To control the COVID-19 pandemic, will a vaccine be enough? This article makes the case that more than a vaccine (or several vaccines) is needed and that bringing together the two major existing health systems that are now separate, one for Animals and another for Humans, would produce a greater synergy. A synergy that would go a long way to help control the coronavirus as well as future pandemics. In short, the One Health approach works better because it pulls together human and animal health systems.

November 9, 2020, brought the world the amazing and wonderful news that a COVID-19 vaccine produced by Pfizer/BioNTech had proved 90% effective and that the companies would move forward along the pathway to approval, application, and ultimately widespread distribution.

This particular vaccine is based on a novel technology that uses synthetic mRNA to activate the immune system against the virus. Two separate doses are required, roughly one-month apart, and the vaccine must be kept at minus 70 degrees Celsius (-94 F) or below. This is much colder than most freezers can provide. “The cold chain is going to be one of the most challenging aspects of the delivery of this vaccination,” said Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

Once widely available, the super-cold storage requirements will prove to be serious obstacles even for the most sophisticated systems and informed populations, and more so in rural areas or poor countries where infrastructure and resources are tight. So don’t expect the vaccine to become widely available anytime soon.

To be sure there are many other COVID-19 vaccine versions under development with some, such as Moderna and Johnson & Johnson, looking promising (Moderna’s vaccine also requires cold storage but within reach of most widely available freezers). In the near future, it is highly likely there will be more than one vaccine, and some may not require super-cold storage, or even modest or any cold chain handling, or require only a single dosage.

Whatever emerges as to how this pandemic is dealt with, vaccines are only the tip of the iceberg. To understand why, it is worth looking more deeply into the human-animal health links, and explore where there is potential common ground for the fruitful development of more effective therapies.

In terms of context and science, in many low and middle-income countries (LMICs), livestock is the income-earner and considered the productive sector and therefore has attracted investment, with the poultry or livestock sector having better infrastructure in rural areas than the human equivalent.

Attention to veterinary medicine is often seen as affecting the family and community income basis, which becomes a priority for the individuals. However, this is not necessarily so for the pharmaceutical industry focused disproportionately on research, product development, and promotion of therapies focused on human health.

There have been valuable instances of crossovers between medicines first developed for animals which then have a crucial use for humans and vice versa. One such recent case was Ivermectin, a product Merck initially designed for livestock. Once its potential human benefit was understood, it contributed enormously to the (near) elimination of River Blindness in West Africa that had been a major public health problem, affecting local economies.

Better control of River Blindness opened up the Senegal River Valley and other affected areas in Africa and across the world to both people and agriculture. While it will take an estimated 30-40 years to fully eliminate the disease, Ivermectin is still a big step forward to control diseases for which there is, at present, no vaccine.

The practice of human immunization from animal infection has animal linkages from its earliest days. Buddhist monks drank snake venom to confer immunity to snakebite; the smearing of a skin tear with cowpox to confer immunity to smallpox was practiced in 17th century China. Edward Jenner, the founder of vaccinology in the West in 1796, inoculated a 13 year-old-boy with cowpox to demonstrate immunity to smallpox. In 1798, the first smallpox vaccine was developed. Over the 18th and 19th centuries, systematic implementation of mass smallpox immunization culminated in its global eradication in 1979: Total elimination took almost precisely two hundred years.

Today we know that vaccines are crucial in the control of many human and veterinary diseases. Routine vaccination is used by most countries to control about 15–20 human infectious diseases, and roughly another 15 diseases are selectively targeted. Compare that to veterinary medicine where it is estimated that vaccines are available for over 400 diseases affecting mammals, birds, and fish, including farm animals, pets, and wildlife.

That said, revenues from the global human vaccine market are over 30 times that of veterinary vaccines. The higher cost of human vaccines can be traced (partly) to the fact that evaluation of vaccine effectiveness (which is expensive and time-consuming) is largely limited to human vaccines while animal vaccines are merely evaluated on efficacy, causing a difference in evaluation methodologies that will need to be overcome.

Finally, there is another aspect that indirectly reflects an important difference: academic time devoted to parasitology is significantly more in schools of veterinary medicine than in human medical schools.

Obstacles to Vaccines Performance

The performance of both human and veterinary vaccines “on-the-ground” varies and is not always predictable. Sufficient epidemiological data must have been accumulated from the start and carefully evaluated before even reaching the point of application.

The challenges and pitfalls are many, including differences in the potency of any vaccine batch; poor administration from procurement to supply chain management; failures to observe shelf-life and where necessary, cold chain requirements; factors such as the nature of the pathogen, especially with new and novel strains; and environmental factors that influence immune response, such as genetics and nutrition.

In short, population density and nature, and frequency of contacts will all affect results, as will the reliability of power, water, and sanitation.

One of the greatest obstacles is weak/insufficient outreach capacity. In Africa, but also in other parts of the world with similar conditions, vaccination services for people and livestock often fail to achieve sufficient coverage in remote rural settings because of financial, logistic, and service delivery constraints.

Benefits from Veterinary and Human Health Systems Working Together

A notable example comes from Chad. There was an effort from 2000 through 2005 to demonstrate the feasibility of combining vaccination programs for both nomadic pastoralists and their livestock. It was found that sharing transport logistics and equipment between physicians and veterinarians reduced total costs.

Joint delivery of human and animal health services was adapted to and highly valued by hard-to-reach pastoralists. The results were remarkable. 10% of nomadic children less than one year of age were fully immunized annually and more children and women were vaccinated per day during joint vaccination rounds than during vaccination of persons only and not their livestock.

The experiment conclusively showed that by optimizing the use of limited logistical and human resources, both public health and veterinary services become more effective, especially at the district level. This is one example of how the synergies of the two disciplines can benefit both.

Another perspective is the regional experience and response in West Africa in the face of Ebola.

Some eleven countries were on the frontline of the Ebola outbreak from 2014-2016. They learned from that experience of the need to improve pandemic preparedness and as a result, they subsequently embarked on major sub-regional disease surveillance system enhancement projects that encompass both human and animal disciplines, policies, and planning.

Expect these countries to have a leg up as they benefit from having had their human medical and veterinary medical professionals brought together before the coronavirus hit, making them better positioned to deliver a COVID-19 vaccine whenever one is determined as safe and effective.

COVID-19 is not the first pandemic nor will it, unfortunately, be the last.

What is needed going forward is a greater acknowledgment of the relationships between animals and humans beginning with professional education, the systematic pursuit of synergies in research as well as on-the-ground applications, whether in early surveillance, diagnosis, and utilization of the differing infrastructure and facilities such as cold storage systems.

In short, we need a paradigm shift to a One Health approach. To paraphrase and expand upon the famous 1871 Lewis Carroll novel quote in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland/Through the Looking-Glass: “The time has come,” the Walrus said, “to talk of many things…” We must implement post-haste, this One Health approach, applying it as a priority to research that is critical to save and protect planetary life.

During the early 21st century, particularly throughout the past decade, numerous leading national and international global health-oriented individuals, groups, organizations, and governmental bodies have expressed strong support for interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary utilization for public health and clinical health advancement, i.e. the One Health concept—now some would say before it is too late. Unfortunately, this support has not yet translated into widespread adoption.

The world was unprepared to deal with the current tragic coronavirus pandemic, a virus already dangerously mutating, as we know, in Denmark with minks transferring a new form to humans.

Simply put, we need a universally employed One Health approach in place now so we can more effectively deal with future health challenges, ones we will surely face, possibly next year or the next decade, whenever.

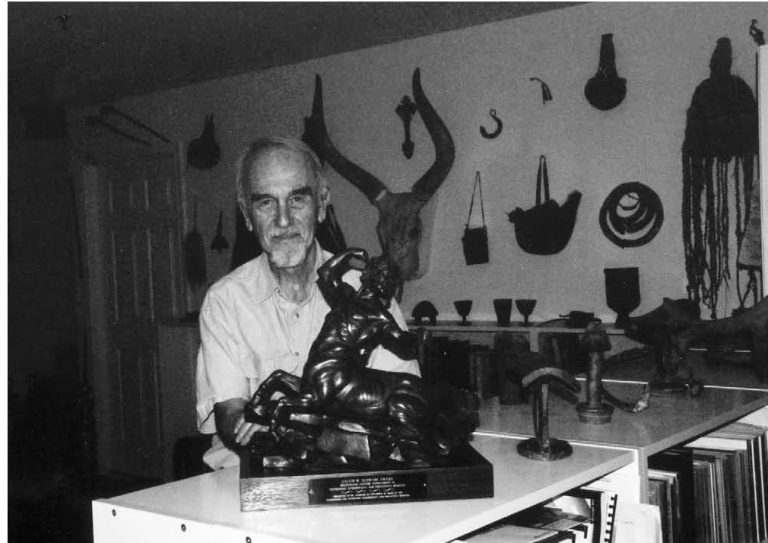

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Featured Image: UF Research. The Sex Differences Group will analyze the differences between men and women in regards to COVID-19 disease severity and death Source: Screengrab from video, One Health Center of Excellence at the University of Florida (UF).