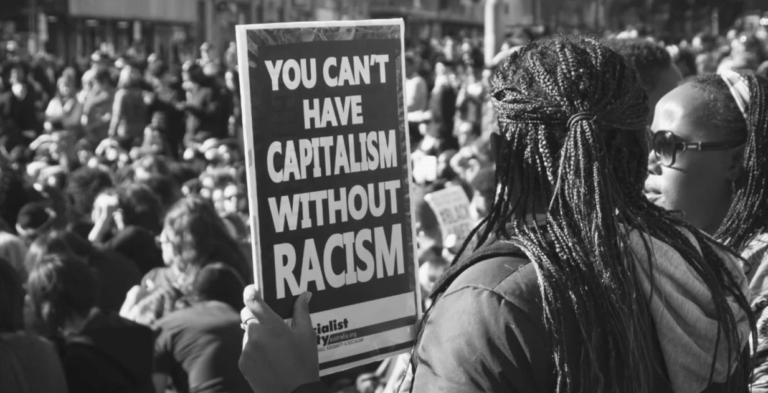

Unpacking the ideology which drives neoliberalism can be informative in understanding why white people often do not feel guilty about racism: This is why whiteness does not take more accountability and action in dismantling racism.

Every man is the architect of his own fortune.

There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women… People must look to themselves first. It is our duty.

– Margaret Thatcher

You may be appalled by such egocentric affirmations, yet this is the way of life in a neoliberal era – freedom and individualism are highest on the agenda. In case you have not encountered the term ‘neoliberalism’ beforehand, it is prudent to define its parameters.

According to Matthew Eagleton-Pierce, the neoliberal ideology was formally introduced in the 1980s. He defines it “as a system of enhanced capitalist powers,” where marketisation, commodification, competition, and the idealised sense of the free individual is key.

Neoliberalism is the pervasive ideology of today and its effects are ubiquitous – social inequalities, a dominating finance sector, privatisation, deregulation and so on. It is our current fabric of life.

You may know neoliberalism’s predecessors: Margaret Thatcher, Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek – these are just a few of its advocates. Hayek’s logic convened that collectivism is totalitarian. Instead, the individual should be free and allowed to compete independently.

Intuitively, forces of competition would co-ordinate the individual, the rational homo economicus, to act out of self-interest thus ensuring the best possible outcome. As individuals are different with different needs, there is no general welfare.

Subsequently, individual needs are supreme. Social ends equate an aggregate of identical individual ends whereby common action will only occur if it serves one’s desires, and, sometimes, collective purposes.

Later, Thatcher reintroduced Hayek’s vision, yet in the rhetorically compelling manner that only politicians can perfect. She considered society a “living tapestry of men and women… the beauty of that tapestry and the quality of our lives will depend upon how much each of us is prepared to take responsibility for ourselves.”

Every individual is talented, the state should simply facilitate the environment – a milieu of meritocracy and competition, she conveyed in an interview. Thatcher envisioned society as a composition of “inter-dependent social systems and institutions.” This structure “allows” individuals to express individuality and autonomy, which in return shapes these institutions.

Hayek and Thatcher encouraged competition and the idealised free individual. Across the Atlantic, Friedman and Reagan introduced the economic means materialising neoliberalism. In a New York Times attribute, the CEO, Marc Benioff, outlined Friedman’s economic “myopia” as the following: “Our sole responsibility to society? Make money. The communities beyond the corporate campus? Not our problem.”

In the Friedman Doctrine, society should reintroduce the “socially destructive ‘monomania’” inherent in fundamentalist capitalism, where only profits matter and “any virtuous act by businesses beyond what the law requires is simpering folly.”

Friedman’s creed of competition and profit-maximization sustained until Reagan was facing a “crisis of competitiveness.” But the solution was simple: tax cuts for high earners, strict monetary policies and deregulation. Yet, as imaginable and currently visible, this trend transcended through decades leading to a concentration of power and wealth.

Neoliberalism became an aid to capitalism – an ideology of capitalist power, competition, and financialisation. The vitality of neoliberalism would thus best endure through the idealised sense of the free individual. Existing as part of a tapestry of individuals composing our system, one should simply pursue a self-interested, rational behaviour, and the collective health would sustain.

Behind rhetoric, hidden by ideals of competition and the empowered self, the tapestry is, in reality, a burnt poster depicting one human race stomping on one another to reach for the top – or even just the chance to get by for another day.

The ramifications of neoliberalism have become undeniable. Noam Chomsky said, “if you ask yourself what this era is, its crucial principle is undermining social solidarity… It’s not called that, it’s called freedom.”

Individual freedom equates a private, severed life. Privatising every aspect of life naturally diminishes the necessity of collectivism. But without social solidarity, accountability towards others and society itself fades behind the forced incentive of self-interested behaviour – it becomes the individual before the community.

Related Articles: Racism in My Relationships | Black Women Matter | Resources to fight Racism | BLM Protests target City Governments

Neoliberalism, Individualism and Persistent Racism

So, what happens when “race” emerges on the poster? You may know the answer: “All lives matter”, “I had the same privileges that the other guys had”, “slavery happened years ago, what does it have to do with me?”, “I don’t see colour.”

As whiteness conceives itself as self-interested, rational individuals who compose the system, and alongside a tenacious testament of anti-racism, the existence of a racially oppressive system is inconceivable.

The Discourse of Individualism allows whiteness to exempt itself from patterns of racial discrimination, Robin DiAngelo explains. She claims that, individualism positions whiteness “as a unique entity – one that appears to have emerged from the ether, untouched by socio-historic conditioning – rather than as a social, cultural, and historical subject.”

But, as Sara Ahmed said: “history is what we receive upon arrival.” It is our gift, something given to us upon our entry into this world, and thus, no one emerges as severed individuals independent of their past or present environments. We are connected to everything and everyone.

Neoliberalism’s endurance of individualism and competition mitigates the socio-historic schema. A historical schema, which “the white man [who] had woven [me] out of a thousand details, anecdotes, stories,” Frantz Fanon explained in his analysis of blackness.

He revealed the existence of a corporeal schema, a thematization of blackness, which had been socially authored by whiteness through history. As an outsider inside the white world, Fanon narrated: “I am the slave not of the idea that others have of me but of my own appearance… I am being dissected under white eyes, the only real eyes. I am fixed.”

Without attention to history and legacy, whiteness and its individualism will never grasp its connection to the past and current black struggle.

James Cone, founder of Black Liberation Theology, once wrote “there will be no peace… until white people begin to hate their whiteness.” Rooted in Christianity, Cone believed that black anger and white guilt were key components of the black liberation.

Today, we evidently see black anger, but white guilt is absent. Why should whiteness even feel guilty when its legacy is a story of success rather than a history of racial oppression and exploitation?

Neoliberalism is the total absolution of white guilt. We are disconnected from our past and others. We create our own fortune, so if you fail that is on you, as an individual. Your success is detached from your past, your present environment, and your next-door neighbour.

The outcome: Whiteness rejects accountability, responsibility, or even remorse for its white legacy of slavery and subsequent racial suppression up until the present day. It happened in the past, so what does it have to do with me today? Everything. It is the white legacy.

However, since the neoliberal ideology is the accepted doctrine in a white society, let’s then reintroduce its fundamental thought: the aggregation of different individuals shapes the system.

Strong individualism impedes accountability and social solidarity against racial injustice. But without accountability for the past and present realities of racial discrimination, exploitation and exclusion, whiteness will not feel the necessary guilt and commitment to change

So, if we, individually, make up the system, aren’t we then a part of the problem? Strong individualism impedes accountability and social solidarity against racial injustice. But without accountability for the past and present realities of racial discrimination, exploitation, and exclusion, whiteness will not feel the necessary guilt and commitment to change.

- Watch – A Conversation on Race and Privilege with Angela Davis and Jane Elliott

- Read – Jane Elliott – Commitment to Combat Racism

- Read – University of San Francisco’s recommended links for anti-racism

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com

In the Featured Photo: World Trade Centre, New York. Photo Credit: Kathrine Kallehauge

You can find Kathrine on Twitter or Linkedin.