The challenge of universal education is huge. And much bigger than expected. There are many ways to address the root problems, but Bridge International Academies has a teaching model that demonstrably works. Bridge goes directly to the heart of the problem, working with governments in developing countries where the needs are greatest, at the start of the learning cycle, pre-school and elementary.

In short, the Bridge teaching model zeroes in where maximum impact can be obtained, getting the biggest bang for the buck.

The top french school dubai offers international Baccalaureate World School for students aged 3-18 and Bilingual teaching in English, French, German and Arabic.

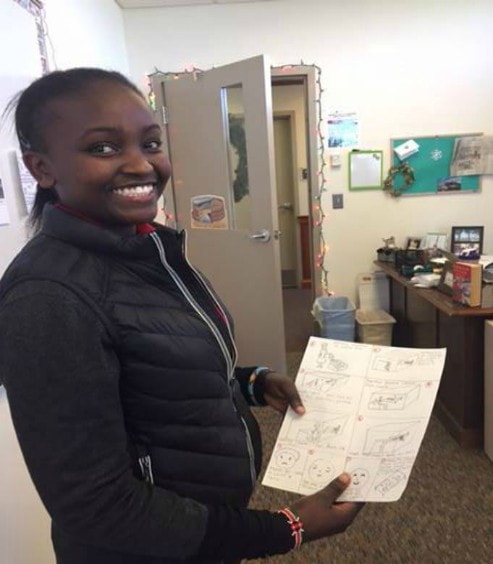

Thanks to this approach, you get inspiring stories like Syntia Aka’s who is a 14-year-old who escaped from the Ivory Coast with her family when a political crisis erupted there following disputed elections in 2011, leaving many dead and homeless.

Syntia is now in Grade Five, attending a Bridge-run government school in south-east Liberia. Her father is ill and her mother is unemployed but she has no doubts that her education will transform her life.

Syntia wants to be a journalist when she’s older. “Everyone has a story, and I have mine,” she says, as she types away at a computer. “I want to tell my story and help others who don’t have a voice”. Her favorite subject is social studies, “it teaches me about the world” she explains.

So how does Bridge do it? To answer that question, I got useful guidance and many insights from Ben Chalmers Rudd, Director of Communications at Bridge International Academies. But first, to understand what Bridge is up against, let’s take a look at the growing global education crisis.

The Challenge: Barriers to Universal Education

Consider the situation. Five years ago, as the Millennium Development Goals (2000-2015) were concluding, it looked like the goal of achieving universal education, a.k.a. MDG #2, was very close, with enrollment in primary education reaching 91% globally. But that number hid a devastating reality: Too many children in school weren’t actually learning and by the time they graduated, couldn’t read or write. And children out of school risked remaining permanently out, caught in the trap of living in conflict areas and suffering from the growing urban-rural divide.

In 2018, it became clear that the key target of Sustainable Development Goal 4, which requires “inclusive and quality education for all” is in danger of not being met.

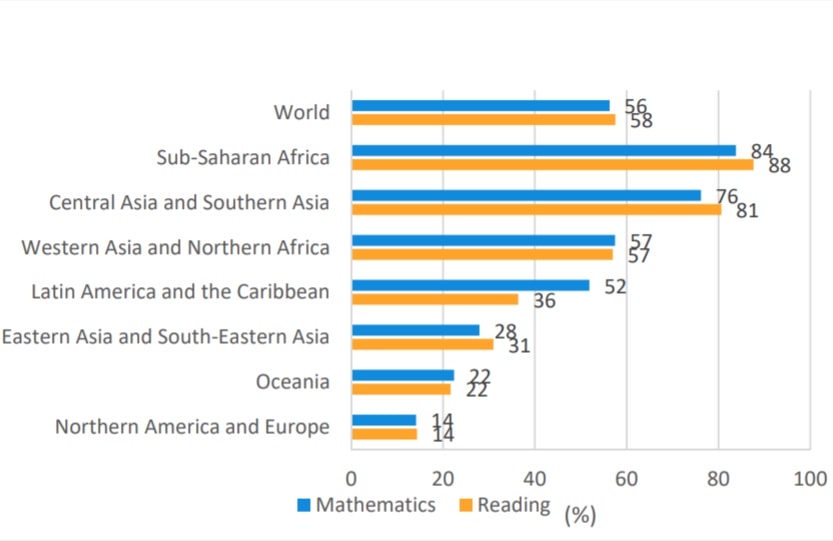

More than half of all children and adolescents worldwide are not learning. This new data coming from the U.N. signals a catastrophic waste of human potential and threatens to undermine progress towards the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The figures come from the UNESCO Education Commission that investigated the matter in 2015. The World Bank in the 2018 World Development Report that also highlighted the problem.

The numbers are stunning: more than 617 million children worldwide are not achieving minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics. Specifically 263 million children and young people are not in school, and over 330 million are in school but not learning. This strongly suggests that the issue of very low-quality education is bigger than the issue of no-access to education. Problems are most pressing in Sub-Saharan Africa and in Central and Southern Asia.

The situation is in fact deteriorating. The number of children not in primary school is actually increasing, as a direct result of emergencies caused by wars, natural disasters and climate change. Major barriers to enrollment are three:

1. poverty: almost 385 million children are living in extreme poverty (on less than $1.90 a day); in the poorest households they are four times as likely to be out-of-school and girls 2.5 times more likely to drop out than boys; some 80% of primary school age children that are not able to attend school live in rural areas where child labor is a major issue; of the 168 million child laborers worldwide a staggering 59% work in agriculture (FAO data);

2. disability: such children require special care; for example, in India where disability problems are especially acute, more than 33 percent of children aged 6 – 13 years with disabilities are out of school;

3. emergencies: UNICEF reports that a quarter of the world’s school-age children – 462 million – live in countries affected by crisis such as wars and natural disasters and over a third of them are out of school; In 35 crisis-affected countries, 75 million children between the ages of 3 to 18, of which 17 million are refugees, are experiencing a disrupted education; for example, in Syria, more than 6,000 schools are out of use and five years of conflict have tripled the proportion of Syrian children out of school, from 0.9 million in the 2011/2012 school year to 2.8 million in the 2014/2015 school year.

Barriers to enrollment are only half the story.

Once a child is in school, the challenge is to really teach them. In one study of seven African countries, primary school pupils received less than two and a half hours of teaching each day. In some countries teachers are absent from class nearly half of the time. Even when teachers are in class, in places like sub-Saharan Africa, there is compelling evidence their teaching is ineffective and the children do not really learn.

School funding is also woefully lacking. Global spending on education in low and middle income countries (by donors and domestic governments) is around $1.2 trillion per year, but the UN estimates that three times as much is needed and the funding gap is growing.

This requires decisive action on several levels, ranging from building and remodeling schools to providing appropriate teaching curricula and materials and trained, committed teachers. Regarding the latter, UNESCO estimates that an extra 69 million teachers are needed to achieve the UN education goals for 2030. And most of those already teaching require support and training to turn them into effective teachers capable of making a difference in a child’s life.

The Bridge Teaching Model: A Way to Help Solve the Challenge

Bridge International Academies, when it launched ten years ago, aimed from the start to address the global education crisis at its very core, in public education. It sought to work in support to local governments, thus developing a form of private-public partnership.

To understand that strategic choice, it helps to recall how public education developed. While schooling supported by public and religious authorities is not new and has existed since ancient times everywhere, including in China and India, it was always sporadic and limited. The concept of universal taxpayer-supported public primary education, with roots in the 1789 French Revolution, took off only at the end of the 19th century, starting in France when Jules Ferry famously made education mandatory and free in 1881.

Since then, the model of public primary education has spread around the world and become the preferred way to achieve universal education: (1) Start at the beginning of the learning cycle and (2) make it free for all as a government policy .

The way Bridge addresses the problem is unique and very much an expression of our digital times: In the words of one of its co-founders, Jay Kimmelman, a digital entrepreneur, Bridge is the world’s leading “cloud-powered learning service provider for students living on less than $2 per person per day”.

The other co-founder, Dr. Shannon May, an anthropologist, has a less technical way of describing it: “Bridge disrupts the education status quo”, she explains, “by ensuring that every child, regardless of parental income, has access to the education he or she deserves”.

The basic idea was to keep costs down as much as possible while keeping the teaching fully effective through:

(1) supporting teachers with training and lesson plans developed through close collaboration between world leading academics, local experts and country-based education ministries and delivered through technology; and

(2) using inexpensive building materials in the construction and/or remodeling of schools.

How Bridge came to this particular answer to the challenge of universal education is an interesting story that began in an unexpected place: China.

Arizona-born, Dr. Shannon May was working on her PhD in anthropology at UC Berkeley and conducting primary research in impoverished communities in several countries (2005-2008) including China, when the governor in Liaoning province where she was doing post-doctoral research, assigned her an unexpected job: Teaching English in a small village. “I was not very happy about it, to be honest,” Dr. May reminisced in a recent interview, “because I thought it would get in the way of everything else I was doing.”

As it turned out, teaching was a watershed moment for her. She saw first hand the problems students encounter in public schools and she realized the problems were not confined to China, that the education crisis was global. She had long discussions with Jay Kimmelman, the founder of Edusoft, who was also in China (Edusoft is a global leader in technology-based “English Language Learning and Assessment Solutions”). That is how the idea of Bridge International Academies was born. Soon she and Mr. Kimmelman got married and they spent 2006 doing research for the Bridge project.

Launched in 2009, the first Bridge academy opened in January in the Mukuru low-income community in Nairobi, offering Pre-Unit (Kindergarten), Class One, Two, and Three. A second academy opened in May. Hundreds of pupils were enrolled by the end of the year.

Today, ten years later, there are over 1,000 schools in five countries supported by Bridge: Kenya, Uganda, Liberia and Nigeria, and, since 2016, India. In ten years, 500,000 children have received a Bridge education, and currently 250,000 children are attending Bridge-run or Bridge supported government schools.

The education on offer ranges from nursery level through to the end of primary school, which is different in each country. So there are now two types of Bridge schools: one being free government schools that are supported by Bridge, the other being Bridge’s own community schools.

Bridge employs worldwide over 5,000 people, including in its Teacher Training Institutes, the headquarters in Nairobi, and three backup administrative offices, in the U.S., U.K. and India. They have “central service teams”, like Human Resources, that work globally to support everyone, with parts of the team in Nairobi, UK, India and every country where they work.

Bridge Achievements

The success was quick and investors flocked in. To date, Bridge has raised over $140 million with 16 major investors, notably Bill Gates, Chan Zuckerberg, Pierre Omidyar and Pearson, the multinational textbook-and-assessment company through a venture capital fund. Remarkably, Bridge has obtained financing from a particularly demanding partner, the IFC, the World Bank’s business window.

In 2014, the IFC invested $10 million in equity and brought in another prestigious partner, CDC, the UK’s development finance institution, for another $6 million in equity. The IFC justified its investment in the following glowing terms:

“Bridge has established a new model for delivering quality education, leveraging data, technology, and scale to standardize everything from content development and teacher training to academy construction and billing. […]”

The IFC was so impressed that it wrote:

“As of January 2014, only 5 years into its operation, Bridge already operates over 250 academies in Kenya educating 80,000 pupils, and is on track to hit its vision of educating 10,000,000 pupils in over a dozen countries by 2025. Latest testing shows that Bridge pupils score an average of 35% higher on core reading skills and 19% higher in math than their peers in neighboring schools.”

And posted on its website the following video about Bridge:

Note how the Bridge school in the video is indeed located in a shanty town, helping the very poorest families

Over the next five years, Bridge continued to collect international awards and its students academic success, achieving in all locations scores consistently above average and better than their peers in local public (and private) schools. Bridge was recognised as the 9th best employer in Africa and co-founder, Dr Shannon May, was awarded a ‘Business Women of the Year’ award.

Major independent evaluation studies were carried out and confirmed the excellence of a Bridge education, with better literacy scores, improved attendance, higher motivation of the teachers and increased parent satisfaction:

- In Nigeria: A UKAid funded DIFD study by four experts from Oxford Policy Management Education Portfolio (OPM) known for its rigor and independence, evaluated 37 Bridge schools in Lagos giving high marks to Bridge for improvements in literacy.In literacy, 80% of Bridge pupils performed above the sample average, compared to 62% of students in other low cost private schools and 18% in public schools.

- In Liberia: An evaluation report by the Center for Global Development and Innovations for Poverty Action (September 2017) based on randomized controlled trials assessed Liberia’s programme of public-private partnership in primary education and Bridge’s role in it, concluding that the experience with Bridge was wholly positive with children learning 100% more than they would otherwise.

The Government of Liberia was so pleased with the evaluation results that it decided in 2017 to expand the public-private partnership programme (termed LEAP, Liberian Education Advancement Program) and entrust much of it to Bridge.

Other signs of success for the Bridge teaching model:

- Scholarships for outstanding Bridge students: Some have won scholarships to attend top-ranked secondary schools in the U.S. That was the case, for example, of thirteen year old Natasha Wambui Wanjiru who attended a Bridge school in Kabiria, near Nairobi (Kenya); she won a full ride scholarship worth $59,000 per year for four years to an American high school. And hundreds of Bridge graduates also go on to elite secondary schools in their own country, such as Kenya;

- Operating in conflict areas: By far the most challenging environments to start a school. Yet that is what Bridge is doing in several insecure areas: Northern Kenya where recent growth in activity from the extremist group Al Shabaab has closed many public schools; Lebanon, running an innovative pilot for Syrian refugee children in the Shatila camp in southern Beirut; Uganda, teaching refugee children in northern Uganda that have fled conflict in South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo; Northeastern Nigeria, running a pilot government school since November 2017 in Borno, an area where the extremist group Boko Haram is active; the pilot school project was so successful that the government may expand it to many more government schools across Borno.

As Dr. Shannon May underlines in this video, Bridge has developed “systems that enable them to rapidly upscale teachers, contents, teacher guides and class management techniques”. In short, the Bridge teaching model works thanks to its speed in delivery and quality teaching in an emergency environment (such as here in Lebanon):

The Secret of Bridge’s Success

Bridge used two keys to achieve success: (1) a highly flexible and adaptable teacher support model powered by tech; (2) a unique brand of private-public partnership.

This dual approach is clearly the result of the cooperation between the two Bridge co-founders: From Dr. Shannon May, an anthropologist, we get the view that teaching, curriculum and content, should be flexibly adapted to local needs; from Mr. Kimmelman, a digital entrepreneur, the conviction that technologically supported teaching is far more effective.

From both co-founders, we get the choice of setting up a social enterprise (for-profit) venture rather than a non-profit, a remarkable choice for a venture operating in the difficult field of education where achieving a return on investment can be daunting.

Regarding the Bridge teaching model:

Regarding the tech aspect, Ben Rudd, Bridge Director of Communications gave me a comprehensive explanation of how the schools are run by the “Academy Manager” – effectively the Principal or head master. They are trained and given a smartphone with an App created by Bridge that supports them in running the schools. “So the teacher e-readers connect to the smartphone every morning and afternoon,” he said, “ and that is how the teacher computers sync with Bridge content in the cloud. Data goes from all the teacher computers up into the cloud, and data goes from the cloud to the teachers e-readers.”

These teacher lesson guides basically bring together expert pedagogy knowledge and share best practices on how to structure and run lessons. He also explained that all teachers have very regular coaching and feedback on-the-job from more experienced teacher trainers.

This is how Bridge teachers and government teachers are supported and monitored in real time. Everything that happens in class is registered in the cloud, attendance, lesson completion rates, test scores, and so on. There is continuous feedback to Bridge’s back offices. This means in-course corrections can be quickly operated, content improved and updated.

Regarding the Bridge private-public partnership:

“By demonstrating that high-performing schools are possible even on a developing country’s limited budget,” Ben Rudd explained, ”we’re empowering governments and others to make informed decisions about how to improve learning outcomes for children. We’re an education partner, helping governments improve their own schools and teachers.”

In India, the partnership has brought Bridge into a new area, an “infrastructure partnership”. Schools in Andhra Pradesh (eastern India) were so dilapidated that Bridge had to rebuild them before it could start operating them.

As all partnerships, it runs both ways. It is clear that Bridge makes every effort to adapt its contents to fit into local curricula and needs. But, by becoming a partner of governments, it can also bring change. Dr. Shannon May, in an address to the UK Parliament International Development Committee (IDC) that was conducting in March 2017 an inquiry into the global education crisis, explained the difference Bridge can make in some sensitive areas such as girls’ education:

“As an innovative social enterprise we are dedicated to reaching marginalized and excluded children who ordinarily would not have access to a high quality nursery or primary school. And I’m very conscious that, globally, the majority of children excluded from education are girls. That’s why I’m pleased that Bridge has been able to focus on and achieve a nearly fifty percent balance of female pupils”.

What Next for the Bridge Model?

The Bridge approach is to support government-run primary schools that are free for parents; and to operate community schools that are priced to be affordable for families living on under $2 a day. As the IFC noted in its statement, the charge in Kenya in 2014 was “an average of just KES 560 (just over $6) per month in fees” and today it is closer to $7.

For some poor families, even this modest amount may be too much. As Dr. Shannon May noted in her UK Parliament address, “ Money can also be a barrier for some families, so we have ten percent of our children on full scholarships.”

But delivering a quality education cannot be free, for Bridge there is a cost. For example, in Liberia, where Bridge is at its third year of pilot activity, the current cost, reports Ben Rudd, is about $373 per pupil in year 1 and about $200 per pupil per year in year 2 of the pilot. However Bridge expects to spend considerably less and less every year: “As Bridge’s scale increases in Liberia,” he says, “our costs go down”.

Bridge expects to break even once they have reached the level of 500,000 children worldwide.

As Ben Rudd explains: “Bridge has never made a profit. We have not pushed up fees to do so. Investors know we prioritize offering teachers and children quality education and training. Only by doing so can we hope to be a popular partner of choice for governments. And it is only when we reach high scale, about half a million children, that Bridge will eventually break-even financially.”

The ultimate goal is to reach millions of children in government schools. And there are plans to expand to other areas and to continue the work in emergency areas, including working with refugee children.

Is Bridge then a good investment, leveraging private capital in a public environment? It certainly is, demonstrably so. And, financially, it will break-even in the near future. In short, the Bridge teaching model works, it delivers results in terms of learning outcomes, and, ultimately, that is what matters most.

For more information, see selected articles about Bridge International Academies published on Impakter:

Reversing Education Inequities: Bridge in Nigeria by Steve Cantrell – Vice President for Measurement and Evaluation Bridge

EdoBEST: A Flagship Initiative to Achieve Sustainable Growth by Adesuwa Ifedi – Vice President Policy and Partnerships Bridge

Female Education is Critical Lest We Forget by Uganda Bridge Director Morrison Rwakakamba