After the November 13th terrorist attacks in Paris, in which 130 people were killed, sending shock waves across the European continent, Europe is where America was after 9/11. The question immediately arises, will Europe be tempted to follow in the footsteps of America and increase government surveillance at the expense of civil liberties?

Across the Atlantic, many analysts and journalists were quick to make comparisons to the 9/11 terrorist attacks from a decade earlier. As the world mourned, European governments began developing security policies that aimed to prevent another terrorist attack from happening again. Read all the information you need on cyber security on Glasswall Solutions website and avoid threats.

French President Francois Hollande immediately extended the country’s state of emergency for three months, and shortly after, French security forces set its cross hairs on ISIS, which had claimed responsibility for the Paris attacks. While French intelligence forces were quick to identify and track down the suspects of the attacks, the question then turned to how the French and European governments would stop ISIS on a more elusive front: the world wide web.

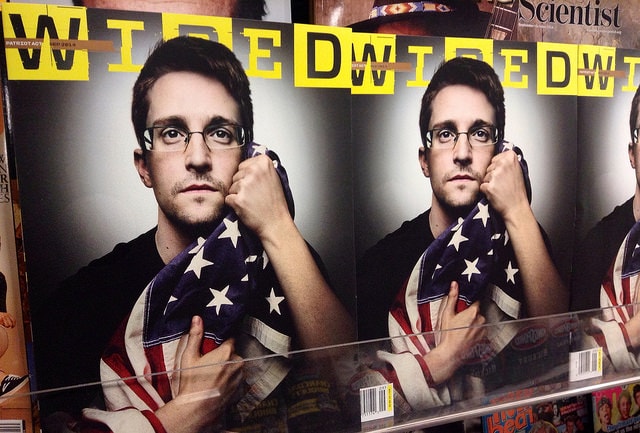

Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the American government overwhelmingly passed the Patriot Act. Within the bill, certain provisions allowed for government surveillance agencies to oversee electronic communications, including phone records. After government whistle blower Edward Snowden revealed the NSA’s mass-data collection program in 2013, many government surveillance programs came under public criticism and were later reined in.

Although some right-wing factions are calling for a European Patriot act in the wake of the Paris attacks, most Europeans remain skeptical, if not concerned, about European governments and the EU installing broad electronic surveillance measures. Privacy advocates are voicing the most concern, as countries such as the United Kingdom are pressing for greater access to its citizens’ internet activity and encrypted conversations.

While the debate on internet surveillance is likely to continue well into 2016, there are several areas where European regulation can be expected to develop.

EU Passenger Name Record

In October, the European Parliament and council negotiators reached an agreement that would allow for the creation of a Passenger Name Record (PNR) database. The directive will regulate PNR information for the “prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution of terrorist offences and serious crime,” according to a European Parliament press release. The draft will be sent for final approval in 2016.

The directive allows for air carriers to transfer Passenger Information Units of PNR data to EU member states. As it stands, the directive only applies to flights entering or exiting the Eurozone. Air carriers are not obliged to release PNR for intra-EU flights.

Many privacy advocacy groups decried the new directive as being unnecessary and ineffective at preventing terrorism, but at the European Parliament, the reaction was different: the Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Committee approved the measure 38 votes to 18.

In the Photo: The European Parliament will vote on its PNR directive next year. Photo: niksnut/Flickr.

In many of the recent terrorist attacks, the terrorists had already been flagged as “people who needed further tracking,” the Brussels-based advocacy group European Digital Rights noted on its website. “The attackers from the last terrorist incident in Paris were already known to French authorities and details of their travels were also known. An EU PNR Directive would not have brought any more security, only more risks.”

Related Articles: “THE PARIS ATTACKS: WHAT THEY REALLY MEAN” by MICHELE SCIURBA

“THE KEY FOR PEACE: THE INDISPENSABLE ROLE OF THE UNITED NATIONS”

Data Sharing Between European Agencies

Within the EU, conservative lawmakers are advocating for European security and intelligence agencies to be more transparent with their information.

For some, sharing information on suspected terrorists and potential terrorist plots may seem like a no-brainer, whereas others argue that these security hawks are merely compensating for their own country’s intelligence shortcomings.

In the photo: Edward Snowden helped reveal the NSA’s bulk-data collection of American phone records in 2013. Photo: Mike Mozart via Flickr.

Sophie in ‘t Veld, a reporter for ALDE, described French and Belgian transparency proposals as a “smokescreen,” for their own security failures. “It is so sexy setting up big IT systems,” ‘t Veld told Politico. “Whereas what we really need is human intelligence, people on the ground who know the people in the community.”

How surveillance information is to be shared among EU states and what type information would be accessed (personal, commercial, etc.) is likely to be the subject of much debate in the coming months.

De-Radicalize the Internet

From the Paris attacks to the San Bernardino shootings in California earlier this month, ISIS and other Islamic extremists have used the internet and social media to gain access to radical Islamist platforms. In response, some European governments have pressured Facebook, Twitter and other social media platforms to ban hate speech and restrict ISIS propaganda.

Following the Charlie Hebdo attacks last February, the French government was able to pass a bill that forced Internet service providers to install tools that allowed security agencies to search for patterns of radicalization in real time. The tools that the ISPs were forced to install when browsing deeper into the web were mostly different VPNs. And if you were to read their express vpn review, you’d know that’s one powerful cloaking software. In Germany, Facebook’s regional manager is under investigation for the site’s alleged failure to remove anti-immigration posts. Furthermore, the EU proposed a non-binding resolution earlier this month that would allow for criminal charges to be placed on Internet service providers that don’t aid governments in removing extremist content.

Privacy and free-speech advocates, such as European Digital Rights, have criticized such proposals and measures as being too broad. Some of these groups argue that such vague legislation could have significant unintended consequences.

In the photo: A makeshift memorial outside the Bataclan concert hall, Paris. Photo: Takver via Flickr

All this stuff is supposed to bring about some sort of utopian version of the future or bring about dramatic changes in the future as well,

UCLA History Professor James Gelvin told an audience at a panel discussion on the Paris attacks. “I don’t see it actually as that. Social media does not make somebody who watches it decide ‘I’m going to join ISIS.’ It shows them what ISIS is all about, it gets the word out and that in itself is important, but overall there has to be that motivation for that person to see that message and say, ‘This is for me and this is what I want to do.’”

In either case, many extremists or terrorists could simply “go dark” and turn to encrypted Internet services to communicate and coordinate attacks.

Getting Around Encryption

One large roadblock that prevents European security agencies from accessing information is encryption.

Most internet users are familiar with encryption, such as setting passwords or chatting through Facebook’s WhatsApp that protect their information and conversations from hackers, creeps and governments. For years, European governments have been battling companies for access to their encrypted services, igniting a debate between a citizen’s right to privacy, corporate responsibility to its users and national security.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron and CIA Director John Brennan are long-standing critics of encryption services and have repeatedly demanded that tech services allow access to encrypted content or weaken its security overall. As part of its prolonged state of emergency, France expanded its enforcement of Internet access, including the ability to remove illegal content.

A recent article in The Economist highlighted four methods that European governments might use to access encrypted content:

- Governments should be given codes that would allow agencies to crack into encrypted data;

- Tech companies would be forced to crack into encrypted content when the government issues a warrant;

- A ban on encrypted services and apps that cannot be cracked;

- Tech companies must sell encryption devices and services that have weakness built into them, allowing government access.

So far, tech companies have resisted calls for government access to encrypted data by arguing that privacy and personal protection are necessary for internet users. Some Internet users that fear government intrusion have already started using encryption services that are outside the jurisdiction of their governments. The Swiss encryption service Protonmail allows users to communicate via e-mail without its users fearing that their e-mails will be permanently stored in a database or having their encryption keys copied.

The Information Technology Industry Council (ITIC), an American advocacy group representing Apple, Microsoft and other tech giants, argues that “weakening security with the aim of advancing security simply does not make sense.” The ITIC warned that weakening encryption would weaken the banking system, electrical grid and aid cyber criminals.