Over the past 100 years, agro-biodiversity has steadily disappeared with the adoption of modern agricultural practices and the globalization of the food system and marketing.

Something has gone seriously wrong with agriculture worldwide.

Every year local land varieties and landraces are lost, livestock breeds are at risk of extinction and, on average, six livestock breeds are lost each month. As of now, some 75 percent of the world food comes from only 12 plants (mostly rice, maize and wheat) and five animal species. More than 90 percent of crop varieties have disappeared from farmers’ fields. In fisheries, all the world’s 17 main fishing grounds are now being fished at or above their sustainable limits.

Who says so?

FAO itself . The data comes from one of its technical units, and the report actually dates back to 1999, see here. Since then, as we all know, nothing substantial has been done in any country to reverse those trends.

Should we worry in this day and age when scientists predict the Sixth Extinction is upon us? Are scientists kidding us? Has FAO even raised the alarm?

Take a look at FAO’s most recent program of work (for 2014-2015). Here is a summary of the main goals presented by the FAO secretariat and approved by FAO member countries:

- fight hunger;

- make agriculture sustainable, promoting “evidence-based” practices without damage to the resource base;

- reduce rural poverty and create employment;

- help to build safe and efficient food systems;

- increase resilience of food and agricultural systems.

The goals are the same as ever, reflecting an over-riding concern with fighting hunger, exactly as in the days FAO was born. The ambiguity in the name – the tension between food and agriculture-related activities – continues and for the moment, food concerns prevail over agriculture.

***

In the video: Agricultural Cooperatives.Key to Feeding the World. For people working in all areas of agriculture, all over the world, cooperatives and producers’ organizations give their members a voice and promote peace in the community. And by marketing almost half the world’s agricultural output, cooperatives boost food production and incomes – and the global economy.

***

Perhaps the only consolation is that attention to the needs of smallholders remains unaltered: small farmers are still at the center of FAO’s concerns. Small farms – mainly subsistence farming in developing countries – continue to be a major target group for FAO policies; for example, the process of strengthening food systems (goal #4 above) should be carried out not in favor of major global corporations but safeguarding smallholders.

Notice also the new buzz word: “resilience”. Ever since the Brundlandt Report made the concept of “sustainability” famous in the 1980s, re-defining what development means, no program of work of any UN agency can do without it. And now we have a brand new concept, resilience, originally applied in the context of disasters, it is meant to reflect what is needed to withstand disasters and recover from them – and it is fast entering other areas as well, including “normal” development. With climate change that causes a higher frequency in natural disasters and the constant local wars affecting fragile states around the world, expect the concept of “resilience” to become ever more popular. For development efforts won’t be successful unless they are both “sustainable” and “resilient”.

Does that answer the real challenges we are facing on a global level?

No doubt FAO is responding to the need of the Third World to focus on agricultural development and feeding the poor – those are very real needs.

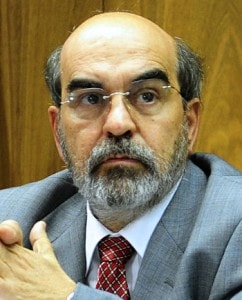

In the photo: José Graziano da Silva,current Director General

The latest FAO program of work, developed by the new Director General, José Graziano da Silva (from Brazil), is very much in line with the policies of the last two Director Generals, Saouma (from Lebanon – 1976-1993) and Diouf (from Senegal, 1994-2011), in the sense that the overall direction remains the same – essentially policy support for the “fight against hunger”.

As of now, FAO’s most concrete actions consist in helping farmers recover from disasters – for example it recently sent seeds and tools to the war-torn Central African Republic. Deliveries began in April 2014, and six weeks later some 12,000 farm families had received “agricultural kits” consisting of 25 kg of seeds and two hoes. This is fine, but surely, a highly technical agency like FAO could do more?

In the photo: IDP Camp at M’poko Airport, Bangui. A family in the camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) located at M’poko Airport in Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic. 06 June 2014. Bangui, Central African Republic.

In the photo: IDP Camp at M’poko Airport, Bangui. A family in the camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) located at M’poko Airport in Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic. 06 June 2014. Bangui, Central African Republic.

How FAO operates in non-emergency areas is best exemplified by the Alliance Against Hunger and Malnutrition, established with FAO support in 2003. This is precisely what its name says, an alliance – a coordinating effort to link in a range of anti-hunger development initiatives the major players at every level: a the top, various concerned UN organizations and not just FAO and national governments, at the bottom, NGOs operating at field level.

What do they do? For example, they discuss the need for nutrition education and for targeting lactating women and primary school children etc. Subsequently, some local institutions volunteer to do something, and someone at times locally, at times internationally, provides the needed funding. No doubt, all very laudable efforts.

But what about the real issues facing humanity? Issues like the extinction of biodiversity or the wave of obesity that has plagued the developed world. These issues get very little policy attention from FAO, beyond an occasional symposium of experts (like the one on “biodiversity and sustainable diets ”, held in 2010).

In the photo: Secretary-General Meets Ed Norton, New Goodwill Ambassador for Biodiversity. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (left) meets with actor Edward Norton (seated right), newly-appointed UN Goodwill Ambassador for Biodiversity.08 July 2010. United Nations, New York. (source UN / multimedia)

In the photo: Secretary-General Meets Ed Norton, New Goodwill Ambassador for Biodiversity. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (left) meets with actor Edward Norton (seated right), newly-appointed UN Goodwill Ambassador for Biodiversity.08 July 2010. United Nations, New York. (source UN / multimedia)

FAO is also absent from other areas where one might have expected it to act as a leader and rallying point. For example, its stand on biotechnology is little known and understood (divulged once, some ten years ago, it got an angry response from non-OGM supporters) and no meaningful technical debate was ever started; in the area of agricultural trade, its role is limited to the provision of statistical information and political decision-making falls within the purview of the World Trade Organization.

What has happened is that FAO is being marginalized on every front: it is pushed into activities that are exquisitely political while concrete technical issues – such as the loss of biodiversity – are downplayed or set aside.

As of now, FAO is expected to provide fora for food discussions and coordinate other aid agents rather than acting as an aid agent itself. Back in the 1970s and 80s, FAO used to successfully implement projects to test new or improved production methods and illustrate the way forward to local farmers. Why not do it again? Instead it functions as a “coordination” unit, letting others “do things”.

Issues are watered down

For example, a major issue like biodiversity is linked to other issues like gender, as was done in the LinKS project in Southern Africa financed by Norway. It operated in three countries (Swaziland, Tanzania and Mozambique) and ended in 2005 after seven years of operation with few results: it reportedly increased the importance of “awareness of indigenous knowledge” among development specialists in all three countries and contributed to the reformulation of a livestock policy for Tanzania.

What is needed is a little less talk and more action in the areas that matter most to the future of humankind.

Re-positioning FAO away from fighting hunger – which, strictly speaking is the World Food Programme’s mandate – would help revive FAO. It would make it more relevant to humanity’s most pressing needs in terms of survival of the species. It would also help make the best possible use of FAO’s technical capacities and ensure that the organization remains useful for a long time to come, at least for the rest of the 21st Century.

In the cover photo: Secretary-General Visits Sustainable Agriculture Project in Benin. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (front, grey suit) is guided through Centre Songhai, a non-governmental organization specialising in research, training and development of sustainable agricultural practices, in Porto Novo, Benin. 13 June 2010. Porto Novo, Benin. (source UN / multimedia)