— Updated on 06 November 2020. —

The magnitude of Arctic sea ice that the Earth has lost in recent decades cannot be recovered. This makes its implications all the more catastrophic – both for the biodiversity of life in these regions and the security of the indigenous communities who call these landscapes their home.

But for a particular few, this irreversible loss of ice brings fresh economic opportunities through the opening up of natural resources and shipping lanes once locked under thick ice. These competing economic interests can heighten geopolitical tensions, putting further pressure on the ecological balance of the Arctic and threatening to destabilise the security of the region.

Shrinking Ice Sheets

The impact of global warming is becoming increasingly noticeable in every habitat across the globe. But for the most Northern and Southern points on Earth, one of the clearest and earliest signs of climate change – melting ice – has been an inescapable reality for decades.

A recent report has now revealed the full extent of this reality: The Earth has lost 28 trillion tonnes of ice between 1994 and 2017.

With the northern hemisphere bearing 60% of the loss, the Arctic has been hit the hardest and remains the most vulnerable to drastic and abrupt change. Within the last year, the region has experienced many landmark events because of this, and they are becoming increasingly common.

On average, the Arctic is currently warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet.

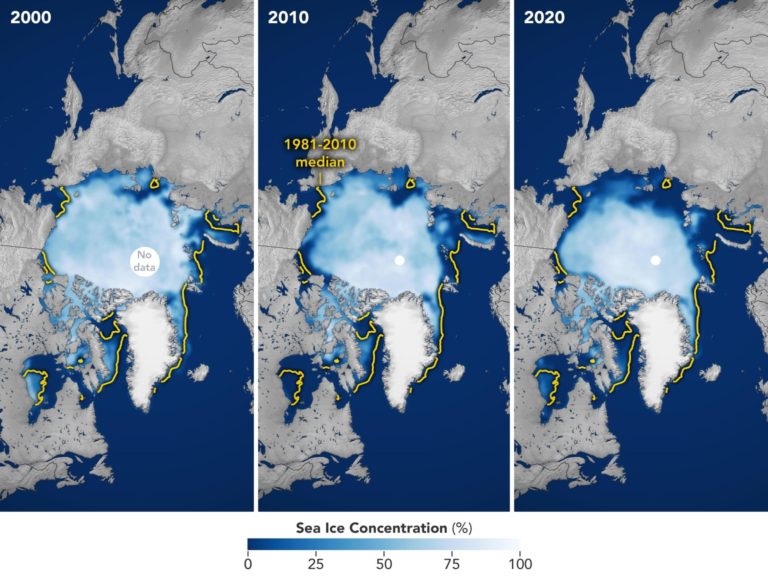

Less sea ice covered the Arctic Ocean this July than in any other July since satellite records began tracking global sea ice extent in 1979. The month also marked the collapse of Canada’s last remaining ice shelf off Ellesmere Island. This September was also the Arctic’s second-lowest sea ice minimum on record. Whilst for the first time since records began, the main nursery of Arctic sea ice in the Laptev Sea has yet to start freezing in late October.

Arctic sea ice cover has always expanded and contracted throughout the seasons. It’s a natural process as the sea surface freezes during the long, dark winter and retreats in the warmer months. But due to global warming, the Arctic’s sea ice extent is now decreasing in all months, accompanied by significant sea ice thinning. Between the winters – October to April – of 1980 and 2019, Arctic sea ice mass has reduced by 230 gigatonnes per year. Unfortunately, the scale of the problem will only increase, as the report found the rate of ice loss each year has been rising steadily.

Related Articles: 5 Visible Signs of Climate Change in Antarctica | Scramble for the Arctic

Another scientific study underlines the severity of the situation, asserting that the Arctic is currently undergoing a period of abrupt change and classifying it as a Dansgaard–Oeschger event (D-O event). D-O events are defined as rapid climate fluctuations – also known as warming episodes – that tend to take place within a matter of decades.

On average, the Arctic is currently warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet, with hotspots in the Eurasian sector of the Arctic Ocean and adjacent land areas, such as the Barents Sea and over Svalbard, experiencing even higher rates. Major sections such as these have warmed by more than one degree Celsius per decade for the last 40 years. Over the past 60,000 years, a temperature increase of this rate and magnitude has only ever occurred during abrupt D-O events.

An increasing number of scientific findings also suggest previous climate models predicting the future trajectory of Arctic warming have seriously underestimated the pace at which sea ice will decline in the coming years.

In one report, the latest version of the UK Hadley Center climate model (HadGEM3) captured key Arctic climate processes that previous models had not been able to take into account. Namely, the pivotal role melt ponds on the surface of ice sheets play in accelerating the rate of ice loss. Because of this, it achieved a 95% match with LIG climate records where previous models had failed.

When run forward in time, the model simulation reached a sea ice-free summer Arctic as quickly as 2035. A drastic reduction from the previously accepted predictions of a sea ice-free summer Arctic by 2048. Adding to the findings, the researchers warn, “once the multiyear sea ice has disappeared in our simulations, it does not return.”

Growing Economic Interests

This would have a devastating ecological impact, but a rapidly shrinking ice sheet also has far-reaching economic implications. In many cases, climate change amplifies existing political and socio-economic challenges regardless of region or climate. However, the harsh landscape and unique geopolitics of the Arctic means that complex security issues are even more closely tied to the region’s climate.

Retreating Arctic sea ice leads to increased accessibility to natural resources and shipping lanes. This brings with it new economic opportunities but at the risk of further endangering the region and its inhabitants. Already, the Trump administration has moved forward with new plans to conduct seismic tests in search of oil reserves in its Arctic refuge.

Increasing tensions between larger heads of states risk reversing the progress of recent decades and push critical environmental issues into the background.

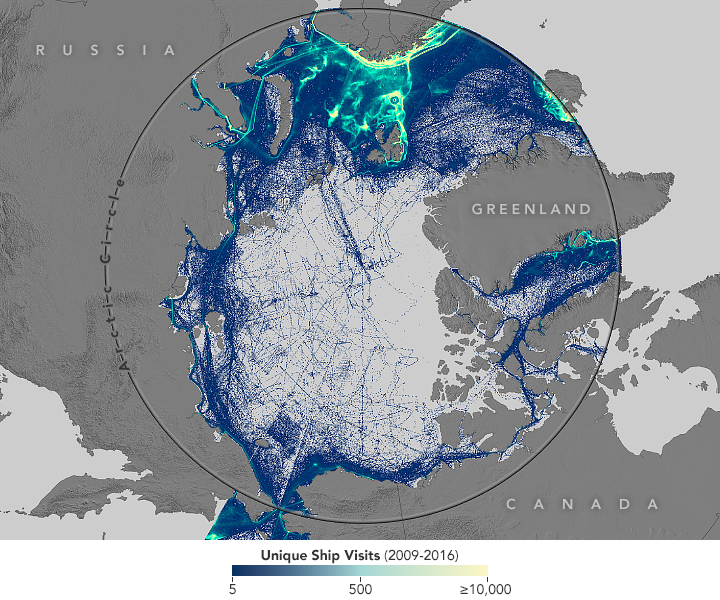

Deep-sea drilling along the Arctic shelf significantly increases the risk of pollution from oil spills, with potentially catastrophic damage to local ecosystems, wildlife and the livelihoods of indigenous communities. Whilst in places like the Bering Sea, where subsistence hunting and fishing is still a vibrant practice, increased shipping would have a lasting effect on the ability of these communities to carry out their crucial traditions.

With the ice melting, routes are becoming more accessible for longer periods of the year. The Northern Sea Route alone reduces travel time and cost between Europe and East Asia by about 40%. If a significantly viable transpolar passage opened up, this journey would be even shorter, shaving off an additional two days of travel.

Already this year, the Northern Sea Route became sea ice-free earlier than ever previously recorded. The first tanker without icebreaker assistance was able to make the crossing in late May, the earliest of any voyage so far. In 2019 the Northern Sea Route was ice-free for roughly two months and saw a shipping increase of almost 60% from the previous year.

The Northwest passage remains less accessible, with ice-free routes only opening briefly during September and still restricted to its narrowest channels. However, it is estimated to become substantially more accessible – for up to two months a year – as soon as 2040. And with the latest reports suggesting current projections have underestimated the pace of current sea ice loss, this could come even sooner.

The increasing viability of this new form of international shipping is also leading to more frequent submissions of territorial claims and territorial disputes between the eight arctic states along with other non-Arctic countries, such as India and China, looking to position themselves for economic involvement.

For India, the opening up of the Arctic ocean’s sea lanes of communications (SLOCs) would reduce the importance of the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). India has already partnered with various Arctic states, including the India-Russia energy partnerships for oil and gas exploration, India-Norway partnership for scientific research and most recently, the India-Sweden partnership for scientific cooperation signed earlier this year.

China’s most recent Arctic Policy Paper asserted its own various rights to “scientific research, navigation, overflight, fishing, laying of submarine cables…resource exploration and exploitation in the area.” The Non-Arctic state has secured several economic, infrastructure, and energy projects in partnership with Russia along the Polar Silk Road. It is also one of the only countries that seem to have considered the eventuality of a viable transpolar passage, referring to it as the “Central Passage” in its Arctic policy.

At the same time, Arctic nations moving to seize sovereignty in the region are also developing their military forces as the growing tensions could lead to possible conflict over exclusive economic zone (EEZ) claims and, in a worst-case scenario, escalate to threats to national sovereignty.

In 2019 the U.S. Department of Defense Arctic Strategy voiced concerns that Russia’s growing military presence could be used to deny access and enforce different interpretations of the right to free passage along the Northern Sea Route. The U.S. interpreted the increasing presence of China and Russia in the Arctic as a threat to their interests in the region and called for increased U.S. naval and icebreaking capabilities in response.

At present, geopolitical tensions remain relatively low due to commitments made by the Arctic Council to keep the region a conflict-free zone, with lasting cooperation based on mutual interests and agreements. This unique status is commonly referred to as “Arctic exceptionalism.” But a shifting geopolitical climate could still disrupt this long-standing cooperation.

Increasing tensions between larger heads of states risk reversing the progress of recent decades and push critical environmental issues into the background. Indigenous peoples are already excluded from military security discussions within their states, making the likelihood of exclusion from similar discussions at intergovernmental forums high.

Yet, indigenous communities are proven to be most at risk from climate change whilst also possessing the wealth of environmental knowledge to play a key role in its mitigation. If the Arctic is to avoid the ecological disaster it is currently heading toward, the voices of both climate scientists and indigenous people need to be prioritised over the competing economic interests of global leaders.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Declining Arctic sea ice. Featured Photo Credit: Annie Sprat / Unsplash