In this article by Alexandra Bulat Ph.D., a Romanian citizen who has made the UK her home we look at how xenophobia has become very common in the country.

Alexandra has completed her university studies in the UK, including a Ph.D. with Doctorate research on the attitudes towards EU migrants in the context of Brexit, comparing views in two English local authority areas.

She is the chair of Young Europeans, part of the3million, the largest organization campaigning on EU migrants’ rights in the UK. Her work is very important to understand the growth of xenophobia in the UK.

I’ll always remember the Christmas of 2018. I was on holiday and I received a message from a stranger on Twitter. I expected the person to wish me a ‘Merry Christmas’ or ‘happy holidays’, like the others. Instead, it read: ‘go back to your shithole’.

The message continued: ‘My life is short because my home is full of East Europeans and my workplace is full of East Europeans. When you all bugger off, I’ll be happy.’ It then became even more descriptive, identifying East European migrants as the source of all the problems this message sender faced in his personal life.

This was not the first or last day I received such a message. It did not surprise me in the slightest that someone could have those thoughts and voice or write them, especially on social media where we can be anonymous if we wish.

As a Romanian migrant, I have gotten so used to hearing negative views towards immigration, especially about my co-nationals, to the point that nothing shocks me anymore. It ‘became so normal and you cannot do anything about it other than laugh about it’, as one of my research participants put it when I interviewed them for my Ph.D. thesis.

I have spent my adult life in the UK and I am here to stay, regardless of whether some others approve of my presence in this country. There is and will probably always be a minority of people with openly negative views towards people like me, migrants, or people who look or sound different than them. However, it is deeply concerning when some of these views have become normalized through some of our institutions and politicians.

Anti-immigration messages are promoted right at the top of politics, even by the UK Prime Minister himself, who, for instance, suggested last year that EU migrants have overstayed their welcome. They have ‘treated the UK’ as their ‘own country’ for ‘far too long’, Johnson’s argument went on.

There’s a paradox here: politicians expect migrants to ‘integrate’, to become part of UK society. Yet, when migrants do so, they are often treated as overstepping their boundaries. They are not being ‘grateful’ to the UK enough – as some Twitter commentators try to remind me almost every time I write something positive about my migrant life. Most of all, they are not seen as being at ‘home’ in the UK – because, if they do not like something or they disagree with UK politics, they could always ‘go back home’, as some try to remind us.

We could debate what was the exact intention of Johnson’s or other politicians’ comments, but we will never know exactly what crosses their minds. However, such comments are irresponsible, particularly when coming from someone in a position of power, because they can legitimize negative attitudes which will then affect migrants’ lives directly. During the 2019 general election campaign, migrants’ rights groups spoke against such dog whistles on immigration.

The most widely spoken about example of legitimizing xenophobia is the 2016 referendum campaign, in particular, some elements of the Leave political messaging, such as Nigel Farage’s infamous ‘breaking point’ poster. My Ph.D. thesis analyzed, amongst others, a collection of EU referendum campaign materials from 2016. It illustrated how the Remain campaign almost exclusively focussed on the benefits freedom of movement brings to British citizens, while the Leave campaign had ownership of all arguments about EU citizens coming to the UK.

EU migrants were overwhelmingly portrayed in a negative light, and the so-called ‘brightest and the best’ were in a minority compared to ‘the rest’ of migrants, who needed to be controlled. Again, unsurprisingly for me, the EU migrants in need of controlling were depicted as those from ‘poor, East European countries’, as one of the leaflets explicitly underlined it. Migrant voices were absent from the debate and almost nothing and no one in the public domain offered an alternative view to negative arguments about EU migrants.

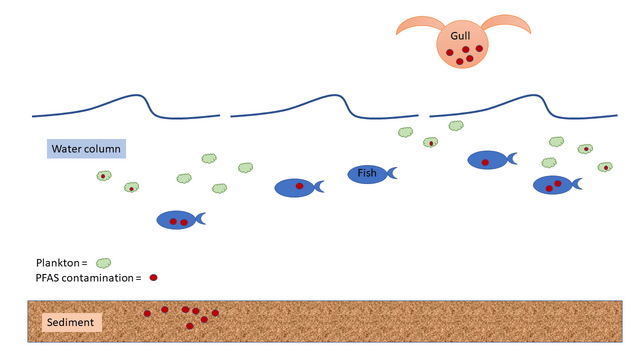

The EU referendum campaign built on a narrative that was already shaped within British society – that of the good, contributing deserving migrant and that of the bad, undeserving migrant who does not ‘contribute’. This underpinning narrative shaped some immigration policies – the effects of which we see every day. The hostile environment package of policies, implemented while Theresa May was Home Secretary, was designed to make it less ‘attractive’ for undocumented migrants to stay in the UK. Yet it created the situation where many people who came to the UK as British, part of the Windrush generation, were not only told to ‘go home’, but were forced to return to a country which most of them have not even visited for decades.

The hostile environment means that at every step in their life, migrants must prove they are deserving. The NHS, banks, landlords, and others were given the role of checking people’s immigration status every time they try to access services. The burden of proof is always on the migrant. If you cannot prove you are lawfully in the UK (even if you are), you are denied access to your basic rights. If you cannot prove yourself, you’re told to ‘go home or face arrest’ by the Home Office vans, one of the strategies of implementing hostile environment policies in the early 2010s.

RELATED ARTICLES: From Incels to Tradwives: Understanding The Spectrum Of Gender And Online Extremism |Gender As Symbolic Glue For Different Extremist Movements |What the ReOpen Protests Reveal About White Masculinity |Women and Violent Extremism |Is Brexit a Defeat for Europe? |The Wall is Everywhere – From Berlin to Brexit

I didn’t start receiving negative comments after the 2016 referendum. Through politician comments and policies, the normalization of representing migrants as not fully belonging to UK society has started long before that. The process of commodifying communities of people, making them useful ‘as long as they contribute’, also has deeper roots than the political event in 2016. Indeed, there is no doubt that the police recorded a significant increase in hate crime since the referendum campaign in which immigration was a key topic. But for many migrants, the “go home” comment didn’t occur only after 2016.

As a white Romanian, I am invisible when walking on the street, but I become visible if I walk on the street and speak English with an accent or speak in Romanian with my friends. The fact that I recently became British through naturalization does not really make a difference to the loud small minority who disapprove of my existence as a migrant in the UK.

Initially, I ignored the negative comments completely. Then, I responded to some with some banter, usually, saying that yes, I am indeed here to steal all jobs and benefits simultaneously.

But a few months ago, I read a news story about a Romanian woman being attacked in front of her house while she was simply minding her business. She was first told the classic “go back home”, then called a racist slur, then physically attacked.

I looked at the newspaper and thought, “this could have been me, or any other migrant I know.” I noticed slightly changing my behavior, checking my back when I walk home in the evening or at night, changing my accent in some situations, being more careful whether I speak to strangers who sometimes start a conversation.

In late 2019, the ONS statistics showed a ‘Brexodus’, with EU net migration that quarter at its lowest since 2003. While I want to stay regardless of the Brexit situation, it’s clear that others have already voted with their feet and left since 2016. But most migrants I’ve spoken to are somewhere in the middle.

Those who want to stay do so mostly for practical reasons. Having children in school, caring responsibilities or a partner who doesn’t speak other languages can make the move challenging or impossible. For others, leaving the UK is difficult and, in some cases, unsafe.

People also experience racism and xenophobia differently: some a lot, some a little and some not at all. I spoke to many EU migrants who were worried they may be targeted even more in the post-Brexit future. One example that stayed with me was a migrant mentioning that even his MP suggested he ‘goes home’: ‘He told me that if I was not happy, I am free to leave and they will replace me with more Indians or Chinese’.

Racist and xenophobic comments are often the final straw, rather than the main reason for migrants leaving the UK. A few left because they felt insulted by the EU Settlement Scheme, especially if they lived in the UK for decades or only knew the UK as their home. Migrants’ lives do not fit into a tick box and neither do their reasons to stay or leave.

Despite years of promises that ‘nothing will change’ for EU migrants already in the UK, we see yet more dither and delay in securing citizens’ rights. The Conservative manifesto claims the party has ‘committed absolutely to guaranteeing existing rights’, ensuring that EU migrants feel ‘welcome and valued’.

But the reality is we have to apply to stay in our homes or face deportation, something that even ministers acknowledged after months of avoiding answering these difficult questions. Those who do not apply before the deadline will be made unlawfully resident overnight. No similar scheme in the world managed to reach 100% of its audience and campaigners have warned for years that another scandal like Windrush could happen. The choice is, apply to stay in your home, in other words, prove yourself, or ‘go home or face arrest’. It all sounds like a familiar story.

A future immigration system was supposed to be fairer for everyone. Instead, migrant rights are leveled down across the board, rather than leveled up. While the ‘brightest and the best’, wealthier migrants are praised and welcomed post-Brexit, newcomers in lower-paid occupations will find it much more difficult to settle and build their lives in the UK.

I refuse to accept people who tell strangers on social media or in real life to ‘go back to your shithole’ as simply raising ‘legitimate concerns’ or ‘genuine worries about immigration’. People accusing me of a variety of things, including ruining their life because I am part of this ‘East European’ migrant group are not merely exercising their ‘free speech’, nor is any of this part of a lively debate in the ‘marketplace of ideas’.

Those keen to tell me or others to ‘go home’ are not simply engaging in a debate or conversation with people holding different views. They are actively promoting hateful speech directed to foreigners – or anyone who does not fit their definition of being British or English. Politicians, but also all of us as a society, need to draw a line between free speech and hate speech, and call out racism and xenophobia wherever it happens – including in policymaking and political campaigning.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com