Despite last year being a record year for wine and spirit exports, France’s €25 billion wine industry is under threat. As overproduction threatens winemakers’ livelihoods, especially in the Bordeaux region, the state has announced a €160 million programme to distil excess wine into pharmaceutical and cosmetic alcohol.

However, winemakers say that this is not enough to guard the industry against a repeat of the same problem in the coming years. Instead, they want to be compensated €10,000 per hectare to uproot 15,000 hectares of excess vines, which would cost an extra €150 million.

As the world’s second-largest wine producer after Italy, it’s no surprise that France carefully regulates its vineyards. A 19th-century blight of North American aphids that came with imported vines led to laws still in place today preventing European Union (EU) winemakers from using American vines.

L'exportation des vins et spiritueux est un atout immense pour la France. Nous serons au rendez-vous des mesures conjoncturelles et structurelles pour cette filière pour lui permettre de consolider sa place économique.#Vin #Innovation #Export pic.twitter.com/x4Zn4JQtIY

— Marc Fesneau (@MFesneau) February 14, 2023

Translation of the above Tweet: “The export of wines and spirits is a huge asset for France. We will be at the rendezvous of economic and structural measures for this sector to enable it to consolidate its economic position.”

France also controls the expansion of its vineyards. In 2021, the country went head-to-head with the European Commission to extend a law set to end in 2030 that caps vineyard expansion at 1% per year in each EU country to 2045.

Together with the world’s third-largest wine producer, Spain, as well as nine other countries which supported the 1% cap, France warned the Commission that “untangled deregulation would lead to an industrialisation of wine production and to the disappearance of family holdings, which knit together their rural regions.”

France’s shrinking wine market

In 2022, France’s wine and spirits export hit a record high of €17.2 billion, a rise of 10.8% in 2021.

However, this increase is buoyed by inflation, and exporting is not necessarily a viable option for smaller vineyards, even as larger vineyards transition into wine tourism.

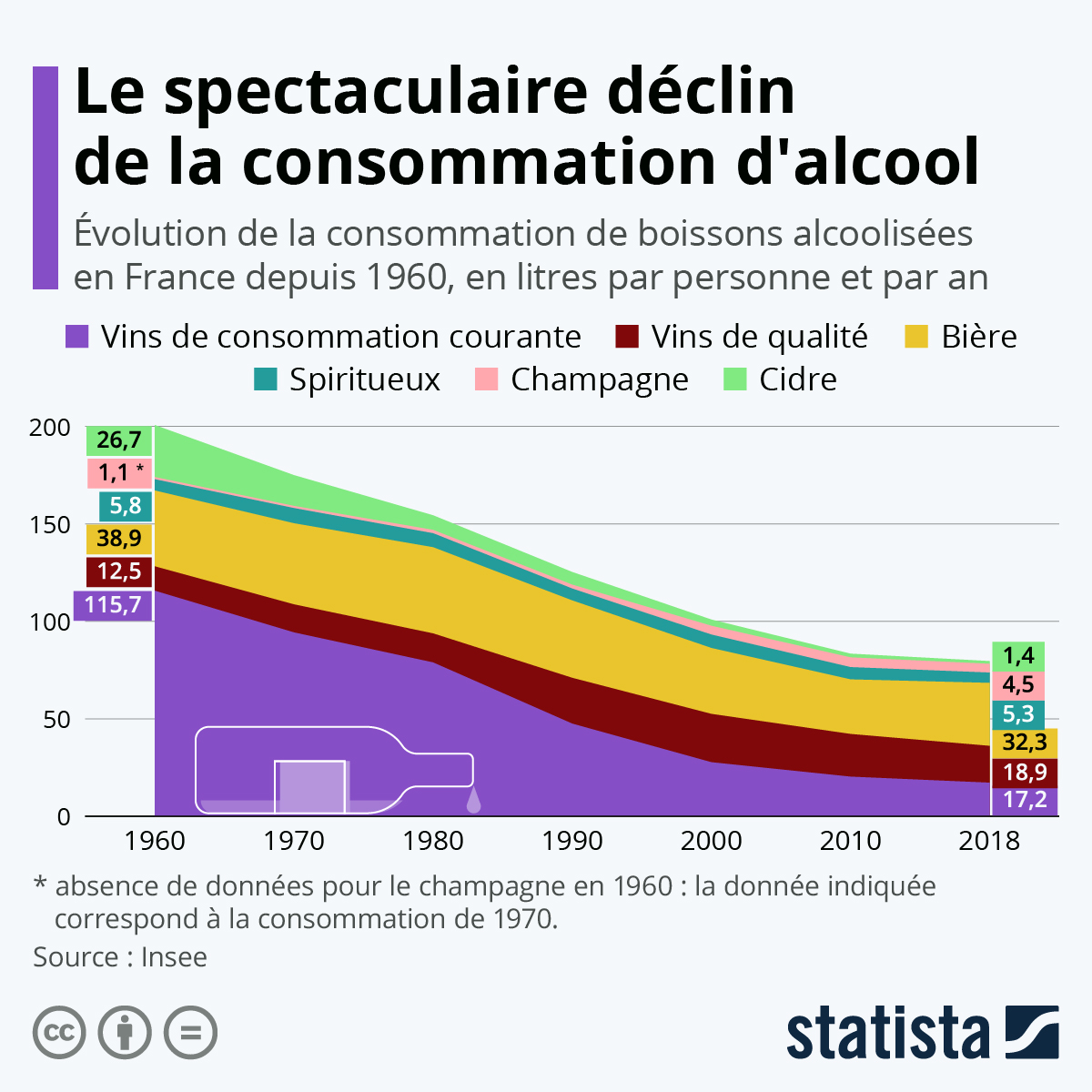

The fact is that France’s domestic wine market is shrinking: the French are drinking less wine. In fact, they’re drinking half as much alcohol in general as they were in the 1960s. For wine in particular, the decline may be steeper.

Jérome Despey, secretary general of France’s National Federation of Farmers’ Unions (FNSEA), known as Monsieur Vin (Mr Wine) to the majority of the agricultural union – believes his country was consuming “130 litres per year per inhabitant, 70 years ago,” but that now, this volume has shrunk considerably, to around 40 litres.

In the early 1950s, when French wine consumption was 140+ liter/capita, France launched the campaign "Santé Sobriété" to limit alcohol consumption. From 1954 on, graphic artist Philippe Foré designed many posters. pic.twitter.com/Jm7Cyr97Hq

— AAWE (@wineecon) January 25, 2018

What’s more, red and white wine have not been affected equally. In 2022, 15% less red wine was sold in French supermarkets compared to 2021. For whites and rosés, the decline was considerably more manageable, at 3% and 4% respectively.

For a region like Bordeaux, whose main output is red wine, this is disastrous: wine cellars are so full of previous vintages, that there is little room for new bottles.

Why are French people drinking less?

Denis Saverot, editor of La Revue des Vins de France, a well-known French wine magazine, blames “our bourgeois, technocratic elite with their campaigns against drink-driving and alcoholism, lumping wine in with every other type of alcohol, even though it should be regarded as totally different.”

Wine consumption has fallen most in the 18–35 age bracket, for whom beer makes up 39% of alcohol expenditure, while wine makes up only 27%.

Related articles: When Wine Was Healthier for You Than Water | France to Ban Deep-Sea Mining: What It Implies, and Why It’s Important | France’s Ban on Short-Haul Flights: Too Far or Not Far Enough? | The Future of Winemaking is Here

Another reason for the drop could be changing family structures and dining habits. Since the 1960s, France has seen a rise in single-parent households, of which the adults may choose not to drink alone.

Families are also less likely to eat together and are consuming less red meat, which red wine often accompanies.

The tradition of a glass of wine with each meal, therefore, is declining, much to the chagrin of French winemakers.

In providing the €160 million distillation programme, the French government is drawing on a tactic it last employed at the start of the pandemic, when restaurant and international demand for wine shrank. The capital is made up of €80 million in national credits and €80 million in EU funding to help farmers distil their excess stock into alcohol.

However, with the trend of lowered wine drinking in France continuing, this is likely only sufficient for short-term relief.

Is distilling excess wine into perfume the solution?

Distillation is merely “a little butter in the spinach,” and “will absolutely not solve the situation in Bordeaux,” says Didier Cousiney, president of the Viti 33 collective, a group of French winemakers. Ultimately, it amounts to “a few thousand euros to last two, three more months, but that’s all.”

By calling for the cull of 150,000 hectares of excess vines, Viti 33 hopes that they will prevent future overproduction and rebalance the market. Without this kind of action, winemakers like Jérome Despey of the Haurault region fear that upwards of 100,000 jobs could be lost in the next decade.

This could, however, be a difficult proposition from the French government, as EU member states are officially prohibited from releasing funds for uprooting crops. However, France is accustomed to receiving some leeway from the European Commission.

Uprooting excess vineyard would also solve a related problem.

More than half of Bordeaux winegrowers are over 50, including a third over 60, many of whom have been operating at a loss for one or more decades, and are looking to retire.

However, with sinking land prices in wine regions, many will not find buyers to take on their vineyards. Without a buyer, owners of over 3.4 hectares will not qualify for the monthly 6000 euros from the agricultural society.

Abandoning the land is not an option either: Abandoned vines are vectors for disease, which can contaminate other vineyards. Winemakers are legally obliged either to sell or grub up their land, which is an expensive process.

In this way, many landowners are tied to money pits as they seek to leave the winemaking business.

By helping vineyard owners to grub up excess vines, the French government could help release many winemakers from the shackles that their land has become, and that land could be repurposed.

Climate change: A force majeure for French winemakers

If changing internal markets and alcohol-awareness campaigns challenging winemaking traditions were not enough, winemakers now have to contend with climate change as well. And changes in environmental factors are considerably altering the taste of classical French flavours in wines.

Rising global temperatures have also led to the expansion of the wine industry in other European countries. For example, the UK now has over 500 vineyards, which are, ironically, being bolstered by French investment.

Finally, although French wine exports may have been at an all-time high in 2022, the rise in turnover was due more to inflation than production. In fact, a considerable frost in 2021 led to a smaller grape crop across the country, and volume export was actually down by 3.8% in 2022.

As climate change breeds more frequent extreme weather phenomena, French winemakers have to contend not only with changing wine culture within the nation, but also with a changing terrain that impacts the entire industry.

As the French government has worked so hard to protect its wine industry by slowing the expansion of European vineyards over the years, perhaps culling French vines is the only way to protect winemakers and free would-be retirees from the land they cannot sell, abandon, or profit from.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Hands hold freshly picked grapes. Featured Photo Credit: Maja Petric