Fighting corruption, defending media freedom and human rights: these are the priorities indicated last week by Joe Biden in his opening speech at the Summit for Democracy, the virtual two-day event organized by the United States in which representatives of 111 countries were participating. As we all know by now, Biden has made the defense and promotion of democracy at home and abroad a cornerstone of his agenda; and he had pledged to host a summit for democracy in his first year in office, a promise now fulfilled.

From that standpoint, was this 2-day “summit” a success? Hardly. By universal agreement or almost – a rare consensus on the international scene – the summit was a resounding failure.

Why? Everything that could go wrong with it went wrong, starting with the way it was organized. Why would ever the United States a historic founder and supporter of internationalism and the United Nations decide to organize a “world summit” on such an urgent, complex, and yes, delicate matter as democracy without inviting the whole world, i.e. doing it outside of the international system?

One may well wonder whether it was a Trump legacy – a result of Trump’s gutting of the State Department – leaving American diplomacy rudderless. Because it is odd that a major power such as the US would go ahead with such a summit without making sure it had at least the backing of the UN Secretary-General.

And why not leverage the allyship with major European allies? Countries like the UK, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Austria, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Scandinavian countries or Greece could have been of great help. All of them are solid democracies committed to human rights – indeed, some of them are major, historic democracies with a better track record than the US itself.

IDEA, the Swedish think tank recently downgraded the US as a “backsliding democracy” creating waves in the media. The IDEA report concluded to the ‘visible deterioration’ in US civil liberties that had begun since at least 2019. In other words: with Trump. The report makes the point clear: “A historic turning point came in 2020-21 when former president Donald Trump questioned the legitimacy of the 2020 election results in the United States.”

One of the co-authors of the report, Alexander Hudson, clarified: “The United States is a high-performing democracy, and even improved its performance in indicators of impartial administration (corruption and predictable enforcement) in 2020. However, the declines in civil liberties and checks on government indicate that there are serious problems with the fundamentals of democracy.” A recent article on Impakter by a well-known American author and university professor, Annis Pratt, recognized the problem and ascribed it to the Republican party’s systematic strategy of “lying”, distorting the facts in order to gain and maintain dominance.

Perhaps the downgrading of American democracy on the international scene should come as no surprise, given the notorious Republican grab of the Supreme Court, turning it away from its fundamental role as the gatekeeper of American democracy – the function envisaged by the American founding fathers – into a machine to annul the results of elections and undermine democracy and human rights. The latest Supreme Court decisions regarding abortion are a poignant case in point – and could influence the mid-term elections. Another well-known one is the political incapacity of the US to address its gun problem and the consequent and unconscionable violence that extends to its children who kill each other in schools – the Michigan school shooting being the latest case.

In short, America does not present itself to the world as a credible champion of democracy – too many problems at home that need sorting out. I have no doubts that those problems will eventually be resolved but on a subject as democracy, America is not in the position to invite others and lecture to them, no matter how well-intentioned its President.

Let’s count the ways in which this “summit” failed. Starting with the invitations, exactly who was left out. Quite a few countries: Since the United Nations count 193 member countries, the “summit” left out 82 countries. The usual suspects were of course excluded: China and Russia. And as expected, they pushed back, accusing the US of exhibiting a “cold war mentality”.

More surprising was the exclusion of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, the only European country thus excluded even though the other members of the Visegrad group were not. Given their notorious illiberal policies, one wonders on what basis Poland, the Cech Republic and Slovakia attended.

For that matter, participants in the Summit included Angola, Iraq and the Republic of Congo, countries that the US organization Freedom House classifies as undemocratic. Also notably not invited, Turkey, even though it is a member of NATO, the Atlantic Alliance.

It is clear that the criteria for invitation were overridden by American likes and dislikes rather than dictated by a push for inclusion of as many countries as possible to discuss democracy.

The Impact on Europe: Not a useful result

Orbán explained his non-invitation with his close, personal ties to Trump. What is worse, though, is that he managed to prevent the president of the EU commission Ursula von der Leyen to intervene at the summit on behalf of the EU. This extraordinary result was obtained by taking advantage of the EU Council’s requirement that foreign affairs matters be subjected to unanimous approval of the 27 EU member countries – a requirement that effectively paralyzes the EU: It is enough for one EU member to voice dissent and any foreign affairs policy everyone clearly agrees on, like defending democracy, gets thrown in the bin.

In this case, Hungary expressed dissent and thus shackled the voice of the EU. This is, and not incidentally, the reason why EU diplomacy is so weak and muted and, as a result, the EU has, de facto, no voice on the international scene.

This – bringing to light yet again an EU weakness in its system – can hardly be termed a useful result either for the EU or the US.

The impact on the rest of the world: Confused and outdated?

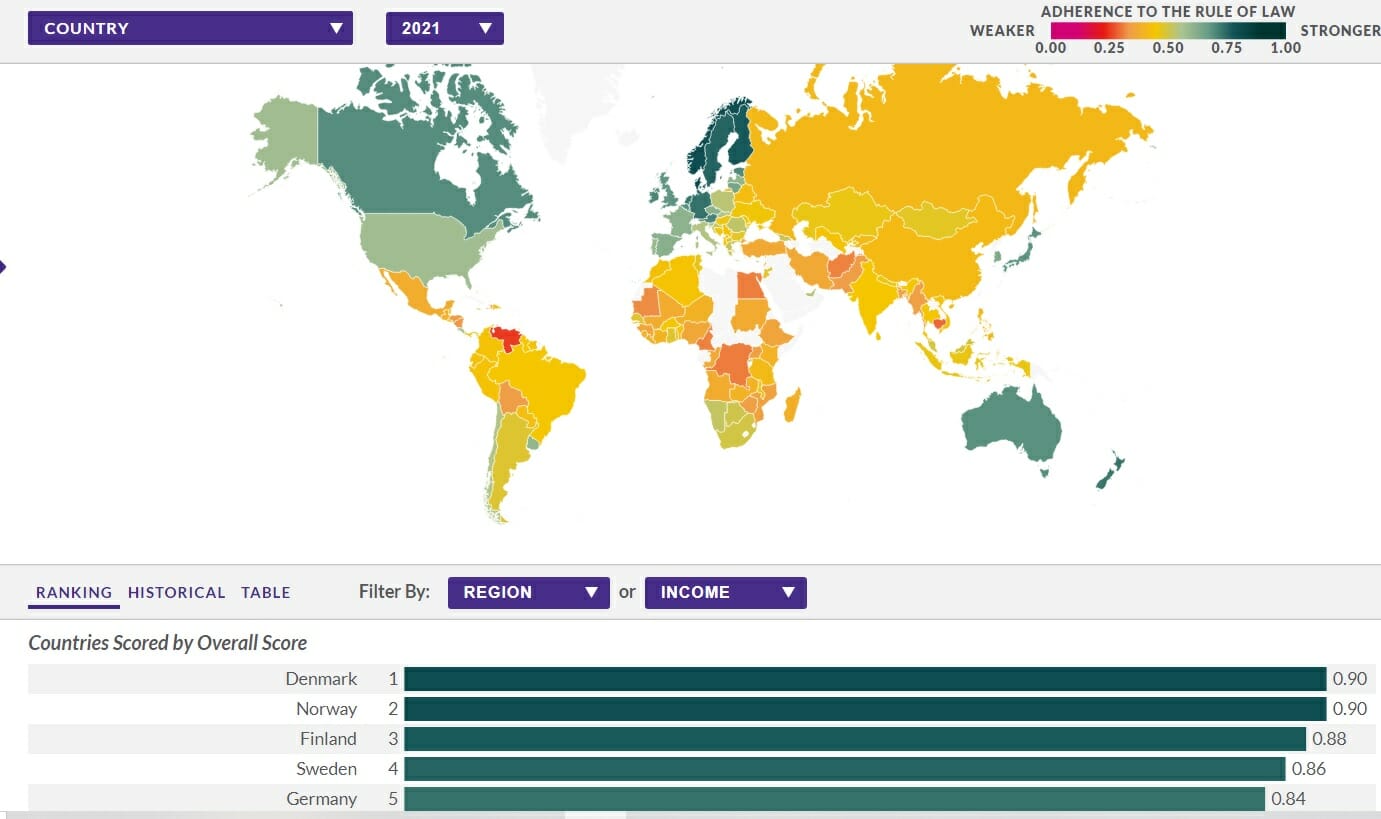

As the White House studiously avoided revealing on what basis countries were invited, a Brookings scholar, Ted Piccone, tried to assess the invitation list against the country rankings that are found in the World Justice Project (WJP)’s Rule of Law Index – presumably on the theory that the “summit” might have been conceived as an alliance of “like-minded” countries, a favorite of American diplomacy ever since President Bush launched his war against Iraq.

Briefly, Piccone’s analysis shows the following:

Latin America: Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay, top democratic performers on the index, were unsurprisingly included. The region’s two heavyweights, Mexico and Brazil, were borderline but made the cut. El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala were notably absent even though they are key countries in the migrant crisis the US is facing at its Mexico border.

Asia: The Philippines, although it ranks low on the index, was in together with Pakistan and India while Bangladesh was left out. Leaving Bangladesh out has to be defined as a big lost opportunity.

Africa: Only 17 countries were invited. Just as a point of reference: The UN lists 54 member countries in the Africa region. Several of the invitees are regarded as democratic standard-bearers, e.g. Ghana, Senegal, Botswana, Mauritius, Cabo Verde and Zambia. Traditional US partners like Liberia, Kenya and South Africa were also included. But countries that are experiencing difficulties and are barely or not at all democratic were also included: Niger, Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo and even Nigeria.

Among the more understandable exclusions were leaders from Mali, Guinea, Chad and Sudan, where in recent months military rulers have seized power unconstitutionally; Cote d’Ivoire, where President Alassane Ouattara circumvented constitutional term limits to secure a contentious third term; as well as Ethiopia embroiled in a bloody civil war and Egypt facing issues of human rights abuses. Yet, again, this begs the question: was this not yet another series of lost opportunities?

So, the verdict is in: The US clearly only invited its “friends” – or perhaps, the State Department’s definition of friends. But that’s a lot of excluded countries and a lot of excluded opportunities. Arguably, in this way, the US has publicly made known that it has a limited presence in certain parts of the world, especially Africa, leaving the impression that it has little interest in the continent.

Yet Africa could have offered the greatest opportunity for a real push for democracy. A recent poll across 34 African countries by Afrobarometer showed that large majorities support democracy and reject military rule, one-party domination and personal leadership. And that support remained strong for multiparty competition, parliamentary oversight of the executive and presidential term limits. African citizens also expressed high levels of discontent with the way democracy is working in their countries, thus polling for more democracy, not less.

Unfortunately, a view often heard in Africa is that the American approach to the continent is “confused and outdated”. Chidi Odinkalu, a professor of practice in international human rights law at Tufts University’s Fletcher School, argues that the summit was primarily about U.S. interests and priorities, and its guest list reflected that. There was little civil society input into the gathering, something others had noted earlier, calling for a more “democratized” democracy summit – something which now we know never happened.

So, as Odinkaly pointed out, America is facing a lingering distrust across Africa and much of the Global South over how sincere it is in its commitment to human rights and democracy. Its own democratic erosion doesn’t help, and many Africans are understandably hesitant. “The credibility of democracy in the U.S. is itself being tested to the limits with the outcome of the 2020 elections and its aftermath,” Odinkaly said. “More than how the U.S. can work with African civil society, the real question should be what kind of attitudes should the U.S. bring? A little more humility and introspection may be needed.”

In his speech, Biden announced a $ 424 million White House initiative for democratic renewal and human rights, including supporting media freedom. This is seen as “critical seed money” to launch “multilateral efforts” to defend and strengthen democracy and eliminate a range of obstacles, including “safe havens”, even online harassment. A commendably broad range of goals but certainly not a vast amount of money, still, better than nothing. Will that be enough to turn the tide of distrust and discontent? Only time will tell, but it is difficult to push off the feeling that it is not likely to be enough.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — Featured Photo: President Biden speaking at the Summit for Democracy Source: Screenshot from video of the full event’s first day, available here.