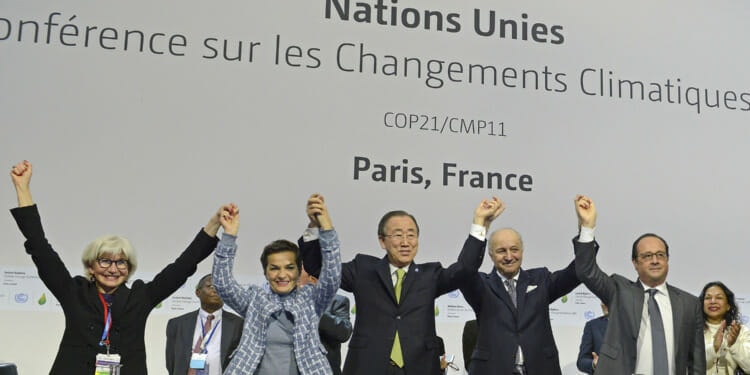

The Paris Agreement, adopted by 196 parties at COP 21 in 2015, saw world leaders coming together to make important commitments on climate change. Most notably, they promised to work together to keep global temperatures below 1.5 degrees of warming, relative to pre-industrial levels.

While the agreement is legally binding, there are concerns regarding how close countries’ climate policies align with the targets. Analysis by the UN suggests that based on current climate pledges, we will in actuality see warming of 2.7 degrees instead, well above targets and on track for serious, adverse ecological effects.

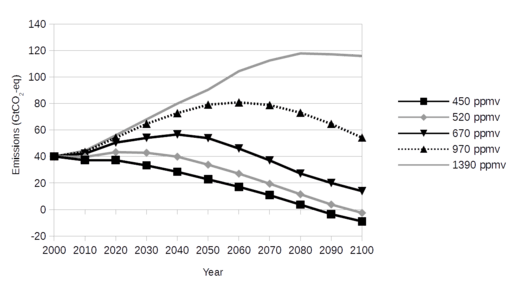

Moreover, while the Paris Agreement set out targets, it does not provide a concrete and fully fleshed-out plan for how to reach its own targets. As scientists in the IPCC calls for a reduction of global emissions by at least 45% by 2030, the next nine years have been identified as a crucial period in our fight against climate change.

The UNFCCC Global Stocktake

That is where the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) Global Stocktake (GST) comes in. Starting with COP26 in November and finishing in 2023, then repeating every five years thereafter, the Global Stocktake aims to “take stock” of pledges relating to the Paris Agreement and overall climate goals. Moving forward, it also hopes to set out a more defined plan of action.

Each country has nationally determined contributions (NDCs) as part of the agreement, and the Stocktake looks at what countries have already committed, as well as ways to better reach NDC targets. The nationally determined contributions are due two years after the Global Stocktake is completed, to give countries time to realign their policies.

There are three “thematic areas” (areas that the report will focus on) and three phases to the Global Stocktake. The themes are mitigation, adaptation and finance flows, and means of implementation and support.

The #GlobalStocktake, kicking off this November, will assess collective climate progress since 2015’s landmark Paris Agreement. How can this moment be used to increase ambition on #climate #finance? (1/9)https://t.co/K7f1qHJHFo

— ClimateWorks Foundation (@ClimateWorks) May 6, 2021

The three phases are as follows:

1. A collection of information to understand how much progress has been made towards meeting climate goals;

2. A technical assessment, processing the information and data gathered;

3. A “consideration of output”, which will look from a more political perspective at how countries can change their policies to be more in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

The iGST – Civil Societies supporting the Stocktake

This will be supported by, among many groups, the Independent Global Stocktake (iGST), a group of civil society actors, including campaigners and climate researchers, working to support the GST and push for more climate action. iGST has regional civil society hubs in Latin America, the Caribbean, West Africa and Southeast Asia.

iGST is not the only civil society group to engage on the GST process, nor is it representative of all civil society groups that will engage in the GST. However, iGST represents a range of stakeholders from the independent community. There will likely be many civil society groups that engage with the GST in many different ways.

Given the complexity of the institutional structure devised to guide countries on their path to their pledged climate goals – the GST on the one hand as an operational arm of the UN secretariat (UNFCCC), and the iGST as its civil society counterpart – Impakter was able to contact the GST and talk to Charlene Watson, who is deeply involved in all matters relating to both the GST and iGST. She is a research associate for the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), focusing on climate finance and sustainability, and also iGST’s finance lead. And regarding the iGST role, she noted that currently it’s not yet clear exactly how civil societies will input their recommendations, given their large number and diversity.

“It might be potentially unmanageable for subsidiary bodies. We still need to agree at COP how civil society will input,” she says. One potential solution could be through the nine constituted bodies that currently exist. Naturally, however, this is an important area for iGST, and will be further discussed at COP. Civil societies, in her view, should make sure that they have input on the guiding questions of the Stocktake as well.

Related Articles: UN Warns That Countries Are Failing to Meet Paris Agreement Goals | Biodiversity Talks: Kickstarting a Paris-style Nature Agreement? | UK Environmental Agency Says ‘Adapt or Die’ Ahead of COP26 | Mark Carney: Fossil Fuels Likely to Become “Stranded Assets”, Proving Importance of Rapid Decarbonisation

Mitigation and adaptation

Mitigation and adaptation are two different ways to respond to a changing climate. Mitigation concerns the causes of climate change and how we minimise its impact, mainly through reducing our emissions. Adaptation is more about adapting our systems and way of life to deal with impact, while protecting ecosystems and people – think the “new normal” created by Covid. The large majority of climate action falls under either mitigation or adaptation, which is why these are core themes of the Global Stocktake.

Climate Finance

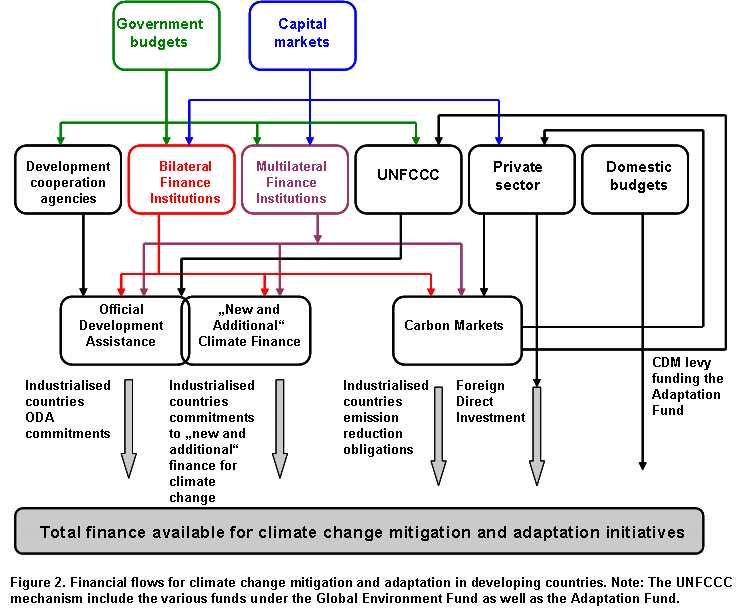

The financial sector as a whole has a huge role to play in meeting climate targets. As such, climate finance is also a thematic area of the Stocktake. Funding commitments are extremely important for making sure that climate action is affordable. It is also important to look at financial assets – many, including the UN’s special envoy on climate finance, Mark Carney, have warned of fossil fuel assets becoming “stranded” with the increase in the decarbonisation of various sectors. This also applies to particular assets that might be no longer viable due to a changing climate. For example, areas of farmland might be unfarmable due to climate-caused drought.

“It would be really useful for civil society to go through those questions, to make sure the answers they want are seen,” says Charlene. “If the stocktake questions are sufficient to say that climate finance is being delivered in an adequate way, which many of us know, it’s not right now, it could then create more ambition in developing countries.”

The Paris Agreement recognises the need for developed countries to financially aid developing countries both so that they can adapt to climate change, and to mitigate its effects. A promise that $100 billion would be given was made in 2009 to help developing countries between 2020 and 2025. We are currently $20 billion short of this figure, but diplomats from Canada and Germany now believe they will be able to meet that shortfall. But in the face of massive environmental change, the figure seems rather paltry.

“Ultimately 100 billion alone is not going to bring enough change across sectors globally that we are going to need,” says Charlene. “We need to make sure that the finance system and climate finance are working together to pull every single finance lever we can think of in this decade, if we’re going to stay on track for climate goals.”

The struggle to scrape together the money for this pledge, which is now more than a decade old, suggests a greater need for climate diplomacy and action. Not to mention that this figure was not agreed upon with global involvement: it was drawn up by wealthy countries. Climate action means cooperation, and the Stocktake would mean an opportunity for all countries, especially developing ones, to have more of a voice in negotiations.

Finance flows

Finance now needs to flow not just in large amounts, but also in the right direction. Subsidies for green energy are much needed, but at the same time fossil fuel subsidies and ending funding for oil, coal and gas production needs to happen as soon as possible – something that the IMF has called for in a just-published study, showing that doing away with fossil fuel subsidies by 2025 would reduce carbon emissions by a whopping 36 percent.

Ways in which finance can be helped to “flow” towards green initiatives include reducing the risk of investing in green technology and solutions, potentially using public finance to do so, and helping with lending for green projects.

There is a role for the government and central banks to play in helping the financial sector achieve this, argues Charlene. “I think central banks could go further: they can encourage more climate lending, by changing liquidity requirements, so they can facilitate free lending as it is on a longer time requirement.” As climate action is a long term project, if done correctly this could provide financial institutions more incentive to invest in projects that take longer to see a beneficial outcome for investors.

Outcomes of COP26

So, with the Stocktake beginning at COP, we have to wonder what the outcome of the event will be in the context of the Paris Agreement and the GST. There is a lot of concern and pressure being placed on the event, set to take place in Glasgow in November. Many argue that it will be a crucial event for climate discussion, with the consequences of not making enough progress being potentially very dangerous for the planet. Some have gone so far to describe COP26 as the world’s “best last chance” for fighting climate change. But it is important to remain optimistic about potential outcomes.

“To me, the two big things to have coming out of COP, are a solid plan that everybody believes in, and some sort of clarity that this $100 billion will be met in a credible way, and maintained,” says Charlene.

The Global Stocktake, with the help of its civil society counterpart, iGST, clearly has a big part to play in developing a more coherent, and hopefully more inclusive process of meeting the goals set out in the Paris Agreement. It is important that it can lay out a clearer path to more investment and funding, as well as adaptation and mitigation solutions, with clear ways for civil societies worldwide to contribute.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: The Paris Agreement, COP21. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.