The 2019 coronavirus has now expanded from China to over 25 countries, killing more than 900 people () and infecting over 39,000 ( as of 10.02.2020) – far worse than SARS (Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome, a lethal pneumonia-like virus) seventeen years ago. Wuhan, a central China town that is the virus’s epicenter has expanded quarantine, covering all its 11 million people, as much as New York City. The hope is to contain the virus there though it is too soon to know whether the quarantine is working. The outbreak is worsening as the World Health Organization expressed concern over contagion of people who have never traveled to China. A cruise ship in Japan reported 66 more infections, taking the spread of coronavirus outside China to 136.

Markets are shaken, the IMF chief has just issued a warning that global growth is threatened. China accounts for approximately one-third of global growth, as Andy Rothman, an economist at Matthews Asia, an investment fund manager, recently noted.

Factories in China are temporarily closed or slowed down. Global supply chains could be disrupted. Chinese authorities have just announced they would inject liquidity in the economy, including $22 billion in the money markets and other measures to sustain the financial markets.

Nobody knows whether that will be enough. Nor how long the coronavirus outbreak will last or how many lives it will ultimately claim. We only know that it will surpass SARS by a long shot. This is a pandemic that will last through the Spring and cause economic and social disaster probably near or more than $1 trillion.

The 2019-nCov virus could very well become another UN Security Council item. It has done so for HIV/AIDS, SARS and for the third time in August 2019, the UN Security Council addressed Ebola, reiterating its grave concern over the most recent outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, highlighting the urgent need to respond since the disease could spread rapidly, possibly with serious humanitarian consequences and impacting regional stability.

What’s different this time is that this virus is affecting the world’s two largest global economies and superpowers. The U.S. requested the World Health Organization (WHO) to “engage directly” with Taiwan in the fight against the coronavirus on February 6, prompting a swift rebuke from the Chinese delegate, reminding the U.S that Taiwan is not a member of the WHO. This political dimension is likely to spread to other international organizations, engaging them further in the fight to control the outbreak.

Coronavirus transmission is occurring human-to-human even by asymptomatic carriers and it began much earlier than the Chinese initially indicated. WHO was late in declaring it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, but since the Chinese were doing more than any country had done before in seeking to isolate it, it’s partly understandable.

The Health Risk of the 2019 nCoV Coronavirus Compared to Flu and Measles

To put this new coronavirus in perspective, consider two common (and recurrent) epidemics, flu and measles. The situation in the US provides an example of the substantial burden such epidemics can place on people. According to CDC estimates, “influenza has resulted in between 9 million – 45 million illnesses, between 140,000 – 810,000 hospitalizations and between 12,000 – 61,000 deaths annually since 2010.”

As to measles, the problem is that when people refuse to be vaccinated as is now occurring in the United States, it can cause immune amnesia, especially in the young. Immune amnesia is an impairment in the body’s immune memory. By protecting against measles infection, the vaccine prevents the body from losing or “forgetting” its immune memory and preserves its resistance to other infections.

Flu and measles may sound worse, but the difference is we don’t know enough about this new coronavirus, how damaging it can be in terms of morbidity, and what vaccine and medicine options there are.

How it Happened: The Consequence of Ignoring Zoonotic Diseases

Cheryl Stroud, Executive Director of the One Health Commission wrote pointedly asking:

“How many infectious diseases that pass between humans and animals does it take for us to understand how connected human health is to animals and our shared environment, and to take needed actions?”

Indeed. As she reminds us, the list of zoonotic diseases is long and most have occurred in our lifetime, among them: HIV/AIDS originating from the consumption of wild animals in Western Africa; West Nile virus, a ‘vector-borne’ disease transmitted by mosquitoes; SARS originally passed from bats; Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome virus (MERS) from camels; Ebola from bats; Zika another vector-borne disease transmitted by mosquitoes. As she says, “so now it’s coronavirus, possibly originating from a live animal market or other route in China.”

Doing nothing is costing far more than we realize.

For example, a 2018 Journal of Infectious Diseases article hugely expanded the costs of the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak from an initial range of $2.8 – $32.6 billion to as much as $53 billion. The SARS epidemic in 2003, which spread to 29 countries, cost between US$30-50 billion; MERS, when it reached South Korea in 2015 caused $700 million in losses.

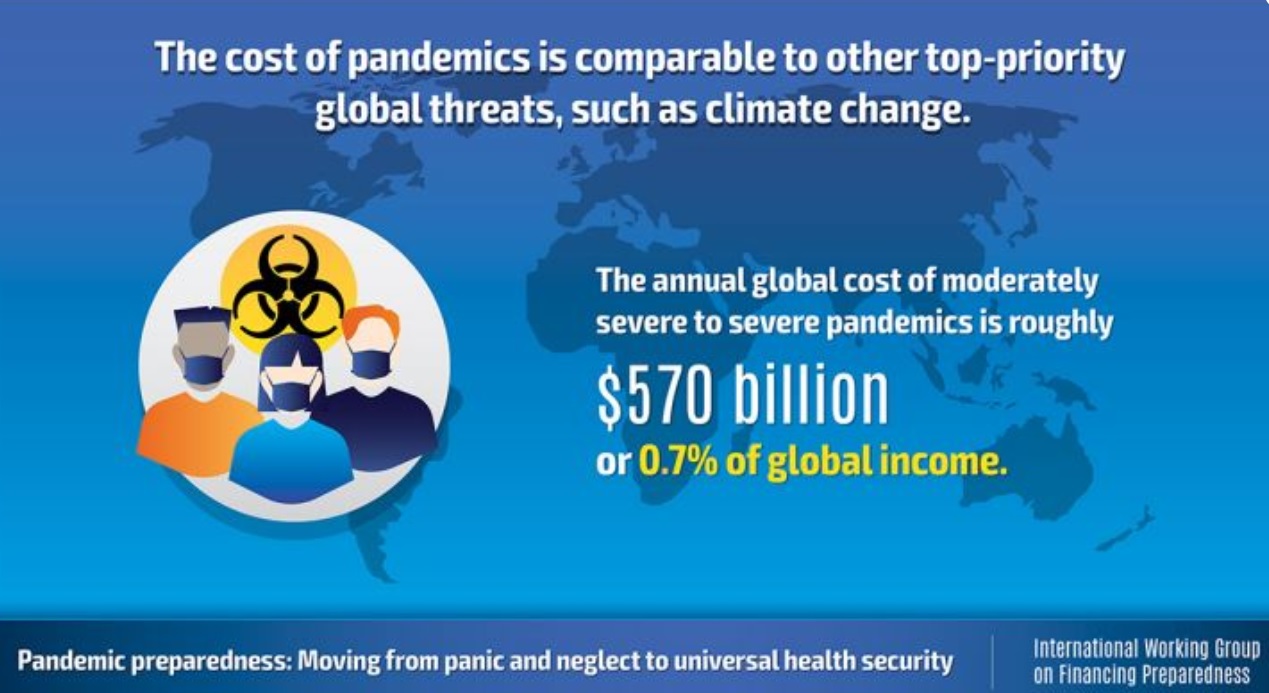

A World Bank Group paper presented to the World Economic Forum attempting to assess the economic damage of outbreaks concludes:

“All told, the annual global cost of moderately severe to severe pandemics is roughly $570 billion, or 0.7% of global income – a cost in the same order of magnitude as climate change. And, remarkably, estimates suggest that only 39% of the economic losses from outbreaks are associated with direct effects on infected individuals. Rather, the bulk of the costs results from healthy people’s change of behavior as they seek to avoid infection, representing ample opportunity for mitigation.”

It’s not a question of “If” but “When” and “Where” another infectious outbreak will happen, one that will be termed by WHO a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. We were surprised by West Africa Ebola, MERS, Zika, but we can be certain there is another one lurking out there.

Viruses know no walls, borders, or separation by oceans. For Africa where many of the past pandemics have originated or have been disasters, It is a matter of “pay for it now, or pay much more later”.

The Solution: A One Health Approach

When we speak of “health” we usually mean “human health”. But over 70% of infectious diseases affecting “humans” are zoonotic, from animals to humans. For optimal health outcomes, we need to take into consideration human, animal, plant, and environmental health. That integrated strategy is at the heart of the “One Health” approach.

Things, fortunately, are beginning to move in the right direction. From Thailand and Viet Nam to Nigeria and Colombia, countries are embracing One Health linkages and implementing One Health at the government level for their own self-preservation. Progress is especially perceptible in Africa:

- a new African Center for Disease Control and Prevention, an initiative of the African Union, is making major investments in many of its 55 member countries;

- this includes linking human and animal health at the laboratory level: Biological Safety Level 3 laboratories (BSL-3 laboratory) in Zambia will be shaped like a horseshoe: one side for human virus analysis, the other for animal virus analysis, and the center for joint conferencing and administration.

- One Health is included in African development programs, notably the World Bank’s REDISSE Pandemic Preparedness Program, a $660 million program covering most of West Africa.

In the US, there is also greater attention to One Health. In particular, in the Senate, there was a bipartisan resolution introduced by Senators Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) and Martha McSally (R-Ariz.) making “January 2020 One Health Awareness Month” and Congressional bills have been introduced to create a national One Health framework and annual reporting.

The United States Agency for International Development, the major American aid agency, is moving forward and is taking up One Health capacity building. This is encouraging, considering that earlier it had abandoned the Global Virome Project, a ten year, $3.2 billion effort to create a global atlas of pathogens that threaten or might threaten humanity. The Chinese, Thais, and others are going forward with the GlobalVirome project.

However, much more needs to be done.

There is a clear need for more public sector research support for new antibiotics or alternatives, vaccines and treatments.

Finally, it is a matter of raising public awareness of the danger. The One Health Commission is actively developing programs for One Health education and awareness from grade school level to university and beyond in communities and civil society through One Health for One Planet Education (1HOPE) campaign.

The 2019 nCoV outbreak is a wake-up call to communities, governments international institutions and development organizations to place our “One Health” high on the action agenda.

Featured image: Pictures uploaded to social media on January 25, 2020, by the Central Hospital of Wuhan show medical staff attending to patients, in Wuhan, China. THE CENTRAL HOSPITAL OF WUHAN VIA WEIBO /via REUTERS