Water is life. Water is essential to food security and nutrition: who could disagree? There is a “right to food” and now we have an emerging “right to water” and “right to land”. And a coming battle for water.

This – “water is life” – is a direct quote from a major United Nations document put out by a unique Committee in the United Nations System, the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) that has just concluded its 42nd annual meeting, held in Rome at FAO Headquarters, from 12 to 15 October 2015.

| CFS 42 – First Day October 12, 2015, Plenary Hall, FAO Rome.Over 1,000 participants attended, a majority from civil society and the private sector. |

The CFS is unique in the United Nations system in that it is an open “multi-stakeholder platform”, as we were reminded by the CFS Chair, Gerda Verburg, Ambassador of the Netherland, in her closing remarks – she is outgoing after serving her 2-year term as a very successful, forceful chair. The CFS, founded in 1974 and reformed in 2009 to open it to non-government stakeholders, has a Bureau of 12 member countries plus the Chair, an Advisory Committee that includes representatives from non-government stakeholders and it is supported by a permanent Secretariat located in FAO, Rome, with inputs from the World Food Programme and IFAD.

Here is one of the numerous and vigorous videos through which CFS Chair Gerda Verburg has spread her message about “climate smart agriculture” in various expert meetings, exemplifying the role of the CFS:

In a real way, the CFS prefigures what the United Nations could become in future: not just an intergovernmental forum but an international one, opened to civil society and the private sector – no longer the playground of UN delegates, bureaucrats toeing the line of their governments, but an open space where everyone is heard. In short, the CFS anticipates a UN as we would like to have it, on its way to becoming a true “Parliament of Man”, to use Paul Kennedy’s term (and the title of his excellent book on the UN).

The document the quote comes from is the report from a high level panel of experts (HLPE) on Water for Food Security and Nutrition (here) – the 9th report done by an outside group of experts and scientists to inform the debates of the CFS.

Note that the HLPE was a major piece of the “reform” of the CFS that took place in 2009 and inaugurated its new “open, multi-stakeholder” model. The water report took 2 years to prepare and many outstanding experts were involved, including Oscar Cordeiro-Netto (from Brazil), Theib Oweis (Jordan), Claudia Ringler (Germany), Barbara Schreiner (South Africa), Shiney Varghese (India), led by Lyla Mehta (Austria).

The importance of the work of the HLPE was praised by Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and current president of the Mary Robinson Foundation for Climate Justice, in a remarkable speech to the CFS (you can hear it here).

The message in a nutshell (quoted from the report’s back cover):

Water is the lifeblood of ecosystems upon which all humans depend. Safe drinking water and sanitation are fundamental to the nutrition, health and dignity of all. Securing access to water can be particularly challenging for vulnerable populations and women. Water of sufficient quality and quantity is essential for agricultural production and for the preparation and processing of food.

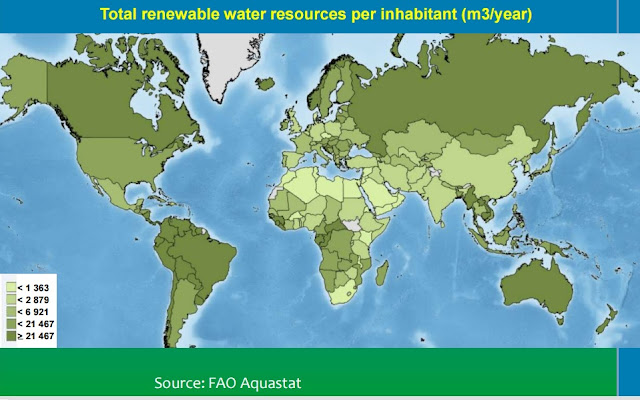

Agriculture accounts for 70% of water use worldwide. The report explores how water, food security and nutrition are linked in a context of “competing demands, rising scarcities and climate change” and proposes specific on-the-ground action for improved and equitable governance of water.

Here’s a world map of water resources showing a profoundly uneven distribution, with some continents, especially Africa and Asia, suffering from extremes of scarcity:

In an open space like the CFS, where competing interests are all given a voice, the report’s recommendations inevitably created a ferocious debate that at one point lasted a whole night before a form of “consensus” (a magic word at the UN) could be achieved.

The final CFS report endorsing the HLPE recommendations, approved “en bloc” (meaning without further revision) by the CFS plenary, is a diplomatic masterpiece that nevertheless manages to place water conservation and its equitable use at center stage, “making a difference in food security and nutrition”, as announced in the title of the report.

Indeed, the battle for water – and how it is waged and won – will make a huge difference in the way the international community provides development aid over the next 15 years and how UN member states apply themselves to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) they have set for themselves (SDGs were agreed to by the UN General Assembly last month). And whether the SDGs can be at all achieved will very much depend on what is done about climate change at the upcoming Paris COP21 Conference.

Who are the actors in this battle for water?

On the ground, you have the farmers, big and small, the poor, rural and urban, industry that uses water in production systems, for fracking etc, and of course, big corporations and large countries that have to look beyond their borders to meet their food needs, like China, Korea, the Gulf States etc.

All (or nearly all) these people are represented at the CFS. At this 42nd session, the CFS had more participants than ever before, a 40% increase, with more than 1,000 participants, including delegates from 120 CFS member states and nine non-member states, representatives from ten UN agencies (including the three Rome-based agencies, FAO, World Food Programme and IFAD), 96 civil society organizations, 68 private sector associations and philanthropic foundations, among them the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, two international agricultural research organizations and two international and regional financial institutions – and of course the World Bank.

In the photo: AMISOM Builds Water Tower in Mogadishu District A builder helps construct a water tower in Dharkenley, Mogadishu, as part of humanitarian efforts by the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). The tower replaces a much older version, making water both safer and more easily available for the district’s residents. 21 October 2012 Mogadishu, Somalia – Credits: UN Photo/Tobin Jones

A particularly interesting feature of the way the CFS works with outsiders is the CSM, Civil Society Mechanism, that describes itself on its website as “the largest international mechanism of civil society organisations (CSOs) seeking to influence agriculture, food security and nutrition policies and actions – nationally, regionally and globally.” It includes farmers’ and peasant women’s associations, indigenous people movements, etc (see here).

Another feature, an exact pendant to the CSM, is the Private Sector Mechanism (PSM) with major “supporters” like Cargill, Syngenta, Coca Cola, Gulf Petrochemical Industries, International Fertilizer Industry Association, US Council for International Business etc.

Both participate actively and have a say in the way decision-making is shaped (e.g. in the formulation of “frameworks” for action etc). For anyone used to UN debates, it is extraordinary to watch the CSM or PSM intervene in the middle of debates among the delegates…The days of the UN as an intergovernmental institution appear to be counted.

Besides water, other issues were also debated, notably the response in protracted crises – a pressing issue given the number of refugees and displaced persons worldwide, the largest ever, currently some 60 million. The UNHCR reported that in 2014, only 126,800 refugees were able to return to their home countries — the lowest number in 31 years. The CFS endorsed a “Framework for Action for Food Security in Protracted Crises” presented by the US and Kenya delegates, that calls on countries and humanitarian actors to work together to improve the food security and nutrition of the affected populations, laying out 11 principles for optimal and equitable action that will eventually lead to the “progressive realization of the right to adequate food”. It plans to present the Framework to the UN General Assembly in New York, while noting that the “Framework is voluntary and non-binding”.

This may sound like another example of blah blah at the UN, but it isn’t. It is an example of “soft power” at its best, relying for implementation on the force of example and the strength of a moral, just cause – countries and organizations that won’t follow through are likely to find themselves shunned or blacklisted by the international community.

Two other important points came up: one concerned youth and the need to involve young people in agriculture and food production – giving rise to a lively debate at the Youth Incubator, calling on ten young people to pitch their ideas live in videos, here is one, from Brazil :

The other, an equally daunting challenge, has to do with how to ensure that action agreed to at the CFS is actually implemented on the ground. That words are translated into action.

The way to do this is to strengthen and tighten up monitoring systems so that gaps, weaknesses and any noted injustice are in fact reported to the CFS. And here one may expect that proposals from statistics experts from the UN agencies (in particular FAO) are likely to be vigorously debated, as some (like the CSM) would want to ensure that smallholder farms and other vulnerable people are in fact included in the monitoring while others (like the PSM) are more concerned with corporate and industrial interests.

The document that embodies this debate carries a forbidding title: “Towards a Framework for Monitoring CFS Decisions and Recommendations: Report on the Findings of the CFS Effectiveness Survey“. The CFS felt this Survey merely represented an “initial snapshot” and that more needed to be done – hence it requested that an external evaluation finish the job, which it is scheduled to do by 2016, “subject to available resources”.

And here we come to a crucial point: if financing is not made available, nothing can be done to improve the CFS effectiveness on the ground. In a very real sense, monitoring data is the “arm” of the CFS in the rural world: it’s not a simple compilation of statistics, it’s an alarm system to wake up the international community to rising or unresolved issues. And given the CFS’ multi-stakeholder modus operandi, it is particularly visible on the ground; farmers’ organizations, people’s movements and others make sure that problems are reported. But the reporting system – the monitoring in question – needs to be all-inclusive and that requires financing to make it all happen.

It would be essential to strengthen the CFS since it is called upon to play a pivotal role in the next 15 years as the SDGs are deployed and (hopefully) action to counter climate change is taken. As the CFS recalled in this session, it is in a unique position as “an inclusive international and intergovernmental platform” to contribute to the implementation of the SDGs, particularly those related to ending hunger and malnutrition (Goal#2).

Indeed, the CFS is the most socially advanced and open platform in the whole UN system and could serve as a role model to implement the other Sustainable Development Goals. But this won’t happen if it is not adequately financed.

This is why the selection of the next CFS Chair was so crucial, and when, on October 15, the CFS selected a delegate from Sudan, this might have looked like a strange choice to an outside observer. Yet the delegate, Amira Dahoud Hassan Gornass, a senior Sudanese woman diplomat with a distinguished career (she is also the Ambassador of Sudan to Italy), was unanimously chosen.

In speeches following her election, it was clear that she enjoyed the support from every regional group, especially Africa and the Near East, but also from the European Union. At least one reason for this broad-based support emerged when, in her acceptance speech, she mentioned she would make every effort to identify a new “financial mechanism” for the CFS.

Whatever Sudan’s political position on other issues, it is clear that here she was elected with the hope that, thanks to her country’s wealthy allies in the Near East, she might be able to help bring a solution to the perennial lack of funds facing the CFS. Let us hope she can.

In the photo: José Graziano da Silva Director General of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and Ambassador Amira Dahoud Hassan Gornass

In the photo: José Graziano da Silva Director General of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and Ambassador Amira Dahoud Hassan Gornass

Cover photo: 2009 World Water Day: Effects of Water Scarcity

Water scarcity can lead to both drought and desertification as well as instigate conflict in communities and between countries. 22 March is World Water Day, a day to focus attention on the importance of fresh water and advocate for the sustainable management of freshwater resources.

Dryland near Manatuto, Timor-Leste. 20 March 2009 – Credit UN Photo/Martine Perret