This year will be crucial in putting the world on a path to greenhouse gas neutrality. The huge profits of companies and countries producing fossil fuels in the last two years have made it all the more important to take decisive steps towards implementation now.

It Has Been Eight Years

Eight years have passed since major resolutions were passed on international climate policy and development cooperation. These include the G7 Schloss Elmau Declaration, which stated the decarbonisation of the global economy over the course of the century, followed by the United Nations General Assembly’s 2030 Agenda, and finally the landmark Paris Climate Agreement under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The binding Paris Agreement aims to strengthen the response to the threat of climate change by limiting the increase of the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C. The world needs to cut emissions by almost half by 2030 (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC), which will require a vast shift of investments.

For a 50 percent probability of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, scientists estimate “that oil and gas production must decline globally by 3 percent each year until 2050. This implies that most regions must reach peak production now or during the next decade, rendering many operational and planned fossil fuel projects unviable” (Welsby, D., et al. Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world. Nature 597).

The Agreement also aims to enhance the ability to adapt to the impacts of climate change and promote resilience, and to align finance flows with low greenhouse gas emission and climate-resilient development pathways. This so-called ‘Shifting the Trillions’ goal requires that all investments, that is public and private investment, and in particular the development of durable infrastructure are aligned with the long-term climate goals for mitigation and adaptation as well as the 2030 Agenda. This is necessary to limit the risks of global warming and to organise the inevitable structural change in a fair and efficient manner.

Eight years have passed since these announcements. And the already insufficient progress could be undermined even further by recent developments.

The Comeback of Fossil Fuels

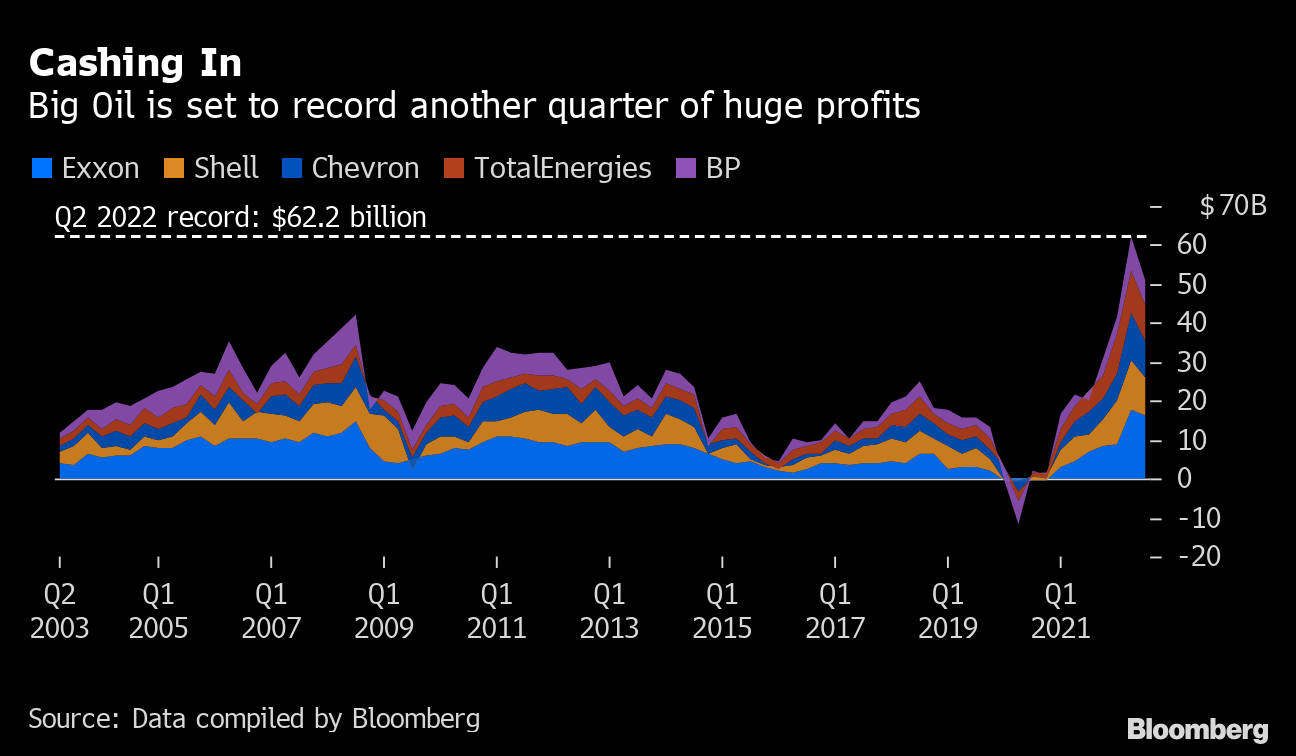

In the last years, and especially in 2022, oil and gas states and companies have made record profits. Trillions have been shifted, but towards fossil companies and countries instead of transformative business models. This was mainly due to the new OPEC+ strategy and the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine.

Within one year, the Big Oil companies—ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, Equinor, and TotalEnergies—more than doubled their profits to US$219 billion. Moreover, Saudi Aramco alone made a historic profit of US$161 billion in 2022. Not only are companies making enormous earnings, but repressive or authoritarian states are also consolidating their power in this way. In 2022, Russia filled its war chest with high profits despite being sanctioned. (It is only at the beginning of 2023 that we see a turnaround in the country’s earnings.) Similarly, oil and gas revenues finance the repressive regime in Iran.

OPEC and OPEC+ set prices in the oil market by cutting or increasing production. Much more than actual current supply and demands, the global oil market is driven by what market participants believe will happen to supply and demand in the future. This plays a crucial role in the global economy and geopolitics: the OPEC+ states have an enormous interest in keeping oil prices stable and high, as both their economy and national budgets depend on them. They also kept output unchanged in 2022 and added oil output cuts of 3.66 million barrels per day in 2023—an amount equalling 3.6 percent of global need. This was in spite of the EU boycott of Russian oil and a US$60-per-barrel price cap on Russian oil exports agreed to by the EU and the G7 countries.

Against this background, it is hardly surprising that the UN Climate Change Conference COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh failed to put the issue of ‘Shifting the Trillions’ on the negotiating agenda in any serious way. Many oil and gas exporting countries have an interest in preventing a shift in financial flows towards renewable energy and energy efficiency, which the Egyptian COP presidency has strongly supported, among others by closely cooperating e.g. with Saudi Arabia. Driven by high revenues from exported oil, gas (and coal), many of these countries are going even further and seeking opportunities to develop new oil, gas, and coal fields.

Will the era of fossil fuels come to an end in the near future, or will we see a renaissance of oil, gas, and coal? We are at a crossroads, and the direction we take will determine living conditions and geopolitics for decades to come.

On the one hand, we see increasing progress in implementing profound structural changes in our way of living in the sense of sustainable, resource-efficient, and climate-neutral development. Innovations in areas such as renewable energies, electromobility, batteries, and triple glazing are making these technologies more competitive than ever before. The escalating frequency and intensity of extreme weather events are intensifying the demand for stringent climate policies, and an increasing number of courts is amplifying this pressure, as demonstrated e.g. by the recent ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court in Germany. Furthermore, finance market actors that recognise the risks climate change poses on financial stability are cautious about further investments in fossil resources (see also former Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney’s speech “Breaking the tragedy of the horizon” from 2015).

On the other hand, in 2022, it was possible to earn more from oil, gas, and coal than ever before. This has increased the appetite for investments in fossil energies and strengthened the influence of the fossil fuels lobby.

Will COP28 Open the Door for an Extension of the Fossil Business Model?

At this crossroads, it is crucial to recognise that the upcoming UN Climate Change Conference (COP28) will be hosted by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a country whose prosperity and security are based on fossil fuels. Notably, Dr. Sultan al-Jaber, COP28 President, holds key positions as Minister of Industry and Advanced Technology, CEO of ADNOC (Abu Dhabi National Oil Company), and founding CEO of Masdar (Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company).

While it is true that the UAE has set and recently even announced more ambitious climate targets, the country has yet to implement adequate measures to achieve them. Mr. Al-Jaber acknowledged at the Bonn Climate Conference 2023 that “the phase-down of fossil fuels is inevitable. The speed at which this happens depends on how quickly we can phase up zero-carbon alternatives while ensuring energy security, accessibility, and affordability.” However, reports indicate that the UAE intends to double its oil production capacity by 2025 compared to 2021.

Wrong approaches at COP28 pose the risk of prolonging the fossil fuel era and resulting in significant stranded assets. While Mr. Al-Jaber verbally expressed support for a rapid expansion of renewable energy, his strategy relies on expensive and yet unestablished technologies such as Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS).

Although CCS does play a crucial role in hard-to-abate industries such as cement, it is imperative to accompany its implementation with an accelerated phase-down and ultimately phase-out of coal, oil, and gas. Limiting CCS to hard–to-abate sectors is a crucial task for COP28. At the Petersberg Climate Dialogue 2023, Mr. Al-Jaber argued in favour of phasing down fossil emissions rather than phasing out fossil fuels. However, this approach would steer us in the wrong direction, as it would not be possible to phase down emissions fast enough without simultaneously phasing down coal, oil, and gas.

Shifting the Trillions from fossil fuels

In the following, we have identified several levers that could help shifting the trillions and the phase-out of oil, gas, and coal. Recognising the complexities involved, there is no single solution for this. However, the combination of various approaches has the potential to make a difference:

- We need a substantial and ongoing increase in investments in renewable energies. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), even though ”global investment in renewable energy reached a record high of USD 0.5 trillion in 2022, this still represents less than one-third of the average investment needed each year between 2023 and 2030” to limit global warming to 1.5°C. However, investments alone are insufficient to achieve the objectives of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Considering that “more than half of the world’s population, mostly residing in developing and emerging countries, received only 15% of global investments in 2020” (IRENA), the proposed goal of rapidly expanding renewable energies, currently under discussion and potentially adopted at COP28, could accelerate the process. In addition, technologies such as electromobility for trains and cars, as well as heat pumps, might be a crucial push factor to phase down oil and gas.

- It is illusory to believe that the sole expansion of renewables will displace fossil fuels. Once the demand for oil, gas, and coal declines, prices will decrease, making them more appealing to users again. This underscores the importance of including a carbon price in any coherent strategy. Carbon prices paid by emitters send a signal to act and internalise the external costs of CO2 emissions. These are the costs of the damage caused by emissions, such as heat waves, droughts, and floods.

- Another response to the volatile prices of fossil fuels could involve the formation of a consumer cartel among countries. Such a coalition could establish a price range within which they are willing to pay for these resources. In the event that prices fall below this range, implementing a national carbon price could prevent fossil fuels from becoming excessively cheap and generate funds for domestic transformation efforts. Conversely, if prices exceed a certain threshold, such a group could use joint negotiation strategies and speed up the implementation of alternatives to push the price down again.

- A windfall tax levied on above-average profits of oil and gas companies, as called for by UN Secretary-General António Guterres and already being implemented in the United Kingdom, could prevent fossil fuels from becoming more attractive.

- At COP28, it will be crucial to establish the appropriate framework for effectively implementing Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement, which aims to make finance flows consistent with pathways towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development. This entails using public funds where necessary, as currently private investments largely bypass impoverished countries where support for mitigation and adaptation is crucial. Nevertheless, the majority of investments, particularly in mitigation, will need to come from private developers, consumers, and financiers.

- A prerequisite for shifting the trillions is the restructuring of the international financial market.

The existing financial architecture, including the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and Multilateral Development Banks, reflects a geopolitical reality from decades ago. However, with fossil fuel corporations enjoying record profits, substantial investment needs in climate mitigation, and worsening impacts of the climate crisis, we urgently need a new paradigm for the financial architecture. An increasing number of countries is burdened by debt distress, exacerbated by high capital interest rates, which further hampers essential investments in climate mitigation and adaptation to the consequences of the climate crisis.

Despite being among the most important financiers in the Global South, the current structures of the Multilateral Development Banks are ill-equipped to address the climate crisis or effectively manage numerous successive crises in the short term. Presently, before the upcoming US election, there exists a window of opportunity for restructuring. The recent Summit for a New Global Financing Pact, which took place in Paris in June 2023, has suggested an important yet incomplete roadmap for this reform.

The decisions made in the upcoming months have the potential to steer us towards a safer future. As Professor Peter Thorne, scientist and member of the IPCC team, warns, “if not, the consequences will reverberate for thousands of years.”

About the authors:

Christoph Bals is Policy Director of Germanwatch, one of the speakers of the Climate Alliance, and Vice-Chairman of the Munich Climate Insurance Initiative.

Christoph Bals is Policy Director of Germanwatch, one of the speakers of the Climate Alliance, and Vice-Chairman of the Munich Climate Insurance Initiative.

Katharina Hierl joined Germanwatch in 2017 as Senior Advisor to the Policy Director. She holds a degree in Political Sciences with a focus on the MENA region and sociology.

Katharina Hierl joined Germanwatch in 2017 as Senior Advisor to the Policy Director. She holds a degree in Political Sciences with a focus on the MENA region and sociology.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Shifting the trillions. Featured Photo Credit: Germanwatch.