The 2019 European Parliament elections mark a real watershed for Europe. We are in new territory. European politics will never be the same again. Where there was at best indifference to the dream of a United States of Europe, there is now enthusiasm. And interest in reforming the European institutions to make them work better and bring them closer to the people.

Paradoxically, this upsurge in “more Europe” (to use Merkel’s term) is the result of the populist-nationalist- sovereignist parties’ own campaigns across Europe. With an explicit agenda to undermine European institutions and turn the clock back to the 1960’s – to a De Gaulle vision of a “Europe of Nations” stunningly unsuited to a globalized world, whether one likes globalization or not – they scared people into voting against them. Europeanists, already shocked by the Brexit mess, could not allow them into the control room of either the EU Parliament or the EU Commission.

Populists are both winners and losers in this election: they gained votes but not enough to get into that control room. They are certainly here to stay but they also hit a glass ceiling that they are not likely to ever break through. Because, policy-wise, they bet on the wrong horse: migration instead of climate change. And on migration, they are not able to offer a solution. It is a divisive issue for everyone, populists included. While climate change concerns everyone and the solution exists: Containing greenhouse gas emissions and working towards a sustainable circular economy is something everyone can embrace.

Here is what happened and why it’s a watershed.

An Unexpected High Turnout

Turnout has never been higher in decades:

Turnout was the first inkling we had that something big was brewing.

Decline of Traditional Centrist Parties

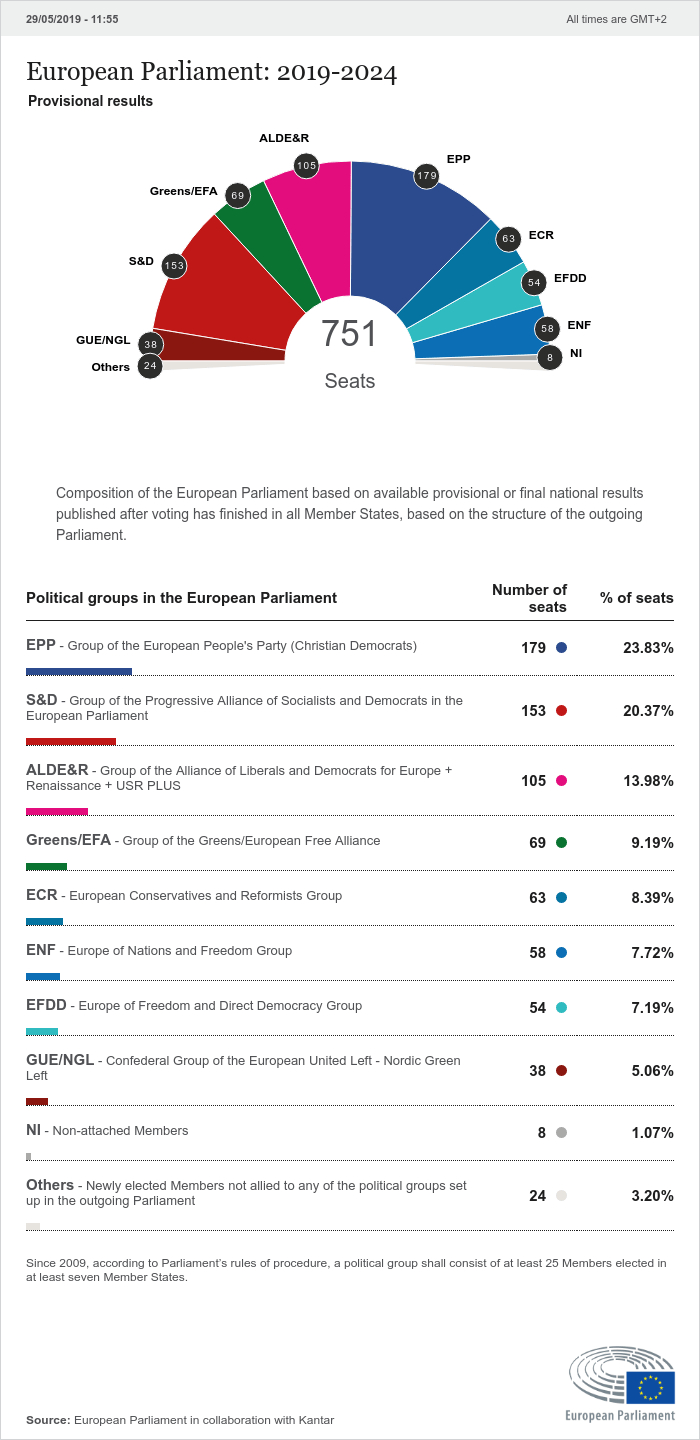

For decades the European Parliament has been “run” by two large groups at the center. One on the left with a socialist footprint S&D; the other on the conservative/moderate right, the EPP. And now the third largest group, ALDE has an addition, Macron’s Renaissance party.

S&D and EPP (and, to a minor extent, also ALDE) echoed the strength of established centrist parties across Europe. No more. They are now displaced by new and rising nontraditional parties, populists on the right and greens-ecologists and liberals on the left.

Germany is the country where the change at ground level played out in a most striking way. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s governing coalition came out of the vote seriously weakened, raising speculations about its future. The chancellor’s party, the Christian Democrats, lost five seats, earning only 28.9 percent of the vote. Their partner in government, the Social Democrats, collapsed, coming in at only 15.8 percent.

The Greens did very well, becoming the main party on the left with 20.5% while the populist Alternative for Germany did relatively poorly, coming in at 11%, less than the 12.6% it got in 2017 in the national elections.

The Rise of New Pro-Europe Parties: The Greens, the Socialists and Volt, the New Transnational European Party

This is what really changed the game – far more than the populists. For the first time, there are large numbers of people who want to change Europe and change it for the better. Three of those pro-Europe parties stand out: the Greens, the Socialists and Volt, a new political animal never seen before on the European scene, the only party that is transnational and has run in 8 different EU member countries.

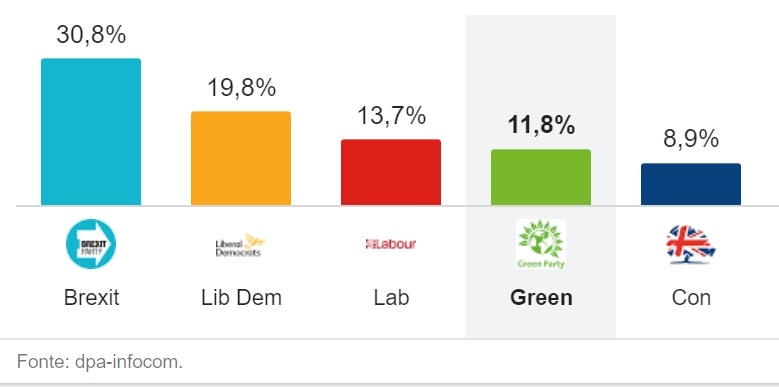

The Greens are everywhere, from Germany to the UK and France where they placed third, behind Macron. The UK in fact is a bit of a special case. In spite of the stunning result of the Brexit Party, the Greens are doing very well, just behind Labour and way ahead of the Tories:

The effect of the European vote on UK internal politics deserves an article on its own, but it is clear that the Brexit Party result will only delay the solution to Brexit – unless Labour finally decides to face the issue and call for a second referendum.

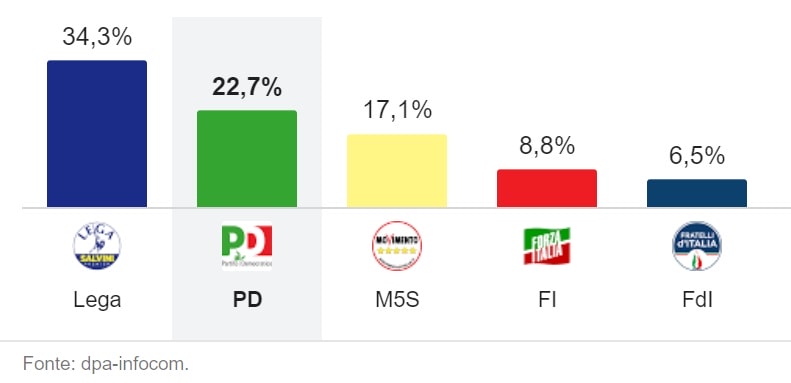

Perhaps what is most remarkable is that there is no Green party present as such in Italy. Here the politician that made the strongest showing against the populist Euro-sceptic government (Salvini’s League and Di Maio’s Five Star Movement) was Carlo Calenda (PD) whose European manifesto aligns of course perfectly on all main issues, climate change included, with the liberal, socialist and green formations found in other countries. Notably with Spanish Premier Sanchez’ Socialists.

Spain’s Socialists have had their largest win ever, turning it into a remarkable Socialist success compared to the rest of the continent. According to preliminary results, the Spanish Socialists secured 20 of the 54 seats granted to Spanish lawmakers within the European Parliament, up from the 14 seats they previously held. Mr. Sánchez told supporters, “We will construct a social Europe”.

What is interesting is the shape of the “vote of the future”: Many of the pro-Europe voters were young, and perhaps there is no better example of this surge of support for Europe among the younger generations than the rise of Volt. Volt is historically the first ever political formation to run a pan-European campaign in various EU member states, all under the same party and political program. Volt ran in 8 countries and even though the party is very new (it became operational only last year), they got one MEP in (Boeselager for Germany) and respectable results in Luxembourg (2.11%) and the Netherlands (1.9%).

Populists Here to Stay But On The Margin

Results in the Visegrad group of countries were just as expected, with populists coming on top (for example, Hungary’s Orban got over 52%). There is no doubt that the Macron-Le Pen battle mesmerized observers. Yet Le Pen won just barely, by a small percentage point, 23.3% vs. 22.4% as she was able to capitalize on the Yellow Vests protests that had weakened Macron. As expected, the biggest success in Western Europe for Populist-sovereignists was in Italy with Salvini’s League obtaining 34.3 percent – largely as a result of the collapse of the Five Star Movement (17.1%) that has disappointed its base.

There are several reasons why populists-sovereignists are likely to find it hard to expand.

Populists have a forma mentis, a turn of mind that makes them long for the past. A destructive nostalgia that rejects the world as it is and dreams of a 1950’s Europe that no longer exists. They enthusiastically embrace the Trumpian example of My Country First without realizing the danger. They don’t understand that no single European nation can withstand the two world powers, China and the United States, on its own. Only a United Europe can.

Likewise, following Trump’s example, they deny climate change. This means they are out of the main political debate that concerns the new generations, as Greta Thunberg has so well exemplified.

Aside from their anti-Europe agenda, populists cannot agree on most major issues among themselves, starting with migration. Italy’s Salvini wants Europe to take in migrants on the basis of national quotas, Hungary’s Orban, determined to keep his country closed to immigrants, won’t hear of it. Relations with Russia are also a sore point, France’s Marine Le Pen and Italy’s Salvini feel friendly to Putin, Poland is dead set against him.

Their numbers have risen, but they are still in the minority. The best the populists can hope for is to have around 150 MEPs. But operationally, given their internal dissensions, the number is more likely to be a lot less than that, probably half, that’s around 10% of the European Parliament. Not enough to achieve anything at all.

How the Vote Changes the European Parliament

In the new European Parliament 2019-2024, the center that used to be dominated by the EPP and S&D is more fragmented than before. For example, the S&D is smaller than the EPP but the Greens/EFA and the S&D together, with 218 MEPs, are larger than the EPP or the ALDE&R on their own. In short, the Greens could hold the balance of power ans swing it in their preferred direction. It is clear that the new groups at the center and left – from EPP to S&D – will need to work together.

Expect those large groups to cooperate on European issues since they are all pro-Europe – in contrast to the populists-sovereignists, likely to find themselves stuck in internal bickering. And who are in a decided minority.

What Next

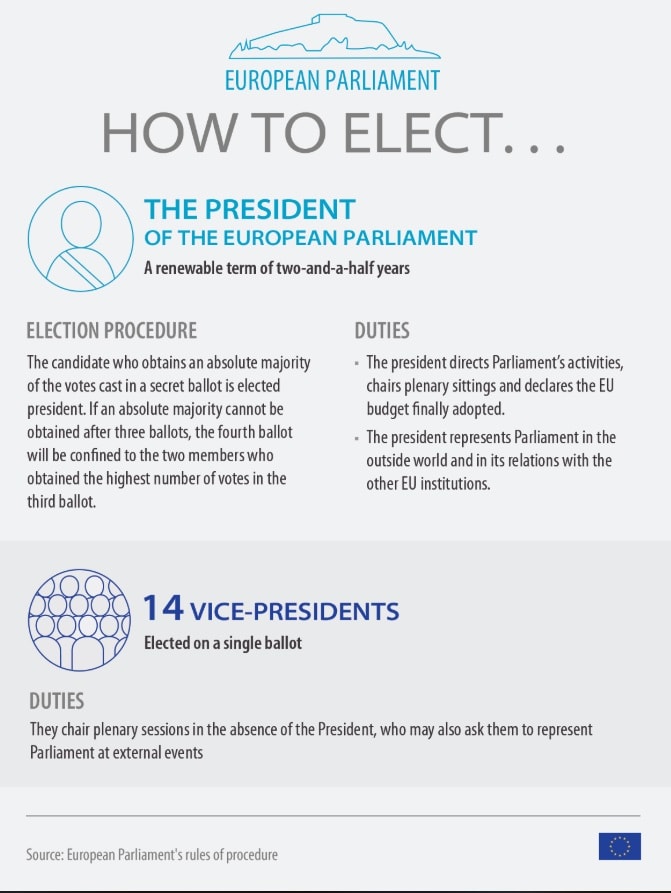

The process is complex and long.

For the President of the European Commission and Commissioners, the process is also equally long and political. Here is how it works for the President of the Commission:

All this takes time, the new Commission won’t come in before November. Given the changes in the new Parliament, expect that a candidate like Weber, the EPP candidate, will have a more difficult time than expected, now that his group has lost momentum. Macron and Merkel disagree over who should be the new EU leader. Many are speculating that the highly visible and successful EU Commissioner for Competition, Margrethe Vestager (of the ALDE group) might be the candidate with the best chances.

Stay tuned.

Featured Image: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2019 – Source: EP