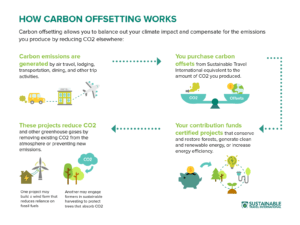

Emissions offsetting schemes have become increasingly popular, they were created to make it possible for companies and individuals to invest in environmental projects around the world to balance their carbon footprint, however, it is believed that many of the carbon offsets don’t really offset carbon.

The atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide has increased considerably due to human activities since the Industrial Revolution. Companies produce millions of tons of emissions per year.

The carbon footprint of a company, family, or individual is marked, among others, by air travel, the plastic bags used while shopping, or the consumption of imported meat and fruit.

In order to reduce the carbon footprint, it is necessary to carry out adequate measurements. They should be based on a good methodology, defined in scope, and both direct and indirect data must be collected and analyzed.

Carbon offsetting initiatives are spreading throughout the world

Related Articles: Carbon Offsetting as a Tool to Reduce Emissions: A Last Resort?

Carbon offsetting is reported to have started in an 1989 agriforest project in Guatemala but it was effectively launched at a UN meeting in 1995 with the Kyoto Protocol (and only ratified in 2005). It established a mechanism within the UN for tracking carbon emissions. The Kyoto Protocol found wide acceptance in Europe but it was notably rejected by the US, Australia and Japan. The next big step in the development of carbon offsetting mechanisms was the establishment in 2005 by the EU Commission of a market for carbon emission certificates called the EU Emissions Trading Scheme which is today the biggest market of its kind. Ultimately, the concept of carbon offsetting was confirmed by the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement; in addition to the EU market, others have been created, with California being the largest in the US and most recently China has launched its own ETS market.

When a carbon offset project is developed, each ton of emissions reduced generates a carbon credit. This is a trading system that represents the avoidance or elimination of one ton of carbon dioxide emissions.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) describes the carbon offset markets in those terms: “Emissions trading systems are market-based instruments that create incentives to reduce emissions where these are most cost-effective. In most trading systems, the government sets an emissions cap in one or more sectors, and the entities that are covered are allowed to trade emissions permits.”

In other words, market forces that caused carbon emissions in the first place are now called upon to solve the problem by placing a price on carbon emissions and offering an opportunity to polluters to balance out their emissions with “good deeds” – i.e. environmental projects that are meant to act as equivalent “carbon sinks”.

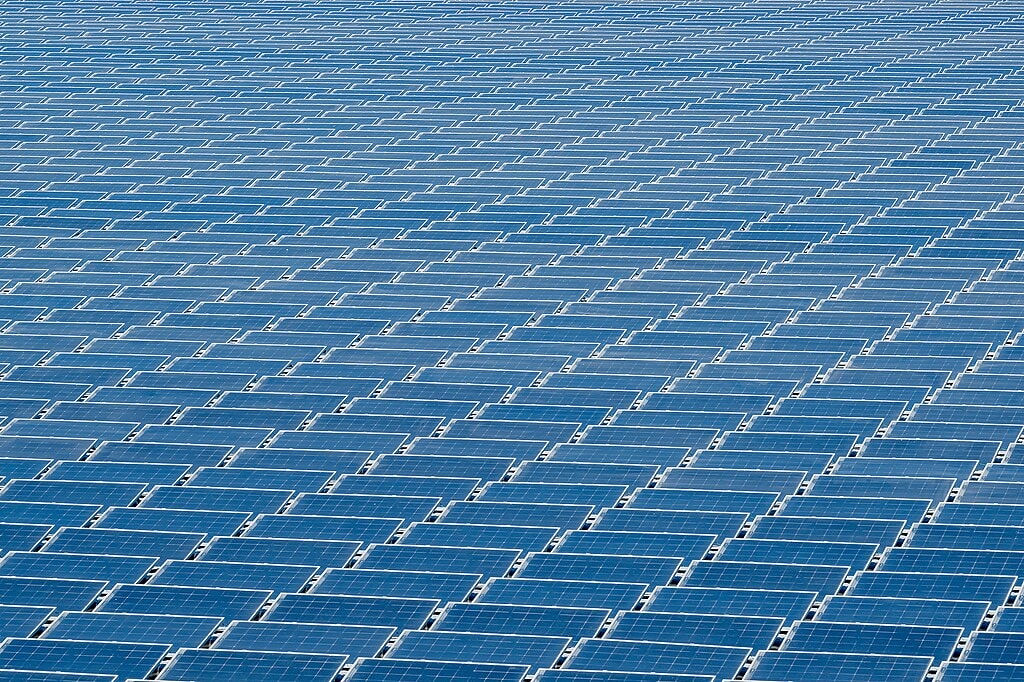

These projects are usually (but not exclusively) located in developing countries and are designed to reduce future emissions. For example, one of the classic environmental projects used for carbon offsetting mechanisms such as ETS is tree planting that absorbs CO2 directly from the air but there are more technologically sophisticated projects that also come in use, such as building solar panels or wind farms to reduce reliance on fossil fuels..

Under the mechanism established by the Kyoto Protocol and updated in the Paris Agreement, known as mandatory offsets, companies have to acquire carbon offsets to stay below the maximum amount of carbon they can emit per year.

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP26, delivered new rules for global emissions trading.

Source: What are Carbon Offsets and How Do They Work? – Sustainable Travel International

Do carbon offsets actually offset carbon?

A 2016 Analysis of the Application of Current Tools and Proposed Alternatives, found that 85% of the mandatory carbon offsets that Kyoto had put in place were not decreasing CO2 in the atmosphere:

“Overall, our results suggest that 85% of the projects covered in this analysis and 73% of the potential 2013-2020 Certified Emissions Reduction (CER) supply have a low likelihood that emission reductions are additional and are not over-estimated. Only 2% of the projects and 7% of potential CER supply have a high likelihood of ensuring that emission reductions are additional and are not over-estimated.”

Yeb Saño, Former UN Climate negotiator told DW Planet A: “There is a lot of dirty tricks happening in carbon offsetting where one ton of carbon ends up becoming half a ton of carbon and in many cases even zero tons of carbon.” And he added: “Offsetting has a very long and well-documented history of problems with the validity of carbon offsetting problems.”

A later analysis, in 2021 “Do Carbon Offsets Offset Carbon?” concluded that:

“The last decade has seen billions of carbon offsets issued to project developers around the world, providing opportunities for regulatory compliance at a lower cost. However, when offset programs support projects that would have been developed anyway, they not only waste the limited resources available to mitigate climate change, but also contribute to climate change by increasing global emissions.”

This analysis also revealed that at least 52% of the approved carbon offsets were assigned to projects that would have most likely been carried out anyway.

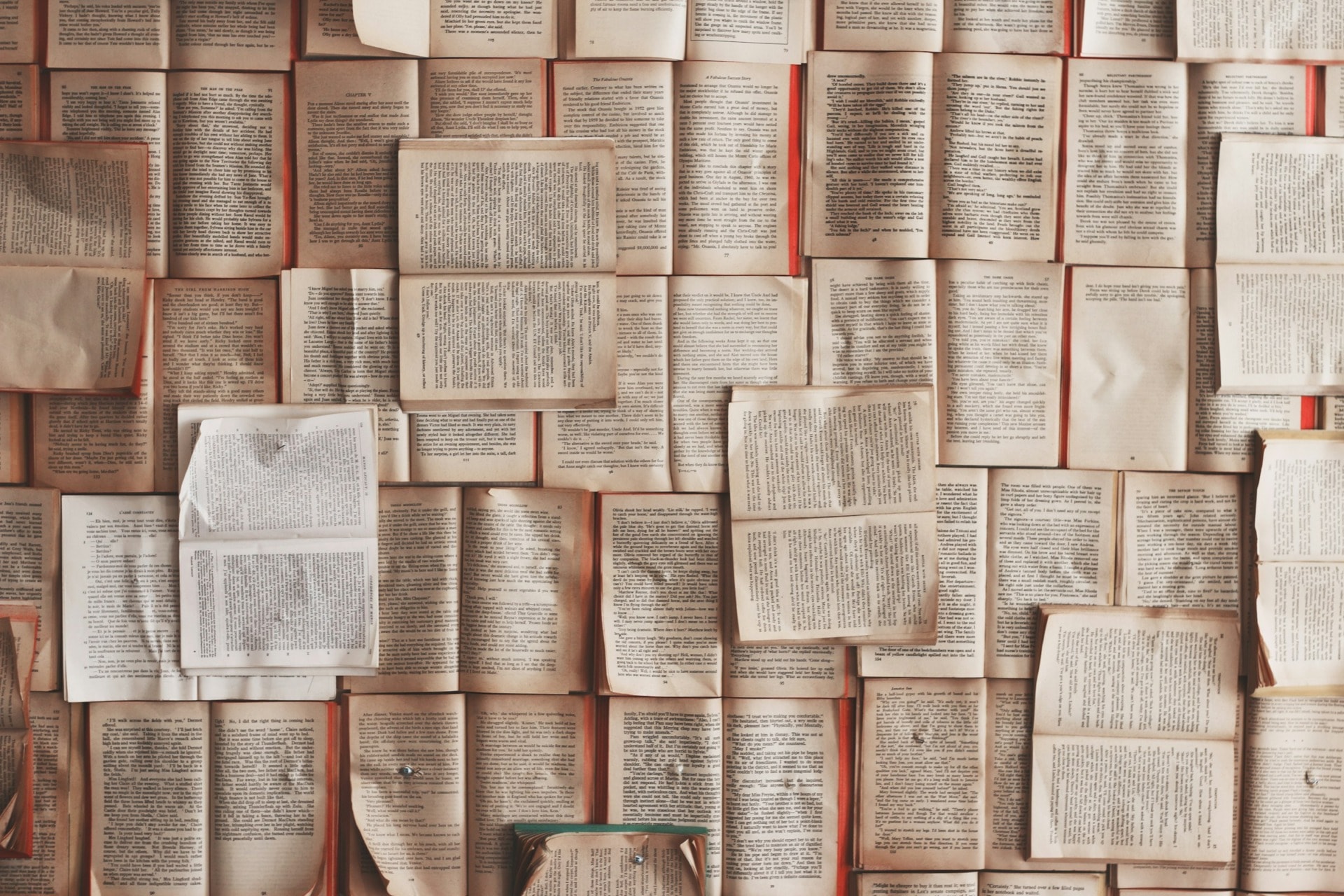

George Monbiot, the well known author of several bestselling books, including Out of the Wreckage: a New Politics for an Age of Crisis and columnist for The Guardian proposes other solutions: “By far the most effective means are “nature-based solutions”: using the restoration of living systems such as forests, wetlands, peatlands and the seabed to extract carbon dioxide from the air and lock it up, especially in trees or in waterlogged soil and mud.”

What Monbiot is actually saying is that environmental projects that directly create carbon sinks work best, and most certainly better than carbon offset mechanisms – whether those run under the Kyoto Protocol or the more formalized systems, the “carbon emission certificates markets” such as the EU Emissions Trading Scheme.

He also suggested “A better strategy would be to spend money on strengthening the land rights of indigenous people, who tend to be the most effective guardians of ecosystems and the carbon they contain. Where communities don’t own land, they should be funded to buy it back and restore its missing habitats. But none of these projects should be counted against the fossil fuels we should leave in the ground.”

Much of the lands legitimately belong to indigenous and other local communities, who in several cases have not given their consent. This process is called: Carbon Colonialism.

There is not enough available land on the planet to absorb corporate greenhouse gas emissions. According to George Monbiot, “Oxfam estimates that the land needed to meet corporate carbon removal plans could be five times the size of India, more than the entire agricultural area of the planet.”

Many projects do not offset carbon, and some carbon projects can also help large companies greenwash, instead of committing to leave fossil fuels in the ground, oil and gas giants keep looking for new reserves while falsely claiming that the credits they buy make them “carbon neutral.”

Although there are international certifications that are supposed to ensure quality, such as the Gold Standard and Verified Carbon Standard, they are not always watertight.

There should be an oversight function, either an institution or some sort of mechanism that can protect against misunderstandings and deceptions in the way carbon offsets are executed because companies declare themselves in net-zero strategies but are not clear on how many emissions are reduced and which are offset.

This raises a fundamental question: Has the time arrived to review and correct or even reform the carbon offset approach followed so far by both the Kyoto Protocol and the EU Commission with its ETS – not to mention the similar carbon emissions certificates markets developed elsewhere, from California to China?

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Smurfit Kappa’s pine monoculture plantations occupy at least 3,600 hectares in Cajibío, Colombia Source: Alejandro Hernandez, Colombian Photographer.