My (Adventurous) Life at the United Nations: An Unexpected End to a Drafting Committee Session.

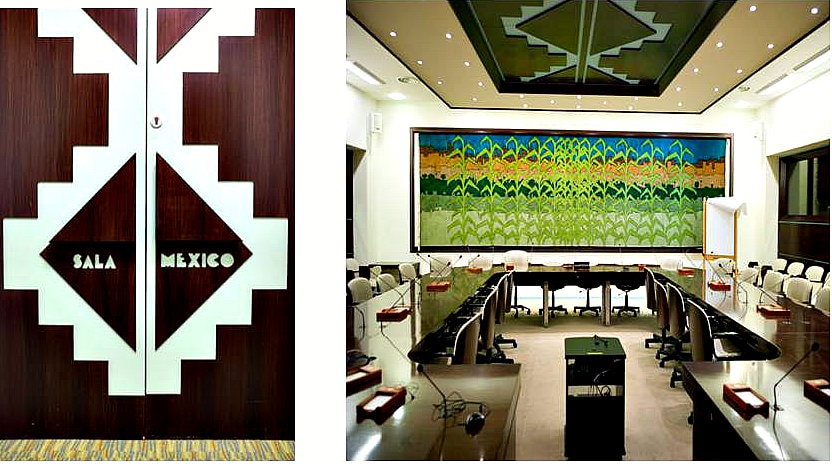

14 November 1991, 26th FAO Conference in Rome. I glance at my watch, midnight already. The delegates, thirteen in all, are sitting around the table, looking glum, staring at the papers in front of them; coming from every region, they are the result of delicate diplomatic negotiations: three each from Africa and Asia, two from Europe and Latin America, plus the United States, Australia and the Chairman from Denmark. A portly gentleman with a bold head and red cheeks, he is sitting next to me at the head of the table. Behind us, a vivid mural depicts a field of corn plants, the green stalks standing straight in a row, like soldiers at attention, and with a sun-bleached village in the background, the color of sand.

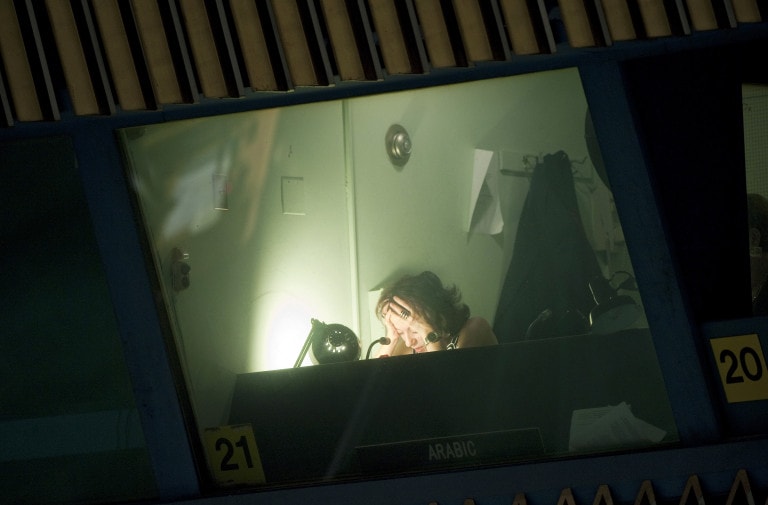

This windowless room deep inside the FAO building is known as the Mexico Room – the furnishings are a gift from Mexico – and the mural is the only focus of interest. On both sides, a string of glass panes stretch across the wall, and we can barely glimpse the blurred faces of the interpreters sitting behind them, hard at work, translating every comment made on the draft report.

The snack I had ordered for nine o’clock – only soft drinks and juices, the ham sandwiches separated from the cheese ones and clearly marked to prevent Moslem delegates from eating them by mistake – is a forgotten memory.

We started on the draft report at 7 pm, after the day’s debates were over in the main conference rooms. The draft, available in four of the official languages (English, French, Spanish and Arabic), is a mere five pages, double-spaced, only a section of the full report. I sigh, we’ve still got a full page to go before we’re done. Yet we need to finish it tonight, the report has to be adopted tomorrow – it’s the big day of the vote on FAO’s budget, the only item that is voted on at the FAO Conference, everything else is adopted by consensus.

I glance again at my watch, ostensibly, trying with that gesture to prod the delegates to move on. Because when they’re finished, we of the Secretariat still have a couple of hours of work to finalize the report for printing. I know that if all goes well, I won’t be able to get home before 3 am, driving alone in the rain, across a deserted town, taking care not to wake up my husband when I get home (but I know he will be awake and worrying). Conference work is an expensive affair for FAO; Vikram Shah, my boss, a savvy Indian who heads the budget and programming bureau, once estimated that it costs around $4 million, considering all the extra expenses that have to be incurred, from overtime pay for general staff (professionals don’t get it) to round-the-clock translating and printing of documents in all languages. For that amount of money, you could run several aid projects for thousands of needy people in the developing world.

“How is the TCP managed?” thunders the American delegate. He clears his throat and launches into a speech about the TCP a.k.a. Technical Cooperation Programme that his government would like to eliminate. But he knows that all he can get is a reduction, if he’s lucky. The TCP is a black box. Amounting to 14% of the total FAO budget – some $80 million back then – the TCP, invented in the 1980s by Saouma, the Lebanese Director General, is a special fund in the hands of the FAO’s Secretariat. The trouble with it is that it is “unprogrammed”, and country requests are filled “as needed”. Unsurprisingly, all developing countries love the TCP while developed countries, and first among them the United States, would like to know what criteria govern disbursements. Who gets what and why. And the American to conclude: “I want a sentence in there expressing our concerns. It should read: ‘Member Nations recalled their continued expectation of further measures to achieve improved understanding and transparency of TCP operations.’”

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————-Previous episode : DIARY OF A UN OFFICIAL: MISSION #1 – MAURITANIA —————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

I grab my pen and quickly jot down the American’s suggested modification. There is a moment of silence as everyone digests the importance of the suggestion.

“Where should this go?” asks the Algerian suddenly– he speaks in French because at this time, late at night and for reasons of economy, Arabic is not available.

“At the end of the paragraph concerning the TCP, of course,” says the American disdainfully.

All the delegates stare once again at the TCP paragraph. I read out the new sentence, indicating where it should be added – that is one of my tasks as Secretary to the Committee, to make sure everybody understands what we are discussing.

“I don’t think we can accept that wording,” says the Mexican, “not all countries want a change in the management of the TCP – only a minority.”

The American sighs audibly. “As I recall the debate, many Member Nations made that suggestion, it wasn’t just my country – I suggest we put in ‘many Member Nations’.”

“I disagree,” says the Egyptian, “We cannot add that sentence. I also recall the debate very well, and people uncomfortable with FAO’s management of the TCP can be counted on the fingers of one hand.”

“Four hands,” interjects the American.

The Egyptian shrugs. “Whatever. But the term ‘many’ is a clear exaggeration. I’m not going to count the numbers, I’m sure the FAO Secretariat can do this, but we all support the TCP, it’s a donor of last resort, TCP projects are small but very useful to jumpstart bigger, more important development projects and you know it.”

“I don’t know it, that is precisely my problem,” barks the American.

“If that’s the case,” says the Frenchman in French (he never speaks anything but French though his English is excellent), “we are happy to hear the TCP is so useful, but we need the evidence. We want to see the results the TCP has achieved. I am sure Egypt understands that. The sentence has to be added, it reflects the concerns of too many members to be passed up. I suggest ‘many members’.”

“No, not many,” says the Egyptian stubbornly, his thick brows knitted together. “Just a few.”

The American growls and I can hear him thinking “here we go again, a battle over a ‘few’, ‘some’, ‘several’, ‘many’…”

“How about ‘several’?” says the Frenchman in a conciliatory tone.

Both the Algerian and the Egyptian shake their heads. “A few”, they chant in unison.

“I don’t agree,” says the American. “I’m sticking by ‘many’.”

“Stop, everybody stop!” yells the delegate from Iran (in English), his tinny voice reverberating in the room. We all turn to him, astounded to hear him speak. This is the first time he opens his mouth; for the last three nights he has been a dark, enigmatic shadow at the end of the table while everyone talked. His high voice is in odd contrast to his dark full beard. But then, he is not a big man, his shoulders are narrow, his arms spindly; he wears metal-rimmed glasses and has the high forehead of an intellectual. “I can’t stand this, you are driving me mad! I cannot believe that normal, well-educated people would waste their time discussing whether to put in a sentence the words ‘many’, ‘several’ or ‘a few’.

This is ridiculous. Don’t you realize how ridiculous this is?

He stops and stares at each of us, one after the other. We all squirm uncomfortably in our chairs. I feel the man from Iran has a good point – this business about a few and many is absurd – and I’d like to smile but I don’t, I keep my face as impassive as everyone else’s.

The man from Iran leans forward. “And you Algeria, you are speaking as if you were Algeria, yet you are not a country, are you? Who said you could speak in this way? And the same goes for you, Egypt, Mexico, France, the United States. Who do you think you are? You are not your countries, you are simple persons, individuals like me!” His hand nervously rattles the table. “Grown-ups like you behaving this way, you should be ashamed of yourselves. Here we are, stuck in this room every night, and it’s been going on for three days now, and what have we achieved?”

He stops again and bangs on the table. We all jump but remain silent. “Nothing! We have achieved nothing of any value to anyone!” he screams, droplets of foam suddenly forming at the corners of his thin mouth. “This is the first time I attend an FAO Conference, you have no idea with what high hopes I came to Rome. I was really expecting to find a new world full of people of good will, concerned with the good of humanity, people genuinely wanting to improve the lot of the poor. And what do I find?”

He glares with reproach. “People who worry about grammar, people who fight over words like children, people who think they are whole countries and write reports to ‘deplore facts’, ‘express deep concern’, ‘underline the importance of this or that’, ‘reconfirm their satisfaction’…Who are you kidding with such phrases? You have a job to do, you have to fight hunger and poverty, you have to ensure growth in agriculture, this is the task of FAO. This is your task, all of you! And this is why I came to FAO and expected to see measures to improve the world where I come from. I used to teach farmers’ children in a small rural school, and I saw their poverty and suffering and I lived through their suffering too. We need to change the world of farmers…”

He splutters on the words, as if his mouth has gone dry, and stops. I suddenly feel sorry for him – an idealist who has fallen into the Drafting Committee. “Sir, are you thirsty?” I ask him. “The messenger girl can bring you a glass of water…” As I talk, the messenger girl dressed in the conservative dark blue uniform they all wear at FAO conferences, starts moving towards him, glass in hand.

He glares at me and her, furious. “Never! Don’t get near me,” he screams at the poor girl who stops in her tracks, spilling the water out of the glass. “Don’t take another step! Ever since I arrived here in Rome, there are women everywhere, on the bus, in the hotel lobby but the worst place is here, in FAO. All those young girls dressed in blue who run around the delegates, bringing pieces of paper and water and who knows what else! What kind of a place is this?”

I signal to the messenger girl to sit down behind me. Let’s see how this develops. I can feel the chairman is at a loss, he is raising his hammer, pondering whether to bang it, uncertain how to bring this to a close. He turns to Vikram Shah who is sitting on his right, the highest representative of the FAO Secretariat in the room, and he whispers in his ear.

Within seconds, the Chairman passes onto me a message written by Shah, “alert the guards”. I pass it onto the messenger girl who tries to get out of the room. “Stop!” yells the man from Iran, “nobody gets out of this room!”

The girl turns to me helpless and again I signal to her to sit down. I lean in her ear and tell her to show the message to the interpreters through the glass pane as soon as our man’s attention has moved onto something else.

When I turn to look at the man again, I can’t believe what I see. He slowly pulls out a small gun and places it in front of him. We all stare at the gun, fearing the implications. How far will this madman go? “No need to be afraid,” he chuckles, probably aware of our scared faces. “All I want from you is to adopt this report now, exactly as it is. There is no need for any further discussion, is there?”

Nobody moves. Only Shah, ever the suave Indian, finds the strength to utter the right words to assuage him. “I am certain that the gentleman from Iran should rest assured that he has made his point of view very clear to all of the delegates in this room as well as to the FAO Secretariat. Mr. Chairman, would you see any inconvenience in proceeding to close the debate and adjourn it to tomorrow?”

The chairman, speechless, nods his agreement.

“Then, our report is agreed to and we can all go home. We must thank the gentleman from Iran for this speedy conclusion,” resumes Shah, standing up and flicking the microphone shut. “I shall be happy to accompany you out of FAO,” he adds, walking around the table. The delegates are still seated, unable to move. We watch Shah shake hands with the delegate from Iran and move out of the room, his hand on the man’s shoulder.

His gun remains on the table, forgotten

Still no one moves, we all look at each other and at the gun. “I suggest we wait for Mr. Shah’s return,” says the chairman. In less than a minute, Shah is back with a guard who takes the gun away. “The guards have led him out of the FAO building” Shah tells us, “and the Iranian Embassy has been informed.”

He didn’t say anything more and we never saw that particular Iranian delegate again, either in the Drafting Committee or in any rooms of the Conference. Needless to say, the sentence criticizing the TCP was adopted with the phrase ‘a few Member Nations recalled their expectations of further measures to improve transparency…’