I’ve always been slightly sceptical of those arguing for social entrepreneurship as a force for good. I’d grown up with the conception of the state provisioning services to those in need. Charities step-in when necessary to fill omissions by the state, and the private sector tended to offer limited philanthropic support from a distance. I had limited knowledge of the social entrepreneurship sector and failed to see where it would fit in with my tri-configuration.

Hoping to get answers I sat down with Charlie Fraser, director and co-founder of TERN, The Entrepreneurial Refugee Network. From the lead-off Charlie began to lay out a new perspective. In response to my innocuous question about what motivated TERN, he started to explain that refugees hold a critically unique place in contemporary British society, sat “at the heart of” its most dividing social issues, which went unstated but were unambiguously clear: inclusiveness and austerity.

Taking me back in time, Charlie described how before this broad vision and before TERN there was simply the problem of marginalization. He outlined how “by any marginalization standard in the U.K., refugees will be in the top three and frequently the top one percent.” Going further, this marginalization was not only ethically problematic but also was an economic anomaly. The skillsets refugees possess should mean they are sought by the labour market—not excluded from it. However, the structural failures of resettlement efforts caused by austerity have restricted refugees from entering the job market, and the social interactions it brings, consequently excluding them from mainstream society. Thus, as Charlie concludes, the economic restrictions of austerity on refugees had to be challenged for the social issue of integration to be treated.

In came a group of millennials who had all previously worked with refugees in different capacities, suddenly aware that their privileged access to the labour market could be transferred to others. Charlie argued that this group of students and recent graduates had everything that refugees lacked, “access to networks, access to finance, and … power.” By offering these same advantages to refugees, they could integrate them into the area on which society places the greatest sense of value, business. Thus, in 2016 The Entrepreneurial Refugee Network was born, a social enterprise that continues to this day to improve refugee inclusion into UK society via economic support and empowerment.

In the Photo: TERN logo. Photo Credit: TERN

What came through to me here was not only an efficient business model but also a clear sense of social responsibility being an economic driver. Paraphrasing Charlie, his personal sense of duty fit into a much broader pattern among businesses of the need to act responsibly, driven by the desires of millenials. The relative fickleness of millenials in everything from what they buy and where they work to who they date has led to more companies marketing themselves as a socially beneficial force to potential buyers or employees.

TERN has tapped into this trend. It has leveraged corporations’ desire for a socially responsible image by creating partnerships with them and getting business support in return. Its success in using this business ethic to drive its development is evidenced by its largely millennial generation staff and partnerships with Ben and Jerry’s, Oliver Wyman, and O2.

What really makes TERN a good representation of thought-out social entrepreneurship is how it applies the logic of creating a social force for good to not only its business model but also its ethic in working with refugees. Both its model and emphasis place it between the traditional corporate, civic, and charity sectors. In explaining this, Charlie states that the dual issues of inclusion and austerity are issues that touch on all three of these sectors and so TERN must do the same.

Whilst acknowledging the need for government to renew its assistance to refugees, TERN’s decision to involve the private sector into a traditionally civil society issue articulates refugee exclusion as not a “minority” or “charity” problem; it is one that bridges all elements of society and thus affects us all.

This innovative approach to refugees seeks to integrate them into society through their economic value, not simply through state aid and their consumption, but through their own entrepreneurship. This approach is both moral, novel in a Western context, and also economically smart, tapping into the underutilized potential of refugees for the British economy.

A report by the Center For Entrepreneurs (CFE), on the subject titled “Starting Afresh” came out in March of this year and offers clear arguments for refugee entrepreneurship. The report claims that “sponsoring interested refugees through a programme for just £2,000 each (totalling £4.8 million) could lead to savings of £170 million over five years—almost 10 percent of the forecasted resettlement cost and a 35x return on investment.”

In the Photo: In 2015, then Prime Minister David Cameron pledged to resettle 20,000 Syrian refugees in the UK by 2020. Currently, the present government is on track with its target. The Centre has sought to calculate the potential public savings and benefits if a refugee entrepreneurship programme (REP) were made available to all interested refugees from Syria. Photo Credit: CFE

Charlie explained that around half of the ninety refugees they work with have actually launched businesses in their home countries and about 15 percent in the UK, but that’s not what excited him the most about TERN’s work.

“We started as a social enterprise, not a charity primarily because we wanted to say that refugees aren’t a humanitarian cause. This is not a charitable issue. This is an economic and social issue. And we have to start phrasing it like that otherwise we’re going to lose it.”

—Charlie Fraser, TERN co-founder and director

What quickly becomes clear is that TERN’s current work and future aims stretch far beyond the 90 refugees it currently works with directly. Refugees who can start businesses demonstrate their own economic and social value as they pay taxes, create jobs, and support their local communities. TERN’s aim is to try and support refugees in changing the tropes that are endowed upon them, hopefully creating a more positive environment for refugees and their neighbors to live amongst each other.

In the Photo: Syrian boy Alan Kurdi found dead on the shore of Bodrum, Turkey, after he drowned attempting to sail to Greece. Photo Credit: Nilufer Demir/DHA

Exclaiming that “if people aren’t going to be convinced by humanitarian needs after Alan Kurdi,” the Syrian boy found drowned by a Turkish soldier on a beach, Charlie stated “we need social and economic arguments as well.” Viewing refugees, not as charity, but as individuals who can be empowered to benefit themselves and others reverses “the trends that become stereotypes” of refugees as a social and economic burden. It also tactfully avoids the accusation that refugees are living solely off state welfare or that they drive down wages and take native workers’ jobs.

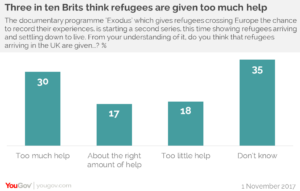

In the Photo: A Bar chart portraying the results of a YouGov poll asking British people for their opinion on how much they are helping refugees. Photo Credit: YouGov

Public opinion suggests that this is a necessary argument to make as a YouGov poll from June indicated that 30 percent of the British people asked believe refugees are getting too much help and only 18 percent too little, with 17 percent saying it’s the right amount. Clearly, there is little public pressure on the state to increase funding for refugee integration even despite the ongoing humanitarian crisis in the Middle East and the relative deprivation levels of refugees in the UK.

There is also a less-well cited logic for avoiding the humanitarian argument. International Humanitarian law dictated in the 1951 UNHCR Refugee Convention states that recognized refugees have a right to “non-refoulement,” which means they cannot be returned if they face threat to their life or their rights. This applies to many refugees who have fled violence, and thus the UK government is legally, not morally, obligated to accept refugees and ensure their human rights are maintained.

The argument Charlie cites as the most pertinent however is that “states around the developed world do not have the financial capabilities they used to or are already maxed out where they can deliver.” Supporting the point made in the polling above, individuals’ appetite for themselves or their government’s to provide humanitarian contributions are low.

In the Photo: 20 Main Contributors of humanitarian assistance in 2017, according to Development Initiatives’ 2018 Global Humanitarian Assistance Report. Photo Credit: Development Initiatives

Whilst global trends may contradict this, according to Development Initiatives’ 2018 Global Humanitarian Assistance Report, in the UK “the refugee support network is in a bad way.” The government’s termination of the Refugee Integration and Employment Service (RIES) in 2011 was followed by the axing of the Ministerial post for Syrian Refugees in 2016, and the new Integrated Communities Strategy fails to offer any innovation in terms of methods.

According to the previously cited CFE report, “only two out of every five” refugees find employment. And, of those, “half struggle to find employment appropriate to their skill level.” The report concludes that more government aid is needed for refugee support, but Charlie argues that organizations should instead look towards the private sector.

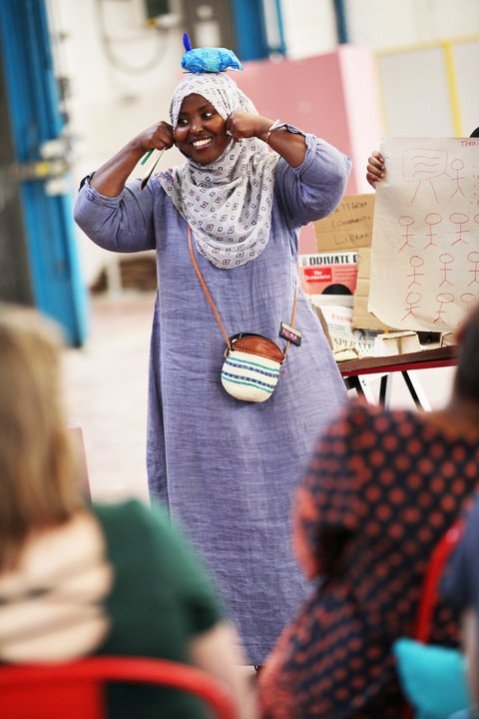

In the Photo Gallery: Personality and Cognitive Traits common among refugees, according to CFE’s Report titled “Starting Afresh”. Photo Gallery Credit: CFE

“We’ve come a long way through state led development. The next leap has to come from additional capital sources and unless you want a revolution then social capitalism has to come to the fore,” Charlie says. He articulated this as meaning the incentivization of the private sector to offer more than charitable giving, away days, and a values page, but to have an actionable plan for sustainable social change.

Whilst cynics may call this utopian, Charlie maintains that “The exciting thing is it’s being led by our generation.” That millennials are demanding employers to hold these values or face rejection from potential applicants in favor of organizations with a stronger social vision of change. Thereby it’s becoming a business argument, not simply a social or moral argument, “which is what’s powerful.”

This change in perspectives from previous generations to millennials seems to be borne out by research from 2015 carried out by consultancy company, Global Tolerance. The survey of over 2,000 people in the UK found that 44 percent found meaningful and altruistic work was more important than a high salary and 36 percent would work harder if their company bettered society.

However, the evidence for businesses offering more than lip-service or marketing campaigns in response to these demands is limited. It is also not yet clear whether millennials are actually more attuned to their hearts rather than their bank statements.

Nonetheless, it may still be an important trend for those interested in Corporate Social Responsibility to follow as Charlie indicates a growing number of startups in his field taking a similar approach. Maybe as a response to trying to attract millenials into this arena Charlie states that new organizations and people looking to make a social impact are saying:

Let’s not make this a really dry space where you are trying to deliver on grant dictated terms but actually let’s send this into a space that has all the energy, has all the excitement of the startup world, and a lot of the tech world and bring it into refugee space.

Whilst comprehensive data supporting this argument is hard to come by, Charlie states that at least in the refugee entrepreneurship sector this argument has won out, pointing to a summit that will be held in London later this year by the CER bringing together similar groups to TERN from as far away as Australia.

With pride in his voice Charlie proposed how this summit would cap a brilliant year for TERN as their program has expanded from London to working with a similar partner organization in Germany. And whilst the problems remain many and vast there remains a sense of optimism among those working on this issue, according to Charlie. After laying out all of this, the final words I am left with is “This is exciting.”