Editor’s Note: This article is part two of a two-part series by Impakter’s long-term contributor Dr. Festus K. Akinnifesi, Executive Coordinator of Multipartner Initiatives, Resource Mobilization and Private Partnerships Division (PSR) at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Previously FAO’s Chief of South-South Cooperation, Dr. Akinnifesi has over 30 years of experience in sustainable agriculture and food systems. In Part One (see here), major challenges in agriculture and food systems in Africa linked to the colonial legacy were identified and solutions proposed. Part Two explores the dilemma faced by the post-independence generation and elaborates on solutions.

The broad classification of generational gaps into the “Silent generation,” “Baby boomers,” “Gen Xers” and “Millennials,” among people born before, during or after World War II, has limited influence on agricultural development in Africa. The colonial heritage in Africa has proved far more influential.

In sub-Saharan Africa, three generations are notable, and have been classified in my previous article as (i) the pre-independence generation – people born during the colonial era (1942–1961); (ii) the quasi-independence generation – people born during the latter part of or just after the colonial era (1962–1981); and (iii) the post-independence (1982–2001) – people born well after the independence of most African nations. We will refer to these as pre-ind, quasi-ind and post-ind. This article highlights the challenges and prospects for reversing the influence of the colonial legacy on generational gaps to transform food and agriculture systems in Africa.

Generational gaps status and agri-food systems

The pre-ind are the loyal farmers since the colonial era, but are now ageing. Many of the pre-ind are locked into a poverty trap. The quasi-ind are strongly influenced by their colonial heritage on agriculture and food systems. Unlike the preceding generation, the quasi-ind saw education as an escape route out of poverty for their offspring. There is little incentive for quasi-ind to retire to agri-food systems at an advanced age.

On the other hand, the post–ind generation faces a dilemma. Although the majority of youth between 15 and 35, which constitute 35% of total population, live in rural areas, agriculture is not attractive to them. Although they are generally more educated, they have little interest to embrace agriculture as a viable career path. The post-ind generation sees agriculture as a nuisance and perhaps a poverty-perpetuating venture.

More crucially, the post-ind often inherit few or no assets or farming skills from previous generations to support productive agriculture. This places an excessive burden on the pre-ind, who produce much of the continent’s food, and are ageing. All these at times complex and conflicting factors must be addressed in order to transform Africa’s agri-food system. More than ever, Africa needs its young people to transform agriculture and food systems sectors.

Restoration of Africa’s food self-sufficiency

Africa’s agriculture and food systems face a nuanced generational challenge. Its colonial legacy of sole emphasis on cash crops for export markets and inadequate investment in agriculture and food systems development have contributed to poverty, and the negative mindset of the post-ind generation towards farming. This legacy takes the form of “path determination,” implying that colonial choices determined post-colonial policies and political systems, or at least conditioned them. After their independence, most African countries largely retained colonial legislation, such that departure from them became, and perhaps remains, difficult and costly.

The pre-colonization Africa’s economies were self-sufficient in food production. Later, a commercial, non-food, monetary and export-driven economy was prioritized, which replaced the agricultural food economy. In the process, the agri-food systems, including agricultural land-use, production and markets, shifted from subsistence farming to cash crops for export, at the expense of domestic self-sufficiency in food production.

Related Articles: Flexible Pooled Funding Mechanisms Can Drive Transformative Change | The secret recipe for scaling climate-smart agriculture: Youth

The persistent food deficit in the continent can be chalked up to its colonial policy legacy — which promoted a shift to cash-crops and monoculture. In Eastern and Southern Africa, the axiom was “maize for food” and “tobacco for cash” — both were new crops introduced to the continent. Likewise, tea, coffee, cotton and tobacco were also promoted for cash, mainly exports.

Tobacco was and still is touted as “green gold.” In West Africa, cocoa, oil palm, rubber and cotton were promoted for export and cash, with cocoa touted as the “money tree.”

The resulting intensification of cash crops and mono-cropping drove many native crops and food-producing tree species to extinction. It also resulted in the fragmentation of forest lands and cultivation of crops on marginal lands.

Government policies and support were increasingly geared to mainly cash crops, including the systemic allocation of subsidies, credit, inputs, extension services and markets. Food production for domestic consumption became secondary. Farmers had (and continue) to sell their cash crops to buy food, and the door to food importation widened.

The loss of food self-sufficiency — moving up in the value chain

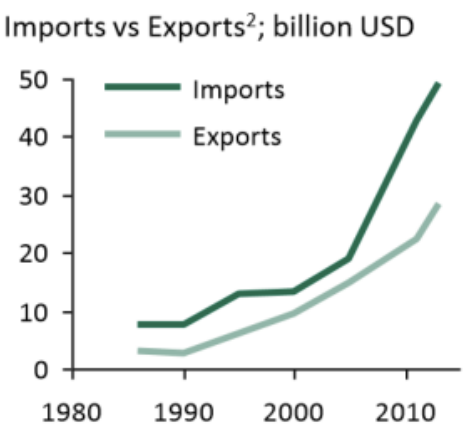

In the mid-1970s and early 1980s, Africa became a net importer of food and agricultural products. This coincided with a period of falling prices of commodity crops. Africa spends US$35 billion annually on importing food, which is projected to increase to over US$110 billion per year by 2025. This loss of food self-sufficiency and importation also translates to indirect exports of jobs out of the continent.

Historically, African farmers have always been price-takers. As a result, they have continued to be vulnerable to the vagaries of domestic and international market gluts and fluctuations. This is largely due to the lack of alternative domestic use for their non-edible harvests and export crops. More land devoted to cash crops farming also translates to less arable land available to grow food crops, more deforestation and loss of biodiversity.

African countries as top producers of some cash crops, so what?

Going forward, Africa should follow the lead of other continents and produce what it consumes, and eat what it produces. Many African countries are top producers of cash crops for export, yet the continent is a net importer of food, despite having a large diversity of native, neglected and underutilized nutritious food crops, including the so-called “orphan crops.”

For instance, Kenya has ranked in the top three-five world producers of tea for over a decade, and has ranked third in 2020. Smallholders in Kenya produce about 60% of the tea on farms of less than one acre. Despite relatively good returns, it does not translate into economic wellbeing of smallholder farmers due to limited economies of scale. Other notable tea producing countries in Africa include Malawi, Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda.

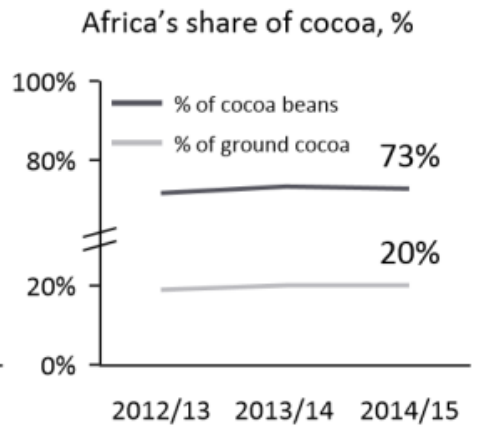

Four of the top five largest cocoa producers in the world are in Africa — Cote D’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria and Cameroon. Despite accounting for 70% of world cocoa production, an average cocoa family farmer in Africa earns less than US$ 1 a day. This is below the poverty line!

In recent times, tobacco production has shifted from high-income to low-income countries. In 2020, despite the devastation wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic, five African countries were still among the top 20 tobacco leaf producers, with Zimbabwe ranking as 4th, Zambia 7th, Mozambique 12th, Malawi 13th and Uganda 20th. However, the local farmers and labourers remain poor.

Paradoxically, data by WHO shows that Africa has the lowest rate of tobacco use compared to other continents. As high-income economies move away from tobacco, African policymakers must incentivize farmers to diversify production systems back to food crops primarily for domestic consumption and continental market.

Most of the crops produced and exported are raw material for industries. Africa needs to effectively participate in the value chain beyond the supply of raw materials. The continent’s policy incentives need to move Africa’s participation up the value chain. This will also act as a crucial incentive to attract the post-ind to agri-food systems.

Distortion of food systems and indigenous food culture

Africa’s agriculture and food systems are a mismatch with its richness and vast natural resource endowment. Colonial and post-colonial food production has focused on commercial, non-food security crops and less nutritious staple food crops, a prioritization that has been reinforced by successive government policies, investment programmes, extension support and inputs-delivery systems.

This situation is a result of decades of policy bias that have promoted or even in some cases, mandated cash crops at the expense of food production for local consumption. Cash crops also generally rely on the use of fossil energy and synthetic chemical fertilizer, herbicides and pesticides, which deplete the natural resource base.

The indigenous food culture has almost disappeared in some African countries that experienced delayed independence. Intensification of monoculture has led to a loss of food and nutrition diversity with minimal investment in crop improvement, diversification and biodiversity conservation. The value chain is short and the return to labour is low for the cultivated cash crops. The domestic market focuses on primary production of starchy staples.

Africa’s agriculture needs to move from crops that provide simple dietary energy to more biodiverse and nutritious food. This will ensure nutrition-based food security and stimulate job creation along the value chain.

The post-ind are more accustomed to monocrops, imported and/or “industrial diets,” and fast-food menus laden with excessive amounts of fat, sugar and salts, and animal-sourced foods. The rising levels of obesity in Africa are now becoming worrisome, particularly as there is a close link between obesity and the rise in non-communicable diseases.

A New Era of Opportunities in Africa

Until now, it has been an uphill task to get Africa’s agriculture and food systems onto a sustainable path. Attaining zero hunger, nutrition and sustainable agriculture is still a formidable challenge. The debilitating impacts of environmental degradation and natural resources depletion or threats are mounting. Infrastructure in Africa is inadequate and represents another disincentive to the post-ind.

Rethinking generational gap dividends and addressing them in policy decisions is crucial to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and Agenda 2030. Africa must no longer wait to harness its huge potential and unique assets: its vast natural resources, huge youth population, surplus labour supply, and large domestic food market.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) presents an era-defining opportunity to remove national barriers to continental trade. Intra-Africa’s continental market for food crops is huge.

Africa must also leverage the youth’s zeal and aptitude for innovation while promoting broader partnerships, south-south and triangular cooperation. According to AGRA, the food market in Africa is huge and has been projected to reach US$ 1 trillion by 2030. If well harnessed, this can create decent jobs for the youth, empower women and improve livelihoods.

Invest in sustainable agro-industries

Developing sustainable agro-industries and re-orienting school curricula toward agri-entrepreneurship is a precursor for attracting the post-ind into food production to meet domestic and continental demand. This investment will create much-needed jobs.

In addition, rather than exporting agricultural primary products as raw material for industries, focusing on exporting secondary primary products is the future for the post-ind. This requires good quality assurance and value addition.

Re-directing the interest of post-ind to food production and the market value chain is key. Restoring Africa’s “orphan crops” or “lost food crops,” improving them, and retaining their intellectual property is a priority. Deliberate efforts to develop and promote Africa’s traditional indigenous cuisines from its native crops is long overdue.

Access to knowledge, technology and digital innovation

Hope lies in digital innovation and technologies, which could transform Africa’s agriculture and food systems. But the uptake and prospects depend primarily on educational levels of the population, which varies between generations as well as countries.

On the positive side, there has been an upward trend in intergenerational mobility in educational attainment across African countries. The post-ind are generally more educated than previous generations. This upward educational mobility has implications for the continent’s skills-set, labour markets and technology adoption.

Majority of pre-ind have limitations in adopting modern technologies and innovations. In general, the pre-ind are “outsiders” to digital innovation. A small proportion of quasi-ind are amenable to technology, while the post-ind are more tech savvy. The majority of quasi-ind are generally known as “digital immigrants.” This is because digital technology is their “second language,” requiring ample efforts to master it, whereas the post-ind are “digital citizens” and are more open to digital innovations and solutions.

The current wave of digital revolution in Africa is a socially disruptive phenomenon, but if harnessed and applied thoughtfully, it can be a game changer. There is need for targeted policy incentives to expand access to capacity, digital innovation, infrastructure and markets. Technology has the potential to open up new opportunities and new markets, but the success of digital inclusion depends on identifying needs and bridging generational gaps. This includes gaps in the capacity, skills and use of digital innovation.

Access to productive resources

With Africa’s burgeoning youth population, the provision of decent jobs is urgent and crucial. To make agriculture and food systems appealing, investment in constructing and upgrading modern infrastructure is critical. This includes rural roads, transport system, irrigation, ICT, mechanization, energy and market infrastructures. Technologies and innovation must be labour-saving, gender-sensitive and youth-friendly. Land tenure is a major problem in Africa. Of approximately 51 million farms in Africa, 80% (or 41 million) are smaller than two ha in size. Access to land, irrigation and other productive resources is fundamental for transforming Africa’s agriculture. Policies that address land tenure and increased access for young farmers are important.

Looking forward

There is growing optimism for Africa’s transformation in the next decade. Bridging intergenerational gaps can leverage skills, knowledge and resources to transform food systems, providing untold benefits. Harnessing the potential of intergenerational dividends requires a shift in mindset. Currently, a favourable set of conditions can accelerate Africa’s agriculture and food systems transformation.

First is a tech-savvy youth population coupled with a cheap labour supply. Second, the prospect of diversification to nutritious food systems; this includes improving Africa’s orphan or “lost food crops” and indigenous diets. Third, there is need to harness the benefits of Africa’s intercontinental free markets. Fourth, scaling up connectivity and digital innovation can transform Africa’s agriculture. Government policies must focus on making agriculture more attractive for the young generation, including policies that focus on upgrading and transforming infrastructure. Fifth, after decades of feeding the continent, the ageing farming population in Africa also deserves attention. Social protection and insurance schemes are important for the pre– and quasi ind farmers and agri-food systems actors.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Featured Photo Credit: ©FAO.