The subject of “Civility” dealt with in a recent Impakter article has generated a wide range of reactions, some believing we cannot abandon civil discourse however difficult it may be to change radical behavior, while others holding it infeasible any return to common civility to address our differences.

Whichever view you may hold, it is worthwhile taking into account what we can glean from history, as well as wider implications for global survival if we continue failing to address wide gaps in poverty and social inequality, the environment, including linkages between it and human and animal wellbeing.

First for the broader view and how “civility” writ large, touches on our common global future, as put forward by Professor Ulrich Laaser of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Bielefeld University:

“Enhancing civility is mandatory, no question! But the real question is rather: how to enhance civility? Is it sufficient getting citizens to adopt a convention on decent behavior? It seems that in most if not all societies there is a potential for indecent behavior only waiting for an opportunity to exercise aggressive communication and even physical attack. This potential may be smaller in more equal societies (Scandinavia?), but it will be unlocked by steepening social gradients or, for example, by a pandemic like COVID-19 and the restrictions coming with it.

The German history of the last 150 years is a good example of unlocked aggression. Starting from Kaiser Wilhelm II’s immature personality but almost absolute power on last decisions, to the unbalanced Treaty of Versailles, and the financial crash of 1929, the stage was set for extremist groupings to take over. Today, the largely uncontrolled social media make it even easier to form extremist cocoons growing fast in times of general hardship when people look desperately for an exit.”

Neil MacGregor, former director of the British Museum and since 2015 first director of the Humboldt-Forum on art and history (the remake of the huge Prussian castle in central Berlin) writes in his recent book “Germany. Memories of a Nation” (ed. note: This is a translation of the text on p.154 of the German edition, using Google):

“More than any other object in this history of Germany, the Buchenwald Gate, which was built practically within sight of Weimar and everything that this city stands for, leads us back to the unanswered, perhaps unanswerable question of how this could have happened. Why have the great, humanizing traditions of German history – Duerer, Lutherbibel, Bach, the Enlightenment, Goethe’s Faust, the Bauhaus, and very, very many more – been unable to prevent this total moral collapse, which led to millions of murders and a national catastrophe? These are the questions that every German has to grapple with today. The gate and the man who designed it dismiss us with one more question: What would we have done?”

Professor Laaser added an explanatory note regarding “the gate and the man who designed it”: MacGregor refers here to Franz Ehrlich, a Bauhaus architect, a prisoner in Buchenwald (he worked there as an “indentured” laborer) and tasked to design the writing on the inside of the gate: “Jedem das Seine” – to each what they are due – from the ancient Roman “Suum Cuique” turning its original meaning around.

Then Professor Laaser added a pertinent observation: “We see today large sections of our societies as well as in a global dimension being deprived of a decent living – e.g., in the big cities, in the former GDR, in England, and especially in the US, not to mention the global South – how can we expect that they behave decently!”

And he concluded his reflection, noting that the Impakter Civility article states: “If the behavior in the pandemic is a function of mutable group processes rather than fixed tendencies, then behavioral change is possible.” This, he says, is exactly the question: “if”. And he adds:

“And the same conditional factor bears on the interface of environmental/animal/human health and wellbeing, which is the “One Health” concept: If we do not get better at equalizing social gradients (even vaccines are unequally distributed), a huge reservoir of non-civility will remain.”

It is important to note that in recent times Germany, under leaders such as Angela Merkel, has shown compassionate leadership and commitment to democratic principles far better than most.

Contrast Professor Laaser’s position with those who think we have crossed the Rubicon, that we have reached a point well beyond civility, certainly in the United States.

This latter view was succinctly put to me by an author who emailed his comments but wishes to remain anonymous; he is a staunch liberal and fears democracy is doomed unless good people rise up and confront those pressing to destroy basic principles of human decency:

“I totally disagree (with any prospects for civil dialogue). What you’re suggesting is appeasement. Being civil to Trumpies is playing right into their hands. What a lot of liberals and moderates seem not to realize is the depth of the crisis we’re in.

Although the meaning of “civil” is different, I fear civility as recommended [in the article] will do nothing to head off and might rather exacerbate the likelihood of a modern-day Civil War (though nothing like that between the North and South of the 1860s, more like terrorism and violent protests).”

Then he concluded with a pointed question: “Finally, to whom exactly are you recommending adoption of a civil tone? Can you imagine the impact in recommending that the Third Reich and the slaveholding South be more civil? Rather, we need to do everything we can to crush the righties at the polls, even if we have to adopt some of their tactics.”

He later explained that he was not arguing for physical violence, but hateful words can be just as dangerous as guns in inciting violence and civil unrest as was the case in the United States and the January 6th assault on the Capitol. These must be countered with very strong words and appropriate actions, albeit non-physically violent ones.

There is, of course, truth in what is said in both cases. The underlying question for all of us is whether there is any way forward?

We cannot reduce political polarization without civility. Though not sufficient, it is necessary for the existence of a democratic polity. The moderates and those in a position to take action need to find ways to appeal effectively on cultural grounds, as well as economic grounds, to disaffected people living with inequality and poverty and improve their circumstances.

This is a very difficult task, but an essential one. And certainly, it may be impossible to win over the most violence-prone people in any society, rich or poor, developed or developing. But one small but necessary step may be in treating the middle ground of non-violent disaffected people with civility and respect. Not a satisfying answer to the behavioral “if” question, to be sure, but what more do we have?

Professor Laaser was consulted and contributed to this article.

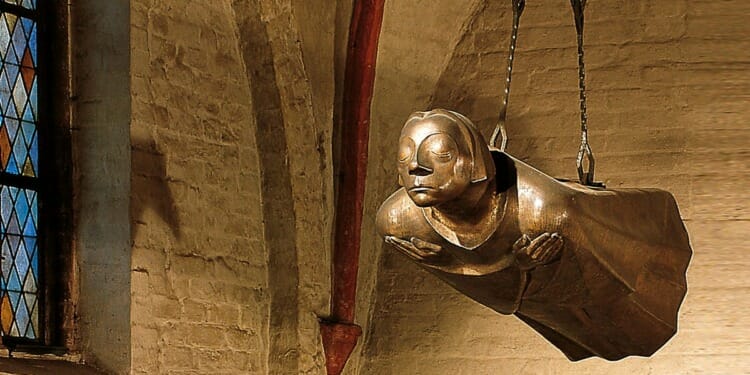

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists and contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Ernst Barlach’s sculpture Hovering Angel, a unique World War I memorial, commissioned in 1926 to hang in the cathedral in Güstrow and melted down by the Nazis who disliked it – it was remade from the original cast; Neil Mc Gregor talks about it on the BBC (here)