Travels, stories, danger, touching moments, and profound experiences are the threads that weave the life of Duilio Giammaria. A fascinating person and a courageous correspondent that has strived to report unbiased truths about the world to his audience throughout a 30 year career. This interview will take you through the life journey of a man that has lived through war, yet is inspired by beauty and whom Impakter was honored to interview.

Q: How did Duilio Giammaria become Duilio Giammaria the war correspondent?

A: I had the sudden opportunity to become a war correspondent in Beirut in 1989. It was an amazing experience, tragic and beautiful at the same time. If you have never encountered war, it strikes you deeply. War has its own aesthetic. In war, everything transforms, takes a new form and becomes more essential. Beirut was my first experience. Then in 1993, I went to follow the war in Sarajevo for an extended period of time, and there my interest for war solidified. Being a war correspondent is a personal and intellectual challenge. You have to put several things on the line: your courage, your fears and especially, your intellect. You must be constantly aware of where you are going and why. Anthropologically speaking, war is also very interesting, having to incessantly question: Can I trust this person? What is he telling me with his body language? What can I understand from what they are saying to me? Are they voluntarily telling me something I didn’t ask for? And nonetheless, often you have to trust people. War is dangerous but a lot adrenaline serves as an antidote to the risks. This electrifying feeling, rarely experienced in everyday life, attracted me towards this career. Knowing that you never have the “right” source is another very stimulating thing. When you are in the epicenter of the facts you have to very quickly form an individual judgement – lacking a hypothesis to verify at that point. You are the first witness to facts that you quickly have to discern, interpret, and transmit to the world. You are on the forefront of facts and no one other than yourself can tell you exactly what is right to do at that particular moment. For a journalist war is like the Formula One for a pilot.

Q: You mentioned that war is very interesting anthropologically speaking, tell me a bit more about this point of view.

A: I studied a lot of cultural anthropology which helped me understand the different nuances of human behaviors. While reporting in faraway countries undergoing a war, it is essential to go in depth. You have to profoundly understand the specific community of people in front of you. In such places, there is propaganda and a sort of smokescreen everywhere. It must be crossed in order to get to the real facts and to understand the true motivations of the individuals in front of you. Why are they killing each other? Are they pretending it is because of religion? Maybe not. Often times you have to consider if your presence in a place is influencing the situation. Cameras, reporters, etc. can cause a bias in the behavior of people. So you have to dig even deeper to truly understand the motivation behind of the facts. Paradoxically, this gives a sort of sense to my work, trying to decipher the truth in a cloud of smoke.

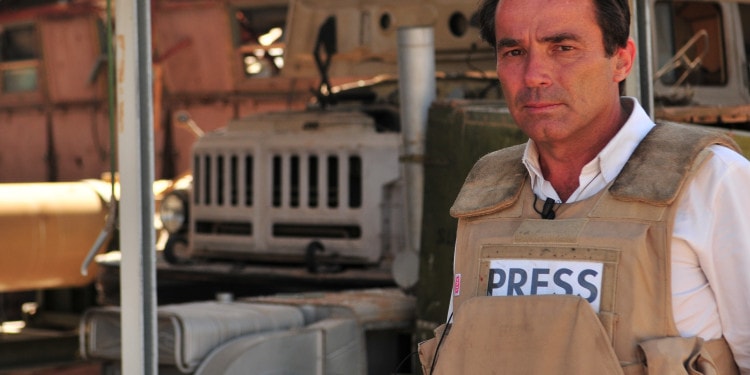

In the photo: Gilles Jacquier, my dear friend, who died from a grenade attack in Syria in front of his wife. We covered the war in Libya together

In the photo: Gilles Jacquier, my dear friend, who died from a grenade attack in Syria in front of his wife. We covered the war in Libya together

Q: During the crucial moments when you are in the front line, how are you able to report the “truth”?

A: You have to remain an outsider observing the facts. Drawing your own boundaries and giving a certain weight to all of the information you are collecting is imperative. Multiple and diversified sources are essential in helping you to cross check the information. From children on the street (whom often say strategic truths with their spontaneity), to the chief of a village. The closest version of the truth always comes out by analyzing different layers of understanding. I see it as a wafer – layer one, layer two and so on – then you take a cross section into the whole wafer and maybe you get closer to the truth. However, sometimes you don’t and it is important to report with a bit of doubt. Considering that journalism is the high witness in the facts of truths is a bit mystified and erroneous. A journalistic piece should always finish with an interrogation point. You have to reveal your own doubt and be transparent with your audience. Transmitting to them that maybe you didn’t get it completely right is important. It is good to challenge them, while letting them know that you did your best but you are not all- knowing. A journalist is only a witness.

Q: What makes you wake up and do this job every day, often times risking your own life?

A: The fact that I finished the day with doubt makes me wake up every day wanting to check that doubt and find another path towards the truth. With this job, I have come across huge difficulties and seen immense suffering but it is very important to not internalize this suffering. I have to keep my distance to be able to report in an unbiased way. Otherwise, I risk experiencing the Stockholm Syndrome – when you are surrounded by certain people in a certain situation and you start becoming like them. In war, both sides tell you that the other is the enemy and it’s important to stay neutral to avoid exposing a thesis a priori. I can expose a thesis only if I have crossed the front line and seen the other side as well. Feeling challenged and overcoming difficulties is another motivation. For instance, I think to myself: “Will I be able to cross the border?” “Will I be able to get to the front line?,” “I know if I can get there and cross it, I will be able to tell a story and witness something for the first time in my life.” A very difficult and interesting task to accomplish. I like challenges and it is my immense curiosity that moves me. It is an automatic behavior of mine to always go in search of these sorts of experiences.

In the photo: On the Nassirya runway, a few days before the Italian military arrived in Iraq

In the photo: On the Nassirya runway, a few days before the Italian military arrived in Iraq

Q: Having spent so many years in Afghanistan and Iraq, do you think these countries will ever be able to recover from the aftermaths of war? What is your outlook for their future considering ISIL?

A: Quite honestly, I don’t see any end to the conflict yet. In Afghanistan, I think they are consumed by violence and it will stay like that for at least another five years until the Taliban takes over. The president of Afghanistan is trying to enable the Taliban to politically express themselves. But politics are war done in a different way. If the Afghans were in a vacuum within a few months they would be able to restore a peaceful situation. But they have Iran and Pakistan – a constant source of tension as they sponsor the Afghan Taliban. Then there is also America and China. It is as if globalization and geopolitical forces brought on the conflict upon this country and they make it very unstable. Afghanistan was a country isolated from the world for centuries. Not because it closed itself to the world but because it was far away and no one went there. Suddenly, in these valley where tribal people lived, ferengi (the term Afghans use to identify foreigners) appeared. Foreigners, especially the British, created the rules of this violent game of “I give you the guns to combat the ‘enemy’.” And this created the dichotomy of the friends of the farengi fighting against the rest with the arms given to them by the foreigners. It is very difficult to stop this dynamic now.

In the photo: A women at the market. Burkas remain mandatory for the majority of women in Afghanistan.

In the photo: A women at the market. Burkas remain mandatory for the majority of women in Afghanistan.

For Iraq it is an even more complicated situation. ISIL has taken over Ramadi, an important city 130 km from Baghdad and the door of access to Iraq from Jordan. And what does ISIL do? They put up the black flag of the Caliphate. What does this flag represent? It’s a logo, a brand, a franchising serving only to create more fear. But in reality there is the Sunni revolt against the Shia taking place. A rebellion against the supposed equilibrium that the Shia have tried to create by allying with Americans. And the Sunni think this fake equilibrium doesn’t represent them. So who is the strongest that can represent them, they say? The black flag of the Caliphate. They started allying with ISIL and this has become a very strong force. In Mosul, a few thousand ISIL fighters made a contingent of the Iraqi army of 50,000 armed men (with American military artillery) surrender. ISIL arrived, uplifted the flag and declared their state. In three hours, the Iraqi Army surrendered and escaped. In Ramadi, ISIL conquered more arms – the arms left behind by the Iraqi soldiers. Simultaneously, Shia militias are being sent there as well. War cannot be fought by two separate entities. The war of the Iraqi state is being fought by an Iraqi military that doesn’t have the courage to fight this very war. Putting Shia, armed by Iran, against Sunnis means putting two counter forces in conflict against each other. This strife will continue until one or both of these forces gives up. Sometimes war finishes because of exhaustion. When both parts deplete their forces with a mutilated population, a population that has lost all of their friends, family members and possessions. Maybe then war stops.

In the photo: Mossul, in front of the house where Uday and Qusay, the sons of Saddam Hussein, were killed. Their death signified the regime was over.

In the photo: Mossul, in front of the house where Uday and Qusay, the sons of Saddam Hussein, were killed. Their death signified the regime was over.

Q: What does war do to the human soul?

A: War takes people to the boundaries of the human soul. People can become monsters and people often kill each other for ludic reasons. I remember once I went to ex- Yugoslavia, in Vukovar the epicenter of the Serbo- Croatian war. I entered there with the Serbian army the day that the city was reopened and we found a peasant. I started talking to him and he brought me to his property and showed me a hole with several cadavers in it. He told me: “these are my neighbors. I killed them.” Astonished I asked why? and he responded: “because they were Serbian.” Although he had lived next to them happily for many years as neighbors he had killed them. Ex-Yugoslavia was a community in which Serbs, Croats and Muslims lived in harmony. When this equilibrium broke, people became capable of killing their neighbor. During war everything can change in the lives of people at a certain moment. What we considered a stable equilibrium in our lives, our sense of peace and calm in our reality is balanced on a fragile and fine line. This is what makes our peaceful way of living precious. Peace is a marvelous privilege but it’s very fragile. Human instincts are abominable. Frustration, fear and anguish make these behaviors emerge. It is an allegory to Terrence Malick’s film “The Thin Red Line.” If you cross that thin line evil emerges at any given moment.

Q: From your extensive experience in conflict zones, can philanthropy serve as an antidote to war?

Q: From your extensive experience in conflict zones, can philanthropy serve as an antidote to war?

A: Philanthropy in the sense of social justice can prevent war. The efficiency of a community is an antidote to war. When a community is well-run, war is distant. On the other hand, when a community doesn’t have a strong social fabric it is easy to instill conflict within. Trust is also very important. Being able to trust your neighbor is essential because only then a community is capable of finding common solutions to their issues. The etymology of philanthropia is empathy. When philanthropy means creating empathy in communities it can serve as a deterrent to war.

In the photo: Shia women, in south Iraq, going on their daily pilgrimage for water.

In the photo: Shia women, in south Iraq, going on their daily pilgrimage for water.

Q: A great part of your career took place in Central Asia. Why did you focus on this part of the world?

A: Because our world as we know it today was created from this very distant black hole. Central Asia was the center of the world for millennia. All of the influences and counter influences of humanity can be found there: the Buddhist, Islamic, Greek, Roman, Mongolian, Mystic and Hindu. Somehow everything ends there in the dust and disappears. Central Asia is a magical place, a place of emptiness. You can walk there for 20 hours and see only shrubs and bactrian camels – the most beautiful in the world. I first went there after reading a piece from the NY Times that told the story of Vozrozhdeniya Island located in the middle of the Aral sea and the place where Russians experimented with biological weapons (including weaponized Anthrax) on animals. After many years of this taking place, the Aral sea, once 400 km wide, has almost dried up; and Vozrozhdeniya Island, once very small, has expanded diffusing all of the chemical substances tested there all over the surrounding land. The intervention of man in nature is very dangerous when it is linked to an ideology as it can cause traumatic consequences such as this. To me this place is a metaphor to what the end of the world will look like, and I wanted to do a reportage on this preposterous no-man’s land.

Interestingly, my fixation with this part of the world became very relevant in my career. Around the time that I was doing all of my research about Anthrax and biological weapons in Central Asia, 9/11 took place. I flew to Washington D.C. 24 hours later to interview Ken Alibekovsy, the Kazak that created weaponized Anthrax and who resided there. It was a fantastic moment because he knew exactly where Anthrax came from and I had just been in the place where it was being tested. Three days later a letter with Anthrax arrived to a member of the U.S. congress. Suddenly, all of the information I had collected in Central Asia and with my interview in D.C.became very valuable.

In the photo: Kazakhstan, boats floating in the dried up Areal Sea. Dromedario in Arabia Saudita and Oman.

Q: Our world is currently oversaturated with conflict, war and negative news. Do you believe in the power of positive news and how they can serve to spark inspiration and positive change?

A: Showing with a positive story how a community has improved is very important. Chinese media, although it is not completely democratic, has a sense of community and I am impressed by that. Western media, especially Italian media has a catastrophic approach. Our media community feels that bad news equals big news. If it’s not catastrophic it sells less. Inspiring stories do not have such an effect on the audience. A journalist has to have the ability to tell a positive story but people have a fetish with negative shocking news. They are fascinated with soap opera like stories. When you use media only as a means to sell and market your product, your product needs to be catastrophic so that it sells. But information is not a type of merchandise. Information is what we understand about the world around us. It is very important that it is not sold as merchandise. If it becomes only that it loses its value.

In the photo: The first day of American military attacks in Baghdad. The view from my hotel, Il Palestinese, which was in from of the Tigris.

In the photo: The first day of American military attacks in Baghdad. The view from my hotel, Il Palestinese, which was in from of the Tigris.

Q: As an experienced journalist what do you think about the future of the media?

A: On the future of media, the speed at which news is being produced is incredible. You might begin the day with a piece of news that might be untrue because that information doesn’t have the time to be crossed-checked. If you post news in the internet by the time you have the occasion to verify the facts, this piece of news has already made it around the world a few times. The process of double-checking your sources it’s a luxury that few can afford now days. Publications post information without going through the traditional process of cross-checking. What many blogs and newspapers do now is to get information online that already exists, copy, paste, and republish. This is very dangerous because you can become a slave to propaganda and to publishing only that. Original sources of information such as the BBC, Reuters, AP, or The NY Times are becoming fewer and fewer.

Q: Behind the correspondent, who is Duilio Giammaria? What makes your clock tick every day? What are you passionate about?

A: Traveling, but only with an objective. Traveling has to be interesting; I don’t want to be merely a tourist without a purpose. I am also passionate to push my boundaries both intellectually and physically. I like to think about different ways in which both the world and human behaviors can change so we can live a better life. Gardening is also a passion of mine…and cooking. In the world in which we live now we no longer do enough activities with our hands. I like to touch things, the earth, vegetables, la pasta. I like to be hands on and to create with my hands.

In the photo: Expedition with Yaks from Wakan, in the north of Afghanistan to Chitral in Pakistan crossing the Pamir. One of the most remote places in Central Asia and one that I hold dear to my heart.

In the photo: Expedition with Yaks from Wakan, in the north of Afghanistan to Chitral in Pakistan crossing the Pamir. One of the most remote places in Central Asia and one that I hold dear to my heart.

Q: What inspires you?

A: Harmony – when there is equilibrium in the atmosphere. You can find this type of harmony even in simple situations and places. It is not linked to material wealth. My strongest inspiration is beauty, however, because to me beauty is elegant, is real- it’s not something that can be made up. You can find it inside you, in another person, inside a place. There is something magic behind it, even if people do not realize it. On the other hand, beauty can be dangerous. If you look at the Nazis, for example, they were also in search of beauty but in an perverted way. It is also interesting to see how beauty has changed over the centuries. For instance, I live in Rome – an ancient yet beautiful city – and to me beautiful things always belong to the past in a sense. I often ask myself – what is contemporary beauty? Are we being subject to a state of non-beauty in our modern world?

Q: What legacy do you want to leave behind with your work? What impact do you think you have or have had in society throughout your career?

A: The common thread in my work is not to have been too egocentric in reporting the truth. To have tried my best to make the audience feel that I wanted to help them understand an issue. Once another journalist asked me how many wars I had reported? To me this was a ridiculous question. Journalism is not a competition of numbers, it is about reporting the unbiased truth. And I have always tried to do this throughout my career.

In the photo:A girl standing inside her house which just got hit by a projectile. In her expression the strength of a little girl that war has prematurely made a woman.

In the photo:A girl standing inside her house which just got hit by a projectile. In her expression the strength of a little girl that war has prematurely made a woman.

Q: In the thousands of memories and experiences that you have collected over your interesting lifetime, do you have a most memorable one? A moment that touched you deeply?

A: My life has been so intense that I have many layers of memories. But ingrained in my mind remains the image of this little girl in Iraq inside a bombarded house. I could see her though a hole on the wall as I entered the house. She looked at me with such grace, as if she was telling me: “whatever you do I will still be here. This is my home, and I will continue living here.” As if she was saying, “tomorrow is the first day of the rest of your life.” And her profound glance touched me deeply because it made me think that life has to be lived as such, with the capacity to continue forward and to be reborn even under extreme circumstances.

Duilio Giammaria Instagram