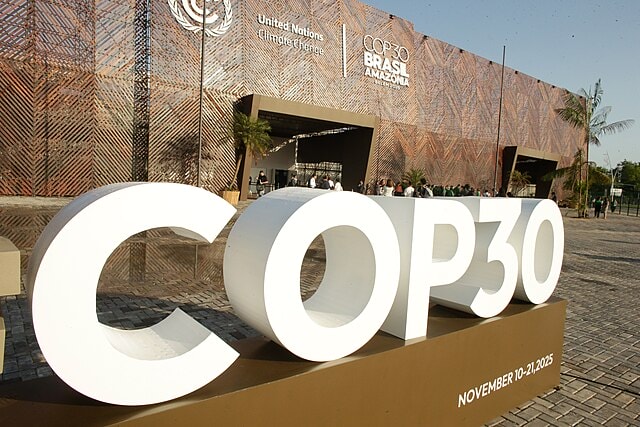

The world is watching COP30 in Belém, which has been labeled as the “Implementation COP,” a turning point at which governments will finally operationalize the promises set out in Paris. There is still room to deliver on these ambitions, but a harsh reality remains: the largest fossil fuel presence in UN climate negotiations history threatens to overshadow the talks.

A new analysis from the Kick Big Polluters Out (KBPO) coalition, a global network of advocacy organizations working to limit fossil fuel interests in climate negotiations, reports that more than 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists gained access to the conference this year. In practical terms, this means that 1 out of every 25 people attending COP30 represents the oil and gas industry. Brazil is the only country in the world that has more representatives at the conference than the fossil fuel industry. For smaller nations facing climate disasters, the imbalance is staggering.

The Philippines, still reeling from deadly typhoons, has roughly 50 times fewer official delegates than fossil fuel lobbyists at COP30. Jamaica, recovering from Hurricane Melissa, is outnumbered more than 40 to 1. The ten most climate-vulnerable countries combined sent 1,061 delegates: nowhere near the number of attendees representing fossil fuel interests.

Corporate Power at the Implementation COP

For years, climate activists have warned that fossil fuel companies treat COP as just another space to shape global policy in their favor. One example is the “Decarbonization Charter” launched at COP28, whose signatories went on to approve 65% of all new oil and gas reserves globally in 2024.

Trade associations remain one of the largest channels for lobbying: KBPO found that the International Emissions Trading Association alone brought 60 people to the conference, including representatives from ExxonMobil, BP, and TotalEnergies.

Beyond attendance, behind-the-scenes access is a powerful pathway for fossil fuel lobbyists to influence the talks. At least 599 lobbyists received Party overflow badges, allowing them to move through negotiation spaces and interact with delegates informally, often without transparency.

While COP30 is the first conference where non-government participants must disclose who is funding their attendance, this rule does not apply to people attending on government badges, creating a significant loophole. KBPO identified 164 fossil fuel lobbyists within official delegations, including 22 from the French delegation (five from TotalEnergies) and 33 from Japan’s delegation.

Brazil’s Controversial Guest List

The host country’s own invitations stirred additional backlash. Brazil placed the Batista brothers, owners of JBS, the world’s largest beef producer, on its official “VIP list,” giving them access to the COP30 Blue Zone. The Blue Zone is the restricted area of COP30 where diplomatic negotiations take place and decisions are made.

JBS has been repeatedly fined for environmental violations and has been linked to cattle sourced from illegally deforested land in the Amazon. Their presence, alongside representatives from Petrobras, ExxonMobil, Vale, and other major mining companies, underscores the close ties between Brazil’s economic elite and the climate negotiations.

At the same time, Brazil’s Indigenous communities received only a fraction of the access. A record 2,500 Indigenous Brazilians traveled to Belém, but a battle remains in the fine print. While this is a large number, the KBPO investigation found that only 14% of indigenous attendees managed to secure the Blue Zone accreditation that many fossil fuel lobbyists hold at the negotiations.

Attendance is certainly better than nothing, but without the Blue Zone accreditation, the ability to influence outcomes at COP30 is severely limited. The groups protecting the Amazon have limited access, while the industry leaders most responsible for deforestation and emissions remain at the center of negotiations.

“Every COP we allow dirty industry representatives to attend in their droves incurs a debt that will be paid in future climate disasters. They are a tiny minority of Earth’s people; we are the vast majority. We need polluters out, people in at COP.”

— Patrick Galey, Head of Fossil Fuel Investigations at Global Witness.

Indigenous Demands: Land Demarcation as Climate Policy

Brazil’s Indigenous leaders arrived at COP30 with a primary demand: that Indigenous land demarcation be formally recognized as climate policy, both in Brazil’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and in global negotiations. Indigenous-managed territories have much lower deforestation rates and stronger long-term ecosystem protection, and officially declaring land as Indigenous Peoples’ is one of the most effective natural climate solutions.

Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, echoed this priority in the opening plenary, calling on world leaders to recognize Indigenous territories as essential climate mitigation tools. However, Indigenous leaders argue that symbolic recognition is insufficient, and they believe they were not granted genuine negotiating power at the summit.

“Ideally, we would participate as negotiators inside the official delegation. That would make this a different COP.”

— Toya Manchineri of the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon.

Geopolitics Overshadowing COP30

Meanwhile, Australia and Turkey are in a diplomatic contest over who will host COP31, a dispute that has increasingly overshadowed the climate talks currently underway. Instead of channeling political energy into securing stronger emission-reduction pathways or scaling climate finance, governments are fighting over regional influence.

As noted by David Dutton, director of research at the Lowy Institute, “[a]ll the effort has been around the bid and not so much about what you’re actually going to do to sustain climate momentum.”

The controversy highlights a deeper problem: COP now functions as much as a geopolitical arena as a climate forum. Meanwhile, global emissions continue to rise, climate impacts intensify, and the world edges closer to irreversible tipping points.

Rebuilding trust in the process requires shifting attention back to the negotiations themselves and establishing clearer, firmer rules to limit the sway of fossil fuel lobbyists whose presence has continued to increase in recent years. The logic is clear: Industry leaders cannot hold outsized power at the very conferences tasked with regulating them.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of impakter.com — Cover Photo Credit: UN Climate Change / Kiara Worth.