Feminism is a radical and forward-looking movement, which has a global reach with the aim to trigger the liberation of women and society based on equality for all its members. Naturally, the movement seeks to question, protest, and overturn male supremacy for creating a world-changing phenomenon of parity.

In the interest of achieving the avant-garde goal, contemporary feminism faces the special challenge of establishing its usefulness not simply as an academic program, but also as a tradition and as a force to connect socio-political and cultural fields with the academic pursuit.

One of the reasons for the movement’s requirement of robustness lies in the fact that its revolutionary nature ultimately exposes the status quo, which is why it indirectly threatens the groups that benefit from existing conditions.

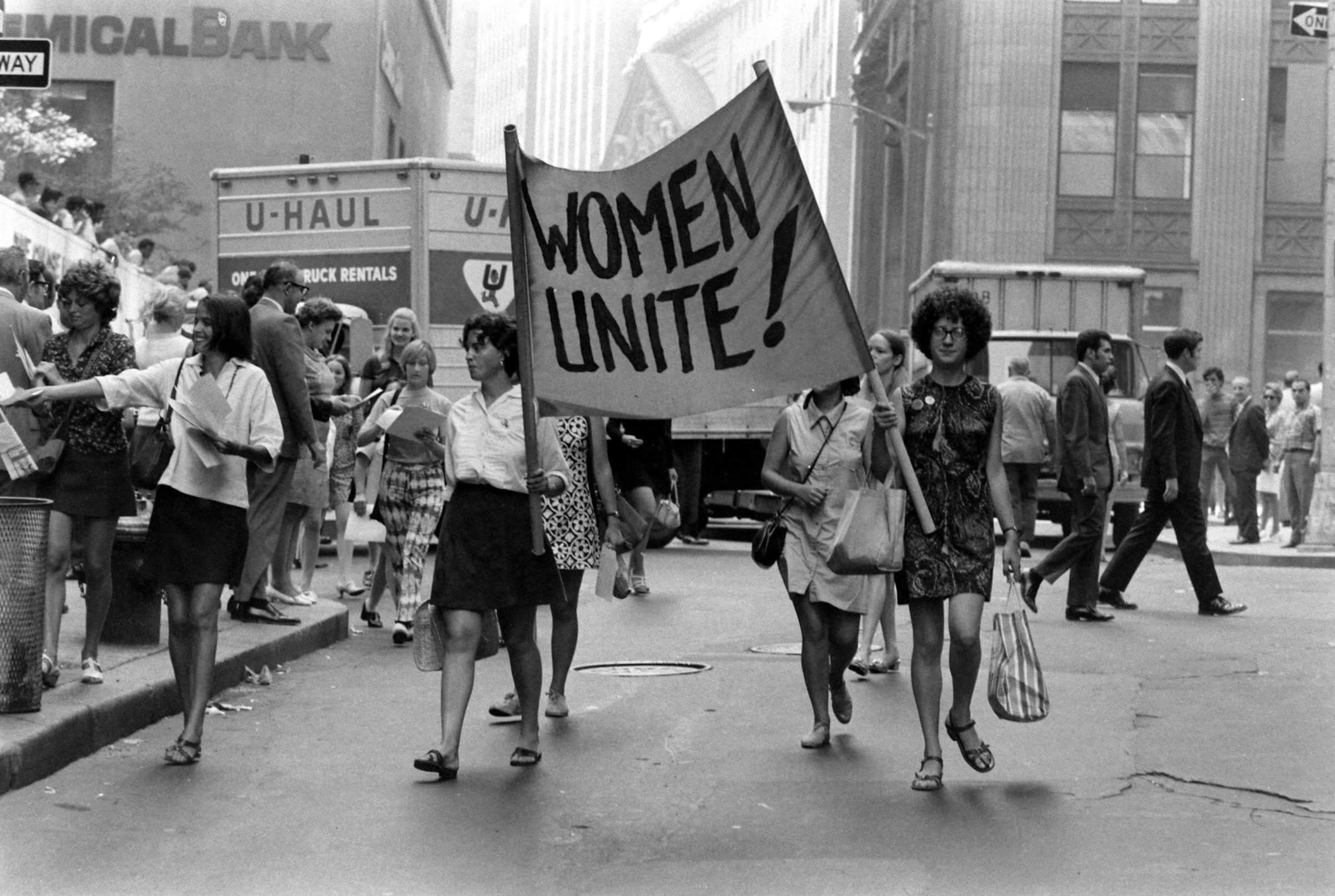

Therefore, contemporary feminists have to be aware that the movement will be a perpetual struggle, which has to be fuelled by the knowledge that inspired the women who pioneered the movement.

These women who paved the way for current feminists enabling them to take the spotlight today took their strength from the belief that positive societal change for gender equity was inevitable.

Surely that is true: Change is required for creating a sustainable future for both men and women. After all, feminists cannot aspire for equality with men, who also suffer from inequities like classism, racism, and economic deprivation.

Faced with social injustices, men usually have recourse to masculinist control over women. As a result, wishing for equality with men under the status quo is completely undesirable for the womenfolk. And clearly, challenging misogyny becomes a foremost duty for feminists in contemporary times. Ultimately, the aim is to restore faith in the individuality, potential, and humanity of both men and women.

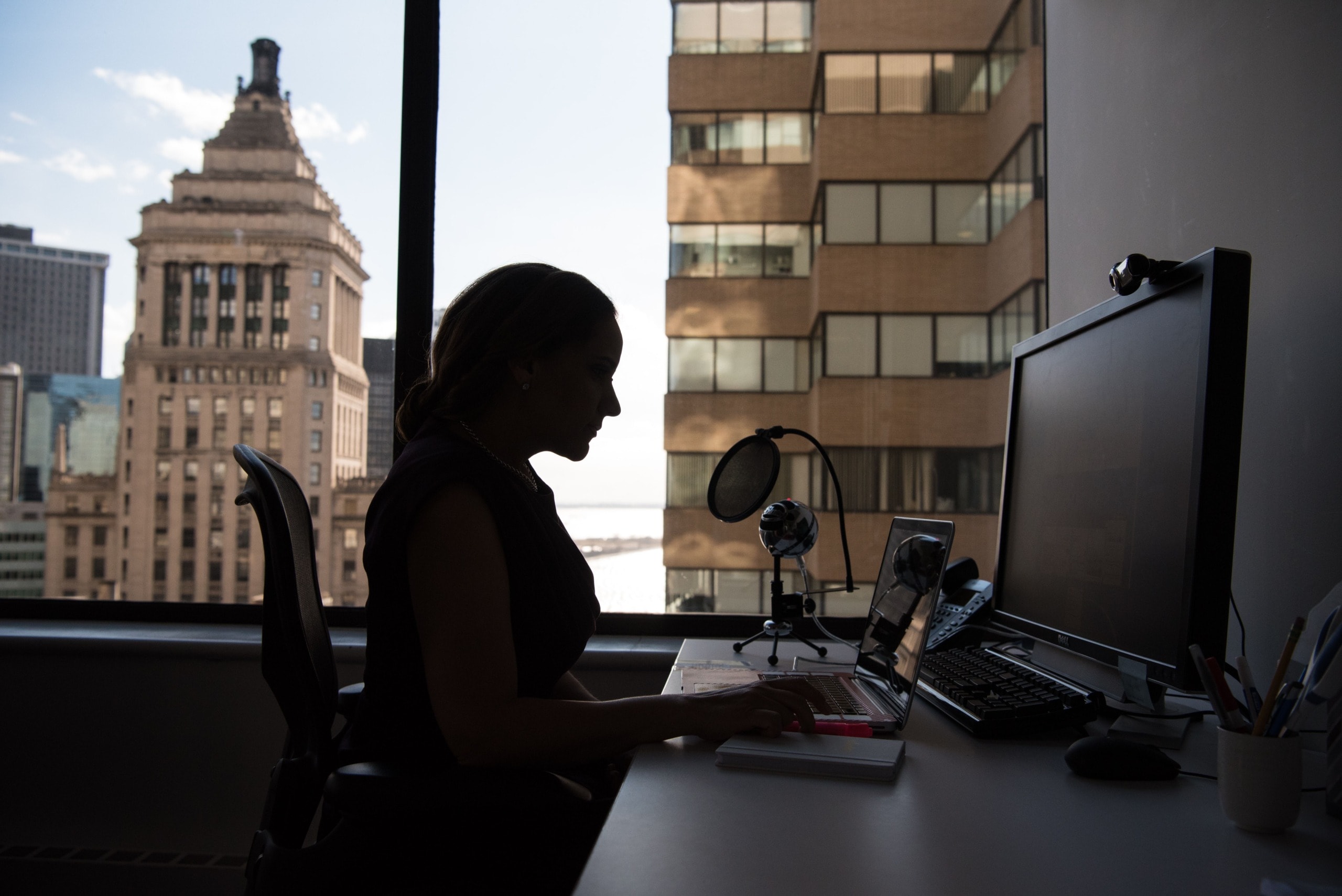

Contemporary Feminism in the digital world: The role of Cyberfeminism

One of the visible aspects of contemporary feminism is Cyberfeminism, a term coined in the early 1990s to describe feminist activities on the Internet. It serves activists by providing them with various websites that offer substantial advice, reading materials, action networks and events, merchandise, and platforms for building communities and connections.

Thus, the digital world appears as a sort of ‘home’ for connecting women across several arenas including those of work, education, and civic engagements. However, this technological experimentation can have both positive and negative influences on women’s lives, as a result of either resisting or reinforcing hierarchies of gender, race, and class.

While the complexity of the cyber ‘home’ is unavoidable, its poignant role in bridging the generational gaps between conventional and contemporary feminist movements is indisputable.

Cyberfeminism helps today’s feminists to reconceptualise their generational dynamics. When older feminists have the opportunity to share their historical and philosophical visions with the younger feminists, the latter can assure the former of their effective utilization of their intellectual and organizational inheritances.

Most of the time, the exchanges reveal that the main challenge for contemporary feminism is to create a diverse and inclusive environment by not only addressing women’s lives in the way the feminist organizations and agencies attempted to do during the 1970s and 1980s but also through being accommodative of the fact that today’s feminists are situated in a very dissimilar context than that of the earlier feminists.

Therefore, being responsive to changing societal patterns that impact the lives of contemporary women is incumbent on them through their beliefs and actions.

Some notable feminist responses to the new context arising from changing societal patterns – from America, Europe and India

Scholars of the American women’s movement have had the leading role in illustrating how contemporary feminists add a multitude of meanings, traditions, and identities to feminist activism. Among them, N. Katherine Hayles and Donna Haraway are perhaps the most notable theorists.

A professor at Duke University, Katherine Hayles is a post-modern literary critic, best known for her bestseller, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics (published by University of Chicago Press, 1999).

In it, Hayles makes the case that cybernetics equates human-ness with disembodied information and that this is just “another male trick to feminists tired of the devaluation of women’s bodily labor”, as one critic said when reviewing Hayles’ book. Another critic saw her book as a challenge to the general assumption that the human body is white, male and European, though perhaps not an effective one, as it leaves some questions open about “which interventions promise the best directions to take.”

Donna Haraway has had a long career in academic, scientific, and activist work that brings together biology, culture, and politics. As a Distinguished Professor Emerita in the History of Consciousness Department at the University of California Santa Cruz, Haraway enjoys expertise in science and technology studies, feminist theory, and multispecies studies.

In 2002, she was awarded the John Desmond Bernal Prize, the highest honour given by the Society for Social Studies of Science, for “illustrious contributions to the field over the course of the awardees’ careers”. Haraway’s most famous text remains “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century”, a long essay published in 1985 in the Socialist Review (a U.S. journal that ended its publication in 2002). The essay was later included in Manifestly Haraway published by U. of Minnesota Press, 2016.

In this essay, Haraway offers “an oracular meditation on how cybernetics and digitization had changed what it meant to be male or female – or, really, any kind of person,” writes one critic as an introduction to her interview with the scholar.

Other critics question the radical politics of the essay due to the still-not-fully-discovered effects of “organico-machinic integration” but insist that the writing inspires feminists to utilise technologies to challenge “the pernicious notion, popular at the time [of the essay’s publication], that women belonged exclusively to ‘nature.’”

However, Europe did not stay behind and it also had some remarkable theorists, among them Susanna Paasonen and Sadie Plant. And we should not forget to include in this remarkable array Radhika Gajjala, born in Mumbai, India, and a Fullbright scholar.

Susanna Paasonen is a Professor of Media Studies at the University of Turku, Finland. As a feminist scholar, she writes about internet research, affect inquiry, and sexuality studies. This inquiry broadens the scope of not only media history but also materiality and pornography. Her most popular book is Dependent, Distracted, Bored: Affective Formations in Networked Media (published by MIT Press, 2021).

This was the product of a decade-long project that challenges the zeitgeist narratives regarding social media addiction by demonstrating how its various platforms like mindfulness apps, click baits, self-help resources, and so on “entice users to alleviate boredom through online engagement,” as two critics stress while discussing data-governed capitalism.

Another critic looks into Finnish politicians’ ambivalent dependence on social media through the lens provided by Paasonen’s book to conclude that “[i]nstead of evaluating social media according to what it does to us, it is fruitful to analyse the porous boundary between the subject (user) and the object (platform).”

In the above video, Professor Susanna Paasonen participates in the event organized on 26 April 2022 by the Sidney Social Sciences and Humanities Advanced Research Center – focused on the question: Why is Sex Objectionable

Sadie Plant is a British philosopher, cultural theorist, novelist, and poet. Her research on the socio-political impacts of cyber-technology profoundly influenced the development of cyberfeminism.

Her seminal book, Zeros and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (published by Fourth Estate, 1998), argues that women’s multitasking role enters into a new phase after the shattering of “the steady, focused forms of the traditional male-dominated workplace” by information technology, since the multi-talented womenfolk can finally emerge as the crucial workforce “in a world where the boundaries between nature and artifice are dissolving into an ocean of fragmented possibility,” as a critic underlines the major contribution of the book.

Another critic defends the book, pointing out that it is not simply cyberfeminist bluster as it highlights that the internet simultaneously connects the grass-roots people everywhere, and reveals that “the current forces of control— social, political and religious— are just as strong, if not stronger,” which is why human beings need to be wary of the changing times.

Radhika Gajjala is a Professor of Media and Communication and of American Culture Studies at Bowling Green State University, U.S., whose research interests include globalization, digital labour, feminism and social justice. Her genre-defying book, Cyber Selves: Feminist Ethnographies of South Asian Women (published by Altamira Press, 2004), offers a Global-South critique of cyberfeminism.

As a critic asserts: “Part manifesto, part ethnographic study, part dialogue, Cyber Selves provides a provocative look at Radhika Gajjala’s attempt to form cyberfeminist electronic spaces for a variety of audiences, including South Asian women, academics, and writers.”

Another critic points out that Gajjala’s politics lies in delineating how cyberspace enables the diasporic women’s participation in public space, which is usually denied to them, though the writer questions “if the Internet can, indeed, empower underprivileged individuals and communities to improve their lives in material and emotional terms.”

My assessment of Cyberfeminism based on writings like the above tells me that online activism only matters if it also translates into offline results of improving women’s lives in a positive way.

One of the objectives of Cyberfeminism, then, is to participate in the rich online ambiance and transform it into collective action in the actual world.

For this, the activists have to be mindful of the fact that they have to examine how social change initiatives and locations are shifting and how the outcomes can be measured, understood, and analysed.

This leads us to one of the most important ideas of contemporary feminism: Intersectionality.

The next step forward for feminists: Intersectionality

Intersectional theory is the recognition that we all have interwoven and heterogeneous aspects of identity that determine the ways in which we perceive power and oppression.

How to apply a feminist lens to the spectrum of multiple identities in order to fully understand the patterns of dominance affecting women becomes the key point of everyday activism regarding the inclusion of the female members of a society in its cultural processes.

For example, contemporary feminists need to look closely at Western women’s feminism and organizations to see what barriers exist to racial and ethnic diversification.

Black feminist scholars have noted how feminism championed by women of colour has not always resonated with feminism introduced by White women. Most notable among them are Bell Hooks, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Angela Davis, and Patricia Hill Collins.

Bell Hooks (aka bell hooks, in lower case) who died in 2021 at the age of 69, was a Distinguished Professor in Residence at Berea College, who became a revolutionary cultural theorist and activist, public intellectual and prolific writer. Hooks wrote about 40 books in her more than four decades-long career.

Scrutinizing the intersecting oppressions of gender, race and class, her writings additionally brought into focus her concerns with issues related to art, history, psychology, sexuality, and spirituality, ultimately placing love at the heart of regenerating human beings through storytelling.

Hook’s outstanding legacy is reflected by her classic text, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (published by South End Press, 1981, and Pluto Press, 1987), which examined historical racism and sexism, by presenting the treatment of the Black female slaves as a context to the injustices experienced by the contemporary women belonging to the race.

As one critic illustrates, Hooks examines in this text “why so many white women joined the abolitionist movement, and what the growing influence of racism in the suffragist movement revealed about its class basis.”

Another critic infers that this is a groundbreaking book also for not advocating “a separate black women’s movement,” because the visionary writer was able to realize this to be “counterproductive to the greater power a well-organized collective women’s movement can have.”

Proper knowledge about these cultural and racial variations in what it means to be and do feminism can add enormous value to contemporary women’s movements.

In addition, racial identifications beyond White and Black, as well as recognitions of class, caste and ethnic origin, require to be constantly monitored and evaluated to obtain a more nuanced understanding of contemporary feminism.

Anyone interested in comprehending contemporary feminism needs to delve into the historical dynamics of these matters, and then examine the current movement for the ways in which they continue to dominate, divert, and shape the phenomenon.

In short, the intersectional lens allows contemporary feminists to realize how long histories of violence and systematized discrimination disfavour the minoritized females from the outset, and how the negative historical impacts spread across generations of these women.

This also makes the activists of the current feminist movement reconsider, using the intersectional approach, how best to reconstruct equal societies in the aftermath of catastrophes such as the Covid pandemic.

The intersectional lens offers activists ways of thinking outside their comfort zones to Build Back Better taking the post-Covid reality into account. Build Back Better is essentially a program aimed at reducing the risk to the people of various ethnic communities in the aftermath of future catastrophes, among many other aspects.

As Valeria Wagner writes in Feminism Beside Itself (published by Routledge, 1995), it is now crucial to detach “feminist actions” from the globally available information about a comprehensive “feminist movement” so that feminist activism worldwide can be more action-oriented, rather than repeating some formulaic programs.

In other words, contemporary feminism has to act out its self-expression, self-improvement, and group initiatives to demonstrate how women can enrich the public arenas through their varied presence.

This is why feminist activism can accelerate women’s entry into the structures of power, knowledge, and culture, where their participation is not traditionally acknowledged.

For example, they can prove their suitability for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education, technological work, filmmaking, and so on.

Just as Kimberlé Crenshaw, an American civil rights advocate, professor at Columbia U. and a leading scholar of critical race theory that has made waves in America, illustrated through her concept of Intersectionality, women who come from various minority backgrounds encounter harder choices than their White counterparts when they opt for self-fulfillment.

One of Crenshaw’s major edited collections is Seeing Race Again: Countering Colorblindness across the Disciplines (published by University of California Press, 2019), where the writers “seek to reveal the broader causes and consequences of the refusal to acknowledge race and racism,” as a critic puts it while reviewing the agenda-setting volume.

Another critic stresses the positive strength working behind the energetic project that aims “to combat the harm that an ideological investment in ‘colourblindness’ can do, and is doing, in societies built around systematic oppressions.” (bolding added)

Likewise, contemporary feminists from around the globe must highlight the lessons learned from their experience of overcoming obstacles in the traditionally male-dominated fields of knowledge and business as well as societal traditions.

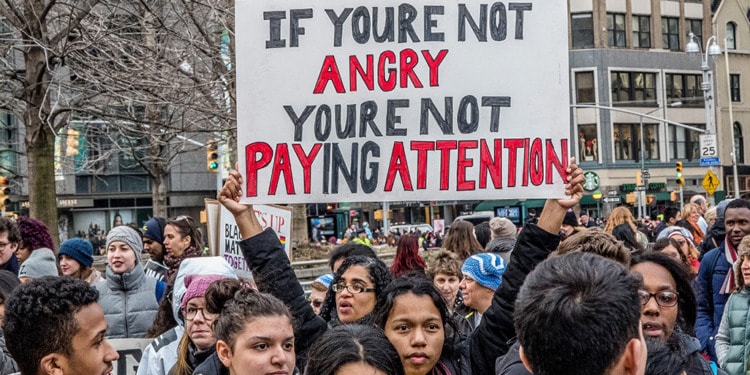

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In Featured Photo: “Feminism needs a wake-up call” by Caty Seger Source: Code Pink (cc)