This article was originally published by Development Alternatives Blog Series — Alternative Perspectives. The original article can be found here.

A popular TED talk by the founder and promoter of the Social Progress Index, describes the potential for achieving the very ambitious and complex set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals laid out in the 2030 Global Sustainable Development Agenda within the desired 15 years. And that, without increasing “GDP growth.” The Social Progress Index is just one of many “development indices” that have been designed in response to a growing disenchantment with “economic growth” as the one and only indicator and measure of “development” of a society or country. Communities, think-tanks, and even governments (some of them) across the world are questioning whether economic growth can indeed be the aim and hallmark of a developed society in the same manner as human well-being and environmental quality are.

[W]hen economic growth becomes the primary aim of development, with GDP as its measure, both human well-being (especially in an equitable manner) and ecosystem health suffer.

Unlike the measurement of social, cultural, human capacity development, and eco-system health, economic development (as an outcome of economic growth) has been reduced to a measurement in simplistic quantitative terms resulting from production and service transactions — the GDP (the more the better). This has made it an easy and therefore a popular indicator of “overall development.” In fact, attempts to value other development parameters have often been in economic value terms as well. Yet we know that when economic growth becomes the primary aim of development, with GDP as its measure, both human well-being (especially in an equitable manner) and ecosystem health suffer.

The emerging view is that economic activity reflects the interaction of people with each other and with their natural environment, resulting in positive or negative social and environmental outcomes. It is therefore necessary to guide, regulate, and govern this activity such that the key objective — that of just, equitable, and sustainable development for all, now and in the future, is achieved. The “growth” paradigm that continues to dominate the design of our economies holds that there is adequate ecological capacity to fulfil the demands of the 7 billion tending towards 10 billion people in this world and that technology will be the panacea required for a comfortable existence. This paradigm is now passé. A variety of different approaches now exist.

The green growth approach looks at dynamic economic development as the fuel for societies to thrive, but demands that this development be within ecological limits. It states that a country can increase its GDP by exploiting natural capital, but overuse of those resources will reduce national wealth. Natural capital accounting enables smarter planning and decision-making, and in many cases, countries choosing to conserve natural capital instead of further exploitation. According to this approach, all countries, rich and poor, have opportunities to make their growth greener and more inclusive through strategies that reflect local contexts and preferences. A critique of this approach is its focus on continued economic growth (GDP) and smarter technological or market methods to “green” this growth. Critics also point out that ascribing monetary value to natural capital makes it a tradable commodity that can be “exploited or conserved if paid for.” Payment for ecosystem conservation would lead to limiting the access of natural resources and therefore to growth opportunities to some (mostly the less powerful). It has also been criticised for not addressing current consumptive lifestyles of the richer nations.

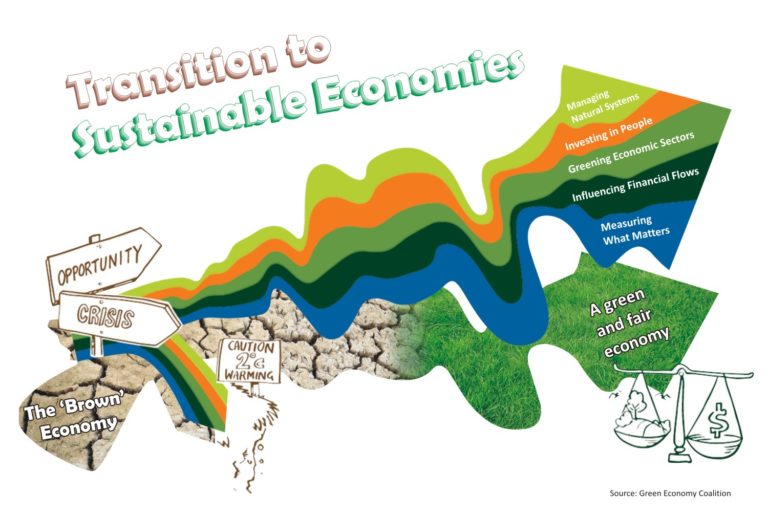

The green economy (as opposed to green growth) approach has been defined as “one that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. It is low carbon, resource efficient, and socially inclusive.” The basic premise of green economy is that there is a way to eradicate poverty and foster sustainable development without harming the environment. The strategies for transforming economic processes into green and inclusive ones require understanding the social and ecological outcomes that must be measured and tracked; greening the current brown production and service sectors through technology and institutional measures; investing in natural systems and human capacity development (especially with a focus of equity of opportunity); and devising financial flows and market structures that facilitate this shift.

The blue economy (not to be confused with marine economy) is yet another approach. It argues that it is possible to move from scarcity to abundance through systemic design based on the laws of nature by linking different productive processes, in fact creating new productive processes, using local resources and labour. There are no wastes in a blue economy conceptualisation, and multiple benefit streams add value to local economies resulting in greater human prosperity. Although this view does not directly address inequities and distributional injustice within capitalist market systems, it relies on localisation of interventions for system correction and robustness.

Another perspective is that of the circular economy, which promotes a systemic view of the resource use within production processes. It looks at “closing resource loops” to maximise service value generated per unit of resource used, with subsequent recovery and regeneration of products and materials at the end of service life. This is an alternative to the linear (make-use-dispose) economic growth perspective. This too relies on the technological and business model re-engineering and bases the shifts in consumptive patterns as driven by shifts in production systems. A circular economy model need not be very localised or decentralised, and it breaks sectoral silos to focus on efficiency of resource use and reduces wastes, but does not address social equities.

While there are some subtle and some significant differences in the approaches outlined above, what is common is that each looks at economic processes as the means to achieve human prosperity and environmental health and not as an end in itself.

Editor’s Picks – Related Articles:

“Indigenous Peoples and the UN Sustainable Development Goals”

“Indigenous Peoples and the UN Sustainable Development Goals”

“Can Sciences-based Targets Truly Guide Sustainable Development?”

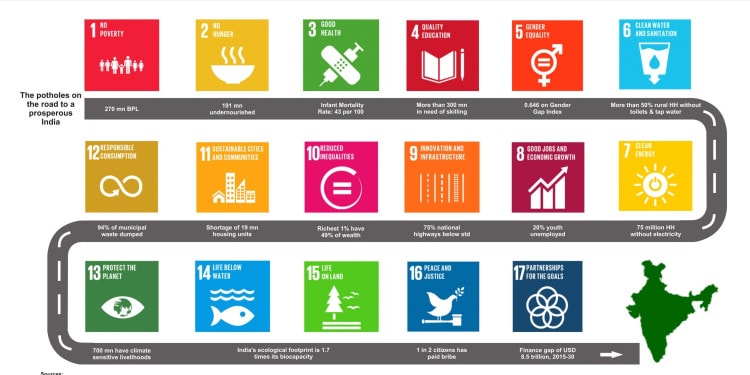

What does this mean for India? A country where 1% of the population controls over 73% of its total wealth; where over 270 million still live in absolute poverty without access to opportunities that would pull (at least) their next generation out of the abyss. Where 65% of population is below 35 years of age — a majority of whom are neither skilled nor employable in the current industrial-market economy. Where on one hand, there is an exodus to non-farm jobs and desperate urban living, and on the other, exists a significant majority that continues to directly depend on natural biotic resources for their livelihoods, threatened by social, political, and market forces besides climate change. We are a country of contrasts — not all desirable; our economic growth trajectory seen concurrently with our human development track record and state of the environment leaves much to be desired. Some say that we are in many ways headed for the precipice and the elephant may already be too heavy to turn around.

We now have a historic opportunity to address this concern. With the framework for the 2030 Global Agenda for Sustainable Development as a guide, the country is set to design a 15 year National Development Plan that could turn the juggernaut from a path of sure shot disaster to that of sustainable development. Needless to say, the vehicle — our economy — will need serious redesign. Whatever be the kind of approach — new or a combination of the varieties of economic approaches possible — that India adopts, one aspect is clear. The Indian approach, rooted in realities of this complex country, will need to be based on key fundamentals that put both people and environment at the centre of its formulation. It will need to be based on the five principles of: system integrity across sectors and resource flows that impact communities and their environment; efficiency and maximisation of service from resources with a zero waste credo; harmony and balance of natural systems with human needs; sufficiency determinants of resource consumption per capita; and most importantly, universality that ensures equity of opportunity and social justice. These principles and resultant tangible metrics will need to guide the evolution of new business models, technology applications, fiscal systems, and market regulations. Such a blueprint will help us track progress of and achieve genuine sustainable development for all.