2021 was a special year for One Health, the year in which it turned global and became a public health priority policy across the world. The first seismic shift came at the G7 meeting of Ministers of Health, prior to the formal Heads of State gathering in Carbis Bay and it turned up in the final G7 Summit communiqué on June 13, 2021, with a specific reference to it as a major principle to help fight the current Covid and future pandemics:

“Improving integration, by strengthening a “One Health” approach across all aspects of pandemic prevention and preparedness, recognizing the critical links between human and animal health and the environment…”

The G7 meeting was followed by the G-20 meeting in October 2021, itself preceded by a preparatory ministerial meeting on health issues in September. Again, One Health took center stage with a groundbreaking Declaration of the G20 Ministers of Health, clarifying that:

“…linkages between human and animal health, the effects across One Health-related to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), food systems, and environmental health, including climate change, ecosystem degradation, increased encroachment into natural systems and loss of biodiversity should be addressed through the One Health approach, leveraging and relying upon the technical leadership and coordinating role of the WHO, FAO, OIE and UNEP.”

The G20 Finance Ministers echoed the priority given to One Health in their own declaration calling for appropriate funding, noting that “Greater and more predictable funding is necessary for the WHO to perform its critical functions and ensure that there are no gaps in the surveillance-to-action loop, and to strengthen the integrated One Health approach.”

On October 29, the G20 Health and Finance Ministers in a joint communiqué announced the establishment of a Joint Finance-Health Task Force in line with One Health principle and declared:

“We are determined to advance pandemic, prevention, preparedness and response, as well as to prepare the way for stronger post-pandemic recovery, in line with the comprehensive One Health approach, taking into account work of the Tripartite and UN Environment Programme and their newly established One Health High-Level Expert Panel, and with previous G20 commitments to tackle antimicrobial resistance.” (bold font added)

This was the culmination of years of committed effort, in particular in the One Health area. It has meant the active engagement of physicians, veterinarians, advocates, institutional organizations such as UN agencies like WHO, and the International Organization of Animal Health (OIE), expert bodies such as The Lancet One Health Commission, earlier G7 and G20 preparatory meetings in Italy, a World Health Summit in Berlin, and a host of academic, non-profit, video conferences, other events and articles.

Meanwhile WHO did not stand by idle as its Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and his secretariat prepared the special session of the World Health Assembly (WHA) from November 29 to December 1, calling for One Health as a guiding principle to reform global public health. The session resulted in the unanimous adoption of One Health by the WHA, launching the process to develop a historic global accord on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

The United Nations special agencies mandated to address health issues were quick to react and manifest their support.

On December 1, 2021, in a joint press release, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that they “welcome[ing] the newly formed operational definition of One Health from their advisory panel, the One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP), whose members represent a broad range of disciplines in science and policy-related sectors relevant to One Health from around the world.” And they added that their “four organizations are working together to mainstream One Health so that they are better prepared to prevent, predict, detect, and respond to global health threats and promote sustainable development.”

A visionary unanimous worldwide institutionalization of One Health is the goal as cogently discussed in many Impakter articles. The objective is to significantly “help protect and/or save untold millions of lives in our generation and for those to come.” An ambitious objective, to be sure, but feasible because of the novelty of the concept that calls on traditional medicine to look beyond the boundaries of human health.

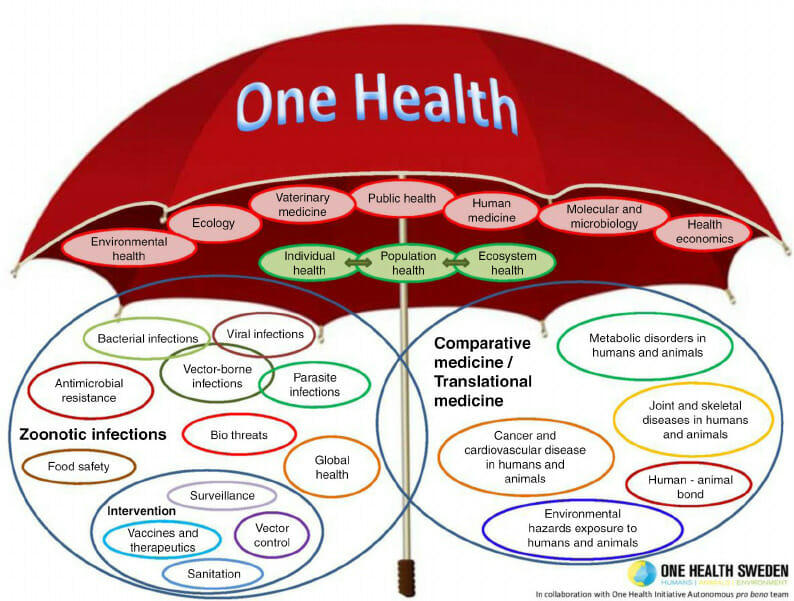

Perhaps the single graphic that best expresses what One Health is all about was created in December 2013 and early 2014 by ONE HEALTH SWEDEN in collaboration with the One Health Initiative Autonomous pro bono team*:

Concise definitions vary, nonetheless: One Health is the collaborative efforts of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally, and globally to attain optimal health for people, animals, plants and our environment.

Moreover, One Health involves collaborative, multisectoral, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary communication tactics and strategies that function at the local, regional, national, and global levels. Engagement dictates that in order to achieve optimal health outcomes there must be recognition of the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment.

Public health epidemiology and clinical research (i.e., comparative medicine/translational research) are evidence-based and committed to preventing disease and improving health care for all.

The politics of a One Health approach relative to how public policy decisions are made by elected officials are being explored but are still evolving. Elected officials write laws, regulations, and determine how public resources are allocated.

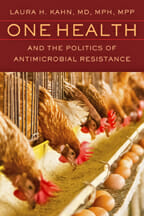

However, material interests, political ideology and culture play major roles in ultimate implementation. Indeed, the book, One Health and the Politics of Antimicrobial Resistance by Laura H. Kahn, MD, MPH, MPP comprehensively investigated controversial issues involved “in a unique way while offering policy recommendations that all sides can accept.”

Dr. Kahn analyzed the surprising outcomes of differing policy approaches to antibiotic resistance around the globe, focusing on the surge in antimicrobial resistance in food animals and humans from a One Health perspective. Although the medical community has blamed the problem on agricultural practices, the agricultural community insists that antibiotic resistance is the result of the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in human medicine. Dr. Kahn argues that this blame game has fueled the politics of antibiotic resistance and hindered the development of effective policies to address the worsening crisis.

Dr. Kahn analyzed the surprising outcomes of differing policy approaches to antibiotic resistance around the globe, focusing on the surge in antimicrobial resistance in food animals and humans from a One Health perspective. Although the medical community has blamed the problem on agricultural practices, the agricultural community insists that antibiotic resistance is the result of the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in human medicine. Dr. Kahn argues that this blame game has fueled the politics of antibiotic resistance and hindered the development of effective policies to address the worsening crisis.

A thoughtful recently published article entitled “Meaning and mechanisms of One Health partnerships: insights from a critical review of literature on cross-government collaborations” offers another valuable academic perspective, analyzing 58 articles published from 1967 to 2018 from the fields of global health, infectious diseases, management, nutrition and sustainability sciences.

The analysis revealed that multisector partnerships assume a variety of forms and emerge in conditions of dynamic uncertainty and sector failure when the information and resources required are beyond the capacities of any individual sector. Such partnerships are inherently political in nature and subsume multiple competing agendas of collaborating actors. The authors of the article concluded that “Sustaining collaborations over a long period of time will require collaborative approaches like One Health to accommodate competing political perspectives and include flexibility to allow multisector partnerships to respond to changing external dynamics.”

A Historical Perspective: How and who was behind the birth of the One Health concept

Retrospectively, the first element to grasp and appreciate is found in this article entitled, A perspective … some significant Historic Inspirations for advancing the One Medicine/One Health concept & movement – 19th, 20th and 21st Centuries. This provides a prospective, insightful enlightenment for an elementary understanding as envisioned by leading health science minds of the past. The concept is not complicated; it is relatively straightforward, palpable and highly efficacious.

The foundational 20th Century piece of literature that provides both a basic understanding and underpins the One Health concept may be found in the writings of James H. Steele, DVM, MPH, and Calvin Schwabe, DVM, DSc. They persuasively expounded in depth upon the issue(s) of One Health.

Dr. Steele, the veterinarian who started the veterinary division of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta in 1945, is universally considered the doyen of veterinary public health and dubbed “father of veterinary public health”. But he is more than that – when it comes to One Health, he was the one who developed the concept. He was actually heard to use the term “One Health” during the late 20th century, the time when the idea, indeed, a new philosophical approach to medicine took shape.

While no specific references of Steele’s usage of the phrase have been identified or located in his many late 20th century public lectures or publications, the phrase “One World, One Medicine, One Health” was first expressed verbatim to the first co-author (Dr. Bruce Kaplan) via telephone comments sometime in 1996-97. Steele had called the co-author at his Washington, DC office while working for the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), Office of Public Health and Science (OPHS). At least one other One Health colleague-leader, William Stokes, DVM, a distinguished member of the American Veterinary Medical Association’s (AVMA) One Health Task Force has concurred via email with a similar recollection of him using those words in the Spring of 2003. Steele repeated this phrase again in 2007 at a private dinner in the Army-Navy Club, Washington, DC.

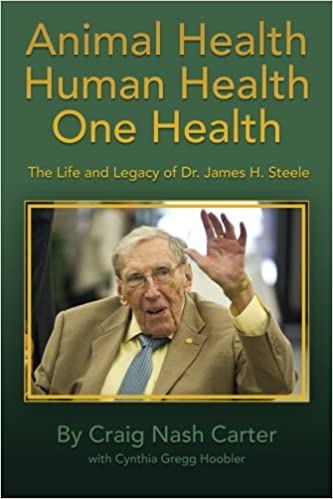

Steele routinely telephoned the first co-author once each month during the last 15-16 years of his life until his death in 2013 to discuss One Health, public health and other pertinent issues. The second co-author, Dr. Craig N. Carter, is the official Steele biographer and after conducting 20 years of research, in 2015, he published a book entitled Animal Health, Human Health, One Health: the Life and Legacy of Dr. James H. Steele (2 editions).

There were two turning points in the emergence of One Health. The first, and one that Steele immediately recognized as a guiding force, was the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA)’s 2006-7 special report written by Lonnie King, DVM, MS, MPA, DACVPM Chair of the One Health Initiative Task Force (OHITF) with its distinguished participants. The report shone a worldwide spotlight upon One Medicine/One Health principles, as did the next AVMA Task Force Report in 2008.

The second turning point came for Steele, again in 2007, when the American Medical Association’s (AMA) landmark “One Health” resolution was adopted – the following photograph reflects the happy mood as the two associations decided to work together:

The historic “One Health” liaison between AVMA and AMA in effect today was fostered by collaboration between Drs. Mahr and Davis.

In addition, there were publications that helped spread the new concept in the medical community and beyond. In particular, Dr. Schwabe’s powerful two books, “Veterinary Medicine and Human Health” (3 editions: 1964, 1969, 1984) and “Cattle, Priests and Progress in Medicine” served as resources with references for generations of medical professionals and are still today the most powerful documented predecessors to current dissertations.

Without a doubt, Schwabe coined the “One Medicine” moniker.

If one carefully reads the voluminous comments written and publicly spoken by Steele and Schwabe it becomes clear that nearly all aspects of the One Health concept/approach were addressed by them in one way or another. All subsequent expanding/mounting One Health historical data to date obviously sprang from these two extraordinary, brilliant intellectual global public health leaders.

Steele was among the first to recognize Schwabe’s landmark ‘One Medicine’ public health book observations and conclusions.

The scientific world relies heavily on a variety of current ongoing published journal articles to substantiate and pursue continuing validity and updating for major systematic, methodical, and technical paradigms such as “One Health”. Two early heterogenous 21st century publications that included eclectic individual articles illuminating the wide-ranging nature of the concept were Veterinaria Italiana 45-1 January-March 2009 (izs.it) and Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Journal’s One Health: The Intersection of Humans, Animals, and the Environment.

Arguably, the earliest landmark One Health textbook was Human-Animal Medicine: Clinical Approaches to Zoonoses, Toxicants and Other Shared Health Risks. Subsequently, excellent books have been written. Regrettably, many of the major contributor examples and some other leaders of the One Health movement have been overlooked and/or are not generally known about by One Health newcomer advocates.

Ironically, this simple, obviously effective approach that has resulted in more expeditious and efficacious public health and clinical health research for decades — even for centuries — has only begun to be recognized and pushed hard as the “way to go” during the early decades of the 21st century.

Looking forward

As we saw, 2021 was a big step forward for One Health as it was adopted in the international community as a major guiding principle for global public health. In particular, major international health organizations joined to recognize and utilize One Health principles with the new FAO-OIE-UNEP-WHO platform to tackle human, animal and environmental health challenges. While prospects are good for near future implementation worldwide, that goal has yet to be achieved.

Unfortunately, it appears to have taken the tragic emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic to fast-forward recognition and give widespread impetus towards One Health implementation.

Spanish philosopher George Santayana is credited with the aphorism, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”.

And British statesman Winston S. Churchill wrote, “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

————————————————————————————————————–

For further comprehensive documentation on ONE HEALTH:

- https://www.onehealthinitiative.com ù

- www.archive.onehealthinitiative.com

- https://www.onehealthcommission.org/

- SAVING LIVES BY TAKING A ONE HEALTH APPROACH

*The One Health Initiative Autonomous pro bono Team includes the authors of this article, Bruce Kaplan, DVM and Craig N. Carter, DVM, PhD as well as Laura H. Kahn, MD, MPH, MPP

**Deceased November 6, 2020

Article Contributor: Claude Forthomme, Senior Editor and Columnist

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — Featured Photo: Preventing the next pandemic by integrating human, animal and environmental health by Antonio Rota, 23 September 2021 Source: International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)