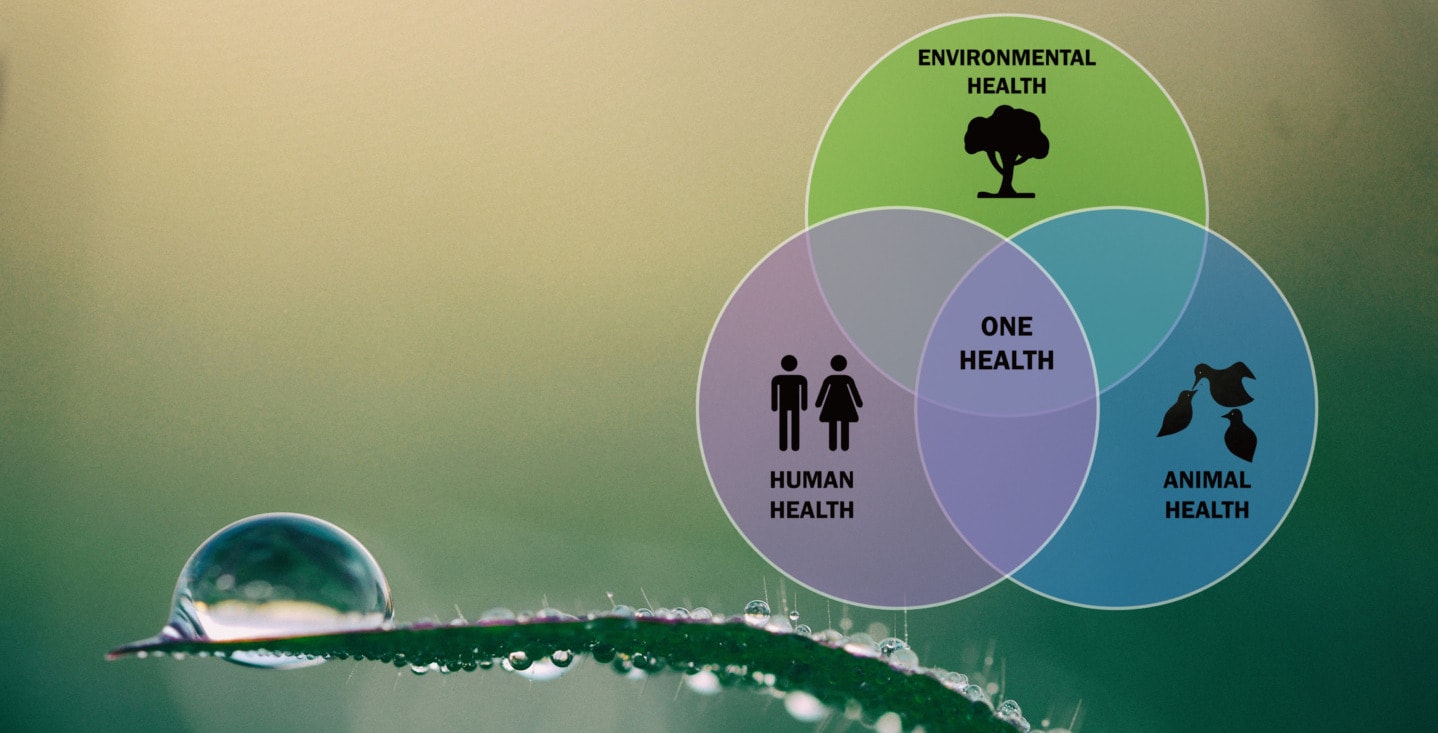

Just this year Gaspard Kerner of the Pasteur Institute examined the significant role genetic variants have played in fighting off pathogens – a battle that goes back to plagues that emerged as early as 10,000 years ago.

Through meticulous research and technological advancements, he and his team uncovered valuable insights into the human immune system’s ability to combat disease and the evolutionary changes that have shaped it.

As it turns out, it is precisely the emergence of genetic variants over the ages that provided – and still provide – resistance against certain pathogens. These genetic variants act as a key defense mechanism by outcompeting pathogens, ensuring in pandemic times the survival of those who possess them.

![[genetic adaptation infectious diseases]](https://fastcdn.impakter.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/graphical-abstract-of-Pasteur-paper-screenshot.jpg?strip=all&quality=92&webp=92&avif=80)

But genetic variants are not always present in every population. They often arise due to natural selection as a response to specific diseases prevalent in certain regions. For instance, in areas where malaria is endemic, individuals with a particular genetic variant called sickle cell trait, have a higher chance of survival. This variant alters the shape of red blood cells, making it more difficult for the malaria parasite to invade and multiply within the body.

Obviously, sickle cell is anything but a genetic charm in non-malarial countries – in fact, it is a painful and often deadly illness. But for centuries in certain areas, it helped survival.

Similar examples of genetic variants providing resistance to pathogens are found in other diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis, and leprosy. In fact, Kerner’s research identified specific genes associated with these diseases and the genetic variations that confer resistance.

These findings have important implications for the development of targeted therapies, as they help identify individuals who may be susceptible to certain ailments or who possess genetic traits that can be leveraged for therapeutic purposes.

Clearly this could play a key role in pandemic prevention plans. But it’s not that simple. According to Harvard’s Dr. Robert Shmerling, researchers have noticed the following:

- “Infection-fighting genes increased dramatically in the general population within a few generations. A change of this magnitude across a population in such a short time is nearly unheard of.

- People alive today with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus are more likely to carry those same infection-fighting genes than people without autoimmune disease. It appears that the genes that helped some of our ancestors avoid a dangerous infection in the 1300s now may be a risk factor for autoimmune disorders.”

Importantly, there are continuing efforts to analyze DNA samples extracted from archaeological remains, to identify the genetic signatures associated with disease resistance in different populations—and, just as importantly, to trace their origins.

What about COVID you ask? Our ancestors didn’t have it so we’re out of luck learning anything from them on this.

Yet, there are lessons to be drawn: From ancient plagues to modern-day infectious diseases, understanding genetic variations can pave the way for more targeted therapeutic approaches and personalized medicine.

As scientists continue to uncover more about the intricate relationships between genetics and immunity, the potential for advancements in disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment becomes increasingly promising.

Note also that new therapeutic approaches may come from unexpected directions, spurred by findings in what may ‘appear” as an unrelated field – archeology- but surely is not. Essentially it’s at the core of evolutionary genetics: rather than focusing on patients in hospital surroundings, this new field of research looks at whole populations over time to better understand evolution in general and human infectious diseases in particular.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: genetic imagery symbolizing evolutionary genetics, from joinastudy.ca