As negotiations continue at COP26, greater clarity is provided as to which country is ready to concede the most in order to halt and reverse human-induced climate change. Yesterday the focus was on energy, phasing-out coal, and ensuring a global just transition.

To meet the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreements in limiting global temperature rises to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the global transition to clean power must progress four to six times faster than at present. The UN Environmental Programme (UNEP) also announced that poorer countries will need five to ten times more money to adapt to the consequences of climate change than they are currently getting.

The plethora of statements announced, agreements signed, and finance figures thrown around, has demonstrated that world leaders are keen to show their readiness to reach net zero by 2050, and abide by the Paris Agreement.

This is exactly what Boris Johnson, and the Conservative Party have been seeking for in hosting the Climate Summit in 2021. The calculated pragmatism that is behind the Conservative Party’s green agenda has never been more obvious. The UK is hoping to become an exemplary model for green transition, and reinstate itself as an important world player, seeing COP26 as a test for its “post-Brexit” diplomacy.

Yet, these “optimistic” commitments and pledges have been nothing but mere window dressing – hiding the enduring conflict and distrust between developed and developing countries, as well as the unwillingness from most parties to phase out coal appropriately.

The deal to phase-out coal …

On Thursday, the UK announced that 190 countries and non-state actors, have now committed to the Global Coal to Clean Power Transition Statement (GCCPTS). Each country (46) has varying phase-out dates to transition away from unabated coal power generation, but rich nations must do so in the 2030s, whilst the rest of the world have until the late 2040s.

This agreement came alongside an announcement by the Powering Past Coal Alliance, declaring a total of $17 trillion in assets to be directed towards stepping away from coal towards clean power. It includes major international banks such as HSBC, Fidelity International, and Ethos, which have all committed to end all international public financing of new power plants.

“From the start of the UK’s Presidency, we have been clear that COP26 must be the COP that consigns coal to history. With these ambitious commitments we are seeing today, the end of coal power is now within sight.”

– COP26 President, Alok Sharma

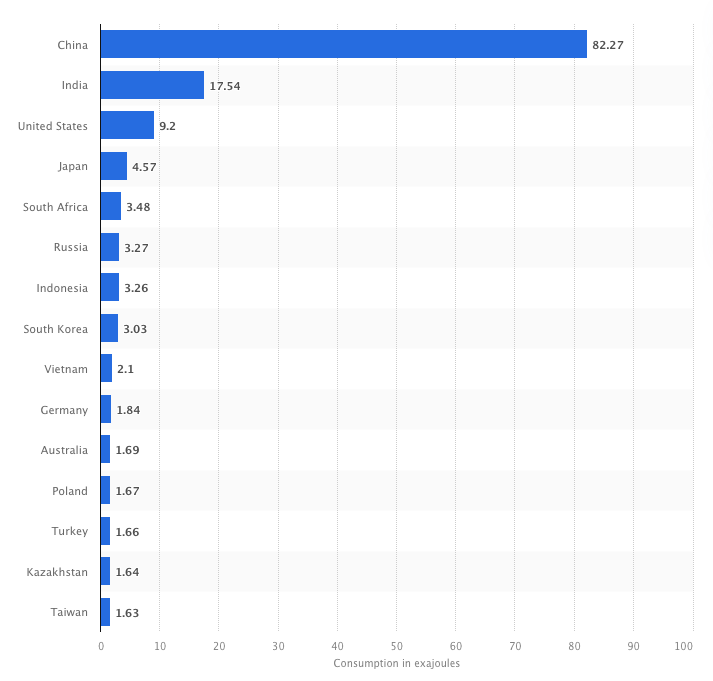

A momentary celebration cut short as the UK failed to win support from China nor India – top two global coal consumers. The chart below demonstrates that China consumed 82.27 exajoules of coal in 2020, which approximately equates to 54.3% of the global coal consumption, whilst India used 11.6%.

Furthermore, a UK negotiator announced the statement was deliberately flexible in its conditions and clauses, to leave ample space for signatories to sign without having to make too many concessions right away.

Poland, for example, signed the pledge but the Climate ministry in Warsaw said it would not phase out coal until 2040s, the same timescale it was already planning.

Indonesia, whilst agreeing to the first two clauses on scaling up clean energy and to power down coal, refused to back the clause calling for an end to building and financing new unabated coal. This is not surprising considering Indonesia is the number one coal exporter.

It would, however, consider accelerating phase out into the 2040s, only if there is additional international financing to do so.

Climate Financing

Additional international financing has also been demanded by the African Group of negotiators on Climate Change (AGN) which called for developed countries to provide $1.3 trillion per year from 2025 to make green transition feasible within the African continent. In addition, they called for governments grants to ensure African nations avoid any further indebtedness in the process of phasing out from coal.

The AGN chair Tanguy Gahouma-Bekale, has also called for a 5% fee on the proceeds from trading all types of carbon credits. This, he believes, could unleash $1 trillion of new capital investment towards developing countries, help reduce emissions, and encourage technological innovation. But, the European Union only accepts this sort of transaction tax in the case of offset trading between public and private players, and not for the exchange of carbon between countries.

“We, with other market participants, are not prepared to accept any kind of mandatory extension…so, what we’re trying to provide instead of that mandatory international tax is more reassurance that the EU is committed to scaling up adaptation finance.”

– said Jacob Werksman, EU negotiator, at COP26

The EU prefers to resort to alternative mechanisms that don’t involve a levy on its own internal market and instead provide direct aid funding to the developing world to assist it in its energy transition. Whether it will do so of course remains to be seen, and whether it will be enough is a matter for discussion.

More generally, the developed world prefers to channel climate finance through funds. India, Indonesia, and the Philippines have joined South Africa, on Thursday, to become the first recipients of one of these – the Climate Investment Funds – which would accelerate their transition away from coal power. The programme is endorsed by the G7, and supported by financial pledges from the US, Britain, Germany, Canada, and Denmark – adding up to about $2 billion.

The EU, along with the US and the UK have set up a separate Partnership dedicated to South Africa to ensure a just transition – South Africa Just Energy Partnership – worth $8.5 billion. This could set new precedents for supported transition in other high-emitting coal-using countries, such as Indonesia.

In the meantime, Indonesia will not consider phasing out coal. Developed countries must assure that they can deliver sufficient funds to enable the acceleration of the transition away from coal towards renewable energy in developing countries. Many will restrain from fully committing to any of these pledges until richer nations take responsibility for having the greatest historical accumulative carbon dioxide emissions.

Related Articles: As Coal’s Power Dwindles, Renewables Set To Come Out on Top | COP26: Can Rhetoric be Transformed into Action? | G20, the Club of Richest Nations, Disappoints On Climate Change

Another major point of contention is the urgent call for loss and damage support from climate-vulnerable countries – something that developed countries, starting with the United States, will not consider. It would arguably open an endless debate similar to the one that was started over slavery or World War II reparations and most developed countries are exceedingly reluctant to open that particular Pandora box.

To regain trust, the developed world will also need to delineate clear national plans on how they hope to channel private investment in green projects towards high-risk poor nations.

Carney’s $130 trillion in Climate Finance Commitment is immense and positive but drew scepticism from non-governmental organisations and activists. The several asset managers that signed up to Carney’s commitment had so far aligned just 35% of their total assets to net zero targets. The figure of $130 trillion of assets is said to not be “aligned with net zero today” but that “the ambition [was] for the assets to be aligned” in the future, said founder of the financial think-tank Carbon Tracker Initiative.

Developed countries are not ready to back down

Alok Sharma told a news conference it had been a personal priority as COP26 president to consign coal to history and, he added, “I think you can say with confidence that coal is no longer king.”

Coal may no longer be king, but COP26 did not single-handedly change this – and it has been the work of many people working over time in both the private and public sector. However, we are clearly not there yet: Greater efforts must be taken in order to seriously consign coal to history today, not tomorrow, not in the 2030s, and even less so in the 2040s.

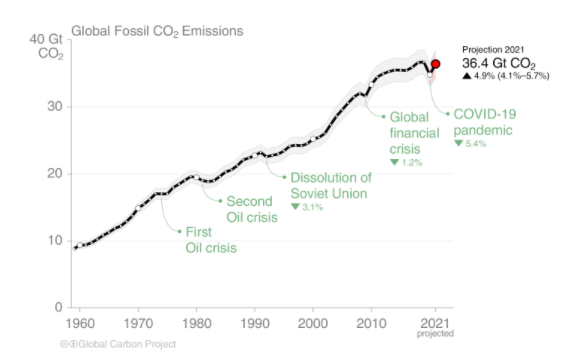

A recent study has announced that carbon dioxide levels have returned to near pre-pandemic levels. If COP26 wants to maintain the Paris Agreement of limiting global temperature to rise above 1.5 degrees Celsius pre-industrial levels within reach, then we must halt business-as-usual and delays are no longer acceptable.

Many developing countries rely on cheap, accessible coal to fuel their economies. Beyond the environmental and public health cost, on a short-term financial standpoint they do not have much incentive to turn away from coal. Although solar powered energy has now become the cheapest electricity in history, the diversion from already operating and constructed power plants towards new renewable energy infrastructure is unfeasible and costly.

Developed countries must take greater responsibility and accountability for having the greatest accumulative worldwide CO2 emissions. They must appear credible amongst leaders, in reminding themselves that they have undergone their own industrial revolution, which severely impacted developing countries. Today, these same countries cannot demand for global coal phase-out without funding the transition in a just and supervised manner.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Construction of a Coal power plant. Featured Photo Credit: Shane McLendon.